(This article is part 3 of a series called “The Blessings of Babel.” The first part of the series can be found here, and the second part can be found here.)

Writing the final installment of my series on modern literacy, I realize that the reader might now be lost among my various digressions.

Through this multi-part essay, I examined the decline of literacy and the various forces that have trapped the modern imagination. In part one, I observed the modern decline of book culture and traced its source back to the loss of the spiritual telos of the Divine Word, which literature was meant to pursue. In the second installment, I approached the problem from a different direction, postulating that modern illiteracy itself might be a natural adaptation designed to overcome the unbounded flow of hazardous information traps common to late-stage civilizations. To this point, I hope to have painted a picture of the dual forces that paralyze modern Western culture: a crippling fear of past corruption combined with the stifling despair of spiritual absence.

If a reader has followed me thus far, we might conclude that modern civilization now necessarily exists in a state of intentional cultural illiteracy. Moreover, to the extent that any of us want to “escape the slop” of modernity and find a culture of genuine sincerity and heart, we must move away from the mainstream and seek meaning within different communities that have a stronger connection to a core spiritual vision.

Such are my conclusions, not succinctly made across the first two essays. And I wouldn’t blame any reader for feeling frustrated.

After all, I haven’t proposed any specific solutions to the problems I examined. And aside from just walking away from mainstream culture (which we are all doing anyway because it’s terrible), there is no clear path to better alternatives. Anyone not already integrated into an Anabaptist community or living in a monastery still has to understand their culture within the context of the modern mainstream. We all want a certain amount of separation and a new perception of meaning, but it’s not immediately clear what that would entail.

Still, we have to start somewhere.

Speaking as a somewhat “cultured” person, I begin with the books that have given my life meaning over the years. Here, lying among the various titles that I have collected, a different perspective comes into focus. Each entry on the shelf isn't there because it met some objective standard of goodness, but because it represents a thread within my own life. Each book marks a type of thought that answered questions and opened doors, connecting me to the people of the past who struggled with similar problems, and linking me to many others in the future who will use its symbolic language to understand the world.

The sections of the bookshelf are the spreading branches of a tree, reaching out, bending, and turning with the changes in spirit. Some branches were fruitful and led to new avenues of development. Others were poisonous and required pruning. The pattern of my exploration in the world of letters was disjointed and not something that might be replicated by a canonical syllabus.

The experience of literacy is organic on the personal and societal levels. Thought is a living thing. It requires cultivation rather than engineering. Moreover, as much as I would like to go back and “unmake” the intellectual mistakes of my youth, my appreciation of literature needed to grow in the mulch of error and towards a desire for good things, discovered through lived experience. Such development could not be controlled by technique, even if it might be otherwise guided by mentorship and education.

I recall this fact every time I see another article from the mainstream chastising men for not appreciating books anymore.

Men won't dedicate time to reading a book unless they feel that a book is important to their lives and higher ambitions. Moreover, these feelings of importance can't be demanded as a function of a procedure but must grow naturally out of a person’s understanding of spiritual purpose.

Given that our intellectual class doesn’t believe that young men have much use, to begin with, it shouldn’t be any surprise that those young men don’t read their critically acclaimed novels. They would have more luck if they went home and lectured their rose bushes on why they should be red rather than white.

In a similar way, I often encounter a common misperception from younger men who request a list of essential 'must-read' books. I understand that the young men asking this question are seeking mentorship and a clear path to intellectual development. But such a question isn’t well-posed, generally.

What does "Must read" even mean outside of the context of a time in life?

Certainly, after talking to a person for a few moments, one can get a sense of the type of questions they are asking and the specific set of books that they might be ready to pick up. However, there is really no essential list of texts for a “general person.”

Books are highly personal things, and people go through stages of learning. While I take pride in my ability to “read the man” and understand which book might benefit him in a moment, It would be useless to give Crime and Punishment to a guy who wasn’t ready to explore profound questions about morality, just as it would be insulting to give someone Conan the Barbarian if they were in a mode of spiritual seeking.

Blasting out general book recommendations on the internet is never really productive; it's like a horticulturist giving general recommendations on what flowers to plant without knowing the season and location in which their readers are gardening.

I know which books have historically been impactful and those that influenced great men of the past. However, saying that a book was “important” would imply that I completely understood the work in an absolute sense when my understanding is entirely bound to a specific moment in history and my own life.

How many times have I read a book, dismissed its message entirely, only to revisit it later to discover some deep theme that I never imagined?

Many times, certainly.

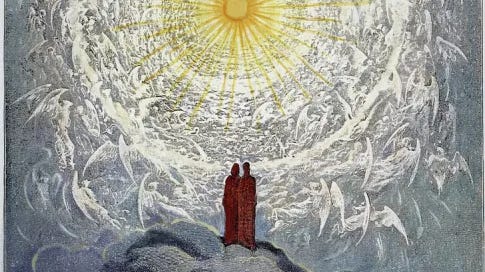

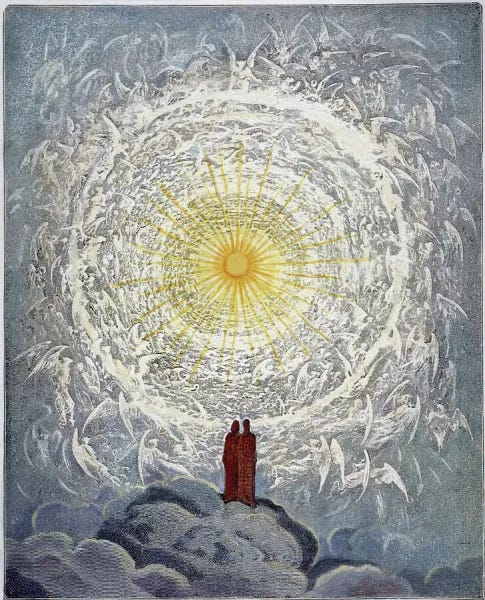

And that’s not to mention the books that I feel had a significant impact on my life, but still can’t quite express their meaning in words. For myself, Moby Dick, every German idealist philosopher, and quite a few early 20th-century “realist” authors fall into this category. In fact, even when it comes to my favorite epic poem, Dante’s Divine Comedy (a work that I frequently reference), I am still very hard-pressed to explain why this book is worth reading.

But this difficulty doesn’t seem to be a personal failing. I am not alone in having difficulty expressing the meaning of this poem describing the Florentine poet’s travels from Hell to Heaven on the eve of Good Friday, 1300 AD. Naturally, any teenager (or Reddit commenter) will chalk The Divine Comedy up to a giant exercise in psychological projection, a cosmic revenge fantasy. And I suppose James Burnham’s association of Dante’s political vision with over-idealization means that the accusation of being a “wish-fulfillment fantasy” will forever haunt the Tuscan poet’s work, even among intellectuals.

Nevertheless, most thoughtful people who make their way through Dante’s medieval masterpiece feel that something of true intellectual and spiritual gravity is being revealed, even if they do not share Dante’s politics or religious perspective.

There is something evocative and numinous in the symbolism that the poet employs, and that can be felt in the beauty of his verse, even through its translation from Italian. Still, the ultimate source of the poem’s importance, both historically and spiritually, seemed mysterious to me, at least until recently.

The most common explanation of Dante’s timeless appeal that I regularly heard was that his epic had “constructed a Christian Cosmos.” Still, that seemed like an excuse. After all, ordinary medieval people must have understood their own cosmic conception of the world, spun together from the union of Christianity and the remnants of ancient paganism. Any educated man of the era could have constructed his own visions of Heaven and Hell based on the contemporary common sense of the time and his own political preferences.

The appeal of Dante’s Comedy seemed a mystery, but a part of the puzzle fell into place when reading Carlyle’s On Hero Worship, where the author proclaimed that “Dante shall be invaluable, or of no value (at all).” With any other author, such a phrase might be dismissed as a rhetorical flourish, but with Carlyle, it never is. The Divine Comedy must mean everything or nothing at all. That is the nature of the poem.

But what kind of document has such an all-or-nothing quality to it, being either of supreme importance or no importance?

Perhaps a map?

A map is useful, provided that you are lost in the area that it describes. In fact, if you are lost, a map is pretty much the only thing worth looking at. It is invaluable until the moment that you step out of the region that it describes, and then you are lost again, and your map will no longer help.

To borrow an insight from Walker Percy, perhaps The Divine Comedy was the tool that helped medieval man when he was lost in the cosmos.

But how can an entire civilization be lost?

The thinking man of the Middle Ages certainly knew where he stood, cosmically speaking (an advantage he held over his modern counterpart). But everything outside of his time and moment seemed irrecoverably distant. The past, while legible, was separated by a chasm of religion and time that cleaved the early Christian from his classical predecessor. And, while the ancient world certainly influenced the Middle Ages through the legacy of Platonism and the work of scholars such as Thomas Aquinas, the integration of ancient thinking into the medieval zeitgeist was very much an exercise in archaeology. The thinkers of pagan Europe were as alien to the Christian imagination as the luminaries of the Muslim world. It took another step for the Christian world to view the past as something that could be interacted with, both intellectually and spiritually, thereby laying the groundwork for the Renaissance.

It is in accomplishing this critical connection that the poetry of Dante Alighieri made its true mark on the European consciousness.

Whatever the reason, anthropologically, man’s relationship to a text must always be personal to be intellectually real. We might proclaim the “death of the author,” and indeed, most authors are deceased. But a book cannot be a book unless it is conceptualized as an interpersonal dialogue with the person who wrote it, even if that author has been buried in the earth for a thousand years.

If we cannot understand a book as the product of another person’s struggles with life’s problems, we aren’t so much reading as we are deciphering runes, assembling a hieroglyphic puzzle with little correspondence to our lived reality. If you cannot understand the life or value system operating on the other side of the text, it loses its dialectical quality and becomes a dead letter.

As many have speculated, it is precisely such spiritual separation and cultural illiteracy over time that, perhaps inevitably, cause the death of one civilization and the emergence of a new one. Even if two successive people are born from the same gene pool and raised on the same land, the separation of spirit remains because the disconnect in moral language creates too vast a gulf for intergenerational understanding to cross.

Call it Spengler’s civilizational winter, Fortuna’s downward turn, or “The Blessings of Babel,” but at some point, people exit from the map that was created by their ancestors and can only look backward vaguely to what came before, the past hidden necessarily for “There be dragons.”

But after Winter, there is spring, a revivification, and perhaps even a Renaissance. And the Tuscan poet’s Divine Comedy holds the key.

Through the portal of his Cantos, via a historical record written in verse, Dante gave the medieval world its new moral map of the universe and its ability to understand the civilization that bequeathed it. Stretching from the deepest circles of hell to the highest sphere of heaven just above the seven-story mountain, Dante’s journey across the cosmos restored the moral dimension of thought, and the world, both ancient and medieval, became discernible. Those souls whose Dante’s light touches are transformed from being distant and half-forgotten voices to real human persons, ready for conversation.

Here at once were Brutus, Alexander, and Odysseus, not as pagan artifacts but as real spirits struggling with their own triumphs and failures, ready to tell their own stories.

There again were Cato, Statius, and Virgil, not as distant memories but as paragons of the old world’s hope, a prefiguration of the Christian promise.

And there, ever upwards, were the Saints. Peter, Francis, Beatrice, and the Lady who represented humanity’s ultimate aspiration.

Dante had taken a single beam of light, shining across the darkness of the Middle Ages, and had refracted it, like a prism, into the many colors of the rainbow, scattering it outward to illuminate a new universe waiting to be explored and uplifted.

The stories of old were now brought to life and woven into the context of a living tapestry. The goodness and badness of the old world now was rendered lucid and linked to a common telos, winding upwards slowly from iniquity in the Inferno, to redemption in Purgatorio, to its final end in Paradiso. Dante’s ultimate Canto unfolds like spring, revealing a new eternal destination, combining and transcending the futility of Fortuna’s wheel and the grimness of the Christian apocalypse. In the Empyrean, medieval man found his aspiration in the limitless Divinity that Dante witnessed standing behind the Virgin Mary, the infinite horizon beyond all horizons. And it was at the feet of the Queen of heaven that Faustian man was born, perhaps reborn.

I begin my search for cultural remedies with Dante, not because I believe we are about to receive a new transformative epic like The Divine Comedy in our time, but rather because I think that Dante’s perspective provides a framework for understanding what a civilizational rebirth looks like and the necessary methodology for restoration.

The methodology for restoration lies in developing a new language that magnifies the wholesome elements of life, imbuing them with a sense of sacredness while rendering poisonous concepts profane and inaccessible. Language is never really language. The word that is announced in reverence will eventually be worshiped. The ideas that are ruinous cannot be spoken of without some amount of harm.

“Speak the name of God in a spirit of prayer, and He will provide. Speak the name of the Devil, and he will appear.”

Thus, the beginning of piety is born in the regulation of symbolic speech, which in turn is always derived from a deeper and harder-to-describe understanding of poetry and faith.

Ancient and medieval people implicitly felt the connection of language to morality, but in modern literature, such an understanding is somewhat rare, even though we find a notable exception in J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings.

Fans of Peter Jackson’s adaptation often overlook this critical dimension of the trilogy, but Tolkien’s epic is as much a vision of history and poetry as it is an adventure story. It is in the slow, plodding chapters that a reader gets a glimpse of the spiritual and mythological world that Tolkien is trying to create. Within the breaks of poetry, the recounting of legend, and the moments of mystery, the author’s vision of Middle Earth comes into focus, not as the stage for an epic but as a mirrored vision of our own fallen world.

Tolkien wanted to tell a story about a land and its people, but one can’t really tell a people’s story without first describing their history, geography, and poetry; hence the voluminous appendices, maps, family trees, extended books of history, and the author’s development of new languages.

On this last point, two peoples emerge in diametric opposition, the Elves and Orcs, each with their own language. The Eldar have their Elven Runes. The denizens of Mordor have the Black Speech. The two languages are similar in form but spiritually opposite. The Black Speech is a form of Elvish; it looks the same in writing, and it comes from the same place. But its uses are entirely different. Elvish is the language that all people use when singing their songs, writing their poetry, and creating sacred artifacts. The Black Speech is used only intelligibly in conspiracy and battle; it appears in writing only in the form of curses, the most prominent being the curse inscribed on Morgoth’s ring.

J.R.R. Tolkien understood that a people’s language defined their connection to the past and, therefore, their link to the future. This connection is only logical. A people’s language is their map of meaning. It defines their understanding of the sacred. And if that language becomes profane, the people will lose their ability to understand their purpose, collectively.

Fundamentally, this linguistic issue plagues the Millennial generation’s frequent, yet futile, attempts to find meaning in their lives. People say that our generation is “irony-poisoned”. But really, we are “profanity-poisoned”. Cynicism is baked into our language, and therefore, how we think about our identity and the future.

Dudley Newright pointed to this problem in his essay about “Millennial Snot.” As the author outlines extensively, modern Millennial speech is infested with juvenile cliches borrowed from drag queen camp and other urban sub-cultures that inevitably lead to many professors, intellectuals, and elite mainstream journalists talking like a cadre of teenage girls. Within this mode of communication, many Millennials have become incapable of clear, straightforward communication and prefer instead to express themselves in profanity-laden self-affirming irony at all times, aka “Millennial Snot.”

Dudley New Right’s insight was on the mark. However, I think his analysis didn’t go far enough. As irritating as it is to deal with bad writing and banal mid-wit opinions in the context of “Millennial Snot”, the real fallout is the fact that this type of language can’t be used to express an idea of the sacred and numinous. It is a means of communication that is thoroughly profane, able to express contempt and condescension but never a spirit of poetry. That’s why it relies on using literal profanity like “F*CK” so frequently.

And has enough been said about the Millennial over-use of that infamous “F-Word”?

As much as I have been harmed by the various information hazards of modernity, from pornography to the dopamine traps of the internet, few have had as negative of an impact on my development as the word “F*CK.” It's amusing to look back on my youth when I heard warnings about profanity, especially the “F-WORD,” because these warnings never seemed to make any sense. The distaste over “coarse language” appeared to be the most arbitrary piety of older generations. After all, “F*CK” was just a word! People in the past simply decided that this combination of syllables was bad, and now we have to follow suit. How did that make any sense? The word was fun to say. And its negative connotations would eventually fade as the word was used more and therefore robbed of its impact. Eventually, we would just have a version of the English language that didn’t contain words considered profane, and wouldn’t that be better? After all, weren’t “Hell” and “Damn” once considered deplorable language? And now, people didn’t even care about Hell or Damnation.

That was progress, wasn’t it?

What was not then apparent to me, or to any of my cohort at the time, was just how insidious such use of profanity was. “F*Ck” wasn’t just a word; it was an incantation; it was taking something sacred to the human condition and characterizing it as an aggressive bodily function. Moreover, its effect didn’t wear out over time (as we assumed it would) but instead began to colonize the rest of our vocabulary. No matter how many times it was used, the word robbed attention away from more solemn things and redirected it towards ostentatious acts of ironic desecration.

Through profanity, our language became inexpressive, rotting from the head down. But we only later realized that there were certain things that “Millennial Snot” was incapable of expressing. The way of speaking that we all adopted, in order to be ironically immune to criticism and introspection, cut us off from poetry, solemnity, and sincerity.

And “sincerity” will forever be the largest failure of the Millennial generation. We all set out to find sincerity in our lives and escape the trap of Gen-X irony, but we all failed. What we did not understand was that one cannot be sincere without being vulnerable, and to be vulnerable, you have to be able to speak in a way that reveals Truth as it is and not behind a veil of profanity-laden snark and performative self-depreciation. “Millennial Snot” was Tolkien’s Black Tongue of the 21st century, and, like Sauron’s language did to the Orcs, the snot bound us to a type of spiritual slavery.

I make this digression about profanity because it is in our language where we encounter the problem of illiteracy at the most fundamental level and, therefore, its solution. We modern people find ourselves in a vicious cycle. Our illiteracy is driven by a spiritual absence, but our pursuit of new meaning is stymied by profanities backed into our very language itself, making it hard to obtain something higher. In order to reach out of the pit and towards salvation, we need a new map of meaning and spiritual symbols that can help us discern good from evil, a new way of incorporating Logos into our lives, our relationships, and our patterns of existence.

The Word must become part of our lives, part of our daily fabric, part of our flesh. And those words that we allow into our beings this way must be good. The symbol must be sacred.

That’s one virtue of BookTok. For all its degeneracy, brain rot, and narcissistic illiteracy, it understood one truth above all others. Books cannot be read to be appreciated as mere data. Books must be integrated into a person’s life, and your relationship with their form must be public. Certainly, BookTok was never able to utilize that anthropological understanding to benefit humanity, as its understanding was grounded in the world of solipsistic women and effeminate men, and its foundation was built on the internet. But any more serious endeavor looking for real spirituality will have to make use of the same modes.

Reading history, we hear of concepts like “people of the book” or “a man of letters.” While out of use almost entirely in modernity, these phrases represent a forgotten wisdom about literacy, namely that language must become internal to one’s identity to be wielded in a noble way. Moreover, a person’s intellectual identity must be developed through sacred archetypes that separate ugliness from beauty and the sacred from the profane.

There must be patterns of life and behaviors people perform, almost ceremonially, that rediscover meaning, cultivate their appreciation, and preserve it from the destructive force of entropy. And to this point of cultivation, I return to the paired archetypes that both Dante Alighieri and Frodo Baggins looked towards as guides across the lake of fire: Virgil and Beatrice, Gandalf and Galadriel, the Patristic guardian and the Marian Illuminator, the scholar and the poet.

The Archetype of the Scholar

Starting where it seems logical, it only stands to reason that a rediscovery of the scholastic begins with the archetype of the scholar.

Here, I use the term “scholar” loosely, since the modern understanding of scholarship has been reduced to winning petty academic status games in the most pretentious and superficial way imaginable. I could say we need a new understanding of “scholarship” in the sense that we need to reset our entirely broken university system, but that is not the same sense in which I think we need to rediscover the archetype of the “scholar” as it existed in pre-modernity.

In the ancient world, scholarship wasn’t about knowing things or having read a lot of books, much less having a brain capable of raw computational power. Being a scholar was a matter of wisdom, understanding less a map of the physical universe and more a map of the world’s value and the role its related symbols might play in constructing a better future.

Like Gandalf in Lord of the Rings or Virgil in The Divine Comedy, the scholar is a person who knows the realm of possibilities, points in the direction of goodness, and, more importantly, warns against the evil that might lie in wait for the hero along the path of error. That’s why the protagonists listen to these characters. It’s not because they know the facts (though that might also be an asset). It’s not because they possess great scientific skills or have access to technology that can get the job done. It’s because they possess wisdom.

For example, despite being a magic-user canonically, Gandalf rarely uses magic. He is not a conjurer, nor a magician, nor any wielder of technique. He is much less of a sorcerer than he is a prophet. His role is not to enchant, but to guide the heroes with intuition, through the words he speaks and doesn’t, towards the good and away from temptation, just like Virgil guiding Dante through the perils of Hell, just the opposite of what modern “scholars” do in modernity.

Ultimately, everyone needs guides in life that warn them of pitfalls. But in the modern world, we have generally characterized this role as entirely negative, especially if it deals in terms of prohibitions or “shall-nots”

What’s that? Are you letting someone else tell you what you should or shouldn't read or watch? Are you letting someone else tell you how to think? What kind of person would do that?

In the modern age, we might call such people critics, perhaps even censors. Neither term is flattering. As we have learned from the history of the 20th century and pre-modernity, censorious people are petty tyrants and busybodies who want to inflict punishment on others looking for truth outside of the system. Certainly, of all the elements of the pre-liberal state, the tradition of censorship is the last thing any of us would want restored.

And isn’t thought control the last thing a dissident would want, even if they call it “guidance,” even if they perceive it to be wise?

I understand this anti-censorious sentiment at a basic level. I feel it every time I have to deal with the petty thought regulation of the modern American “liberal” regime. No one wants to be that small man who guards the restricted books section at the library. Nor do many of us relish filling the shoes of the critics who run down works of art they could never create. People are right to scorn the likes of Nina Jankowicz singing Mary Poppins songs about misinformation. And I still take to heart Whit Stillman’s observation in Metropolitan, that literary criticism is often the refuge of pedants.

However, is the role of the censor and critic so easy to dismiss in the modern world?

It’s hard not to notice how culture has gone downhill since we stepped away from the critical and censorious culture of the past. Moreover, even as the restrictions imposed on the intellectual habits of people might be irritating, we modern people would do well to remember the undeniable evil against which all censorship was directed, an evil concisely contained in the meme:

“Let People Enjoy Things!”

This phrase, “Let People Enjoy Things!” is actually a line taken from a famous Owen Cyclops comic that has been living rent-free in my head for almost half a decade now. The phrase encapsulates a fundamental aspect of the Millennial attitude towards all cultural texts. It is the attitude of Reddit. It is the pose of libertarian license that can be found on both the right and the left. It is the pseudo-Nihilistic message that was fed to our generation across countless Adult Swim Cartoon shows and movies.

As this perspective goes, there is no meaning in life; existence is just a silly accident; and, as such, the best thing you can do is just enjoy yourself, chill out, and maximize the amount of pleasure that you can get out of life through the silly things that you enjoy. The only thing that can be considered bad is prohibiting things. The most asshole move you can make is to “Yuck somebody else’s yum.”

This pleasure-focused (non) worldview can be made to sound profound. It is also a convenient way to dismiss challenging ideas from previous ages without even understanding them. However, the logical conclusion of “Just Let People Enjoy Things” is simply rank hedonism with an existential twist. Young people might call such an epicurean perspective sincere, as hedonism is natural to people early on in their development. But as Dante discovered early in his journey through the inferno, hedonism isn’t just bad for you, hedonism is also just plain bullshit.

“OMG, just let people enjoy things!”

But we CAN’T just “let people enjoy things”. That’s not how the human mind works. Plain Hedonism is degenerative at its core. And the more we just let people enjoy things, the less meaningful and enjoyable they ultimately become. Witness the birth of “slop world.”

This is the critical truth that Millennials missed, but wise men of previous ages knew. Humans are restless in spirit. They can’t just live for the pleasure of the experience because humans ultimately aren’t looking for pleasure. They are looking for meaning. They are looking for God.

People (men in particular) need to know that the culture they consume is good, not just pleasant. Furthermore, thinkers need to engage with these challenging but good artifcats, even if they don’t enjoy, even if they struggle to understand them; and, to the extent that people slide back into base hedonism, they need to be shaken out of it, warned of the past, and guided out of the dark forest, even if the road to salvation leads through Hell itself.

Does that mean we should embrace censorship and the return to a syllabus of errors?

Perhaps, but at the very least, it amounts to some form of patriarchal guidance, a recognition that authority exists and that what we are doing when we engage with media isn’t simply an endeavor in literary onanism. At some point, civilization must draw a line between good and evil, and police the distinction between the sacred and the profane. And slowly, more and more people are coming to understand the necessity of a person who plays just such a role.

And perhaps this new perspective offers some insight into that great mystery: why, on the modern internet, while film and film culture appear to be dying or dead, has film criticism never been stronger?

Look at the top channels on YouTube, at least among those with a quasi-political bent, and you'll find that they are largely focused on criticizing pop culture, nerd culture, and Hollywood movies. From Mauler to the Critical Drinker on down, it seems like there isn’t anything more popular than humorously criticizing the latest movies from Disney and Netflix, even to an audience who has largely not seen them.

People are right to notice the irony of YouTube film criticism. Viewers don’t care about Hollywood, but they nevertheless spend hours criticizing its products. And isn’t it odd that many of the critics themselves can’t actually produce a passably entertaining popcorn flick, despite having ample resources to do so?

However, I am not so sure that this desire for relevant modern media criticism is misguided, even in an era with little relevant modern media. After all, modern people stand on top of a glut of cultural production with a corresponding dearth of meaning. Past generations have bequeathed us an endless amount of text, film, and digital entertainment products. But young people are left with no purpose, and no standard to discern which pieces of that entertainment might uplift them from their cynicism.

It is not surprising that the generations who experienced the full extent of cultural permissiveness and access to information now seek a tool to provide discernment rather than variety. Increasingly, when young people look to tradition or lost heritage, they are seeking guidance and a standard that can draw a line in the sand and say “no further,” defining the distinction between the sacred and the profane. Hence, there is a need for true scholarship and scholars who can embody the role of spiritual guide, which neither modern academics nor modern internet luminaries can fill.

Everyone in our generation is looking for a spiritual commitment that will take our feelings about the horribleness of the modern moment and translate them into a higher calling that can be meaningful and generative. In fact, that’s why many on both the left and right turned to politics.

But politics is not the answer. Only God is the answer. And it’s not easy to find Him, not without a guide, not without mentorship and correction, and with someone who can point in new directions, no matter how often the mark is missed.

The Archetype of the Poet

As I began this series with the death of book culture and followed it up discussing the death of film, it feels natural here to conclude with a discussion of another dead media form, in fact, the oldest form of dead media: poetry.

In truth, poetry died in the 20th century, and not very late in the 20th century either. By the time I was born, people had largely stopped reading it and reciting it. The last notable poet who was a household name, Robert Frost, had died decades earlier. Even the people who taught poetry at the local college didn’t so much appreciate poems as they appreciated being seen as the kind of people who enjoyed poems.

Yet, I was assured by all of the people around me that poetry was important and that to be a poet was something sublime. But this assessment only seemed to demand a follow-up question about why it was so important to create a type of media that, very plainly, no one in the modern world read or appreciated.

Why was poetry important?

Was it just about rhyming and meter?

Was it just about the beauty of the word?

The common explanations about the importance of poetry that I received from parents and teachers never made much sense. Perhaps it was all magical thinking. The older generations were responding to a certain sense of enchantment that the old world had felt regarding verse. But wherever this enchantment was in the modern world, it certainly wasn’t in poetry, and the extent to which younger people found their connection to a numinous spirit, we found it in our contact with pop culture and popular music.

Now, fast-forward 20 years, and these forms of popular entertainment themselves feel tired and archaic, either embodying a type of futile historical perspective characteristic of ‘period pieces’ or, even worse, capitalizing on a feeling that has long since passed, reduced to empty nostalgia. Suddenly, nothing has meaning, and everything is an empty signifier infinitely replicated for mass consumption.

Welcome to “Slop World”. Welcome to “Stuck Culture”. Welcome to the “Semantic Crisis”.

The era was brought about by a culture that had lost its sense of spiritual direction, it was accelerated by internet culture, and then reached its apotheosis in the era of A.I. with the introduction of LLM technology. Now, not only do we lack contact with historic meaning, but the very semantic tools we have for highlighting the spiritual importance of a piece of media have become confused.

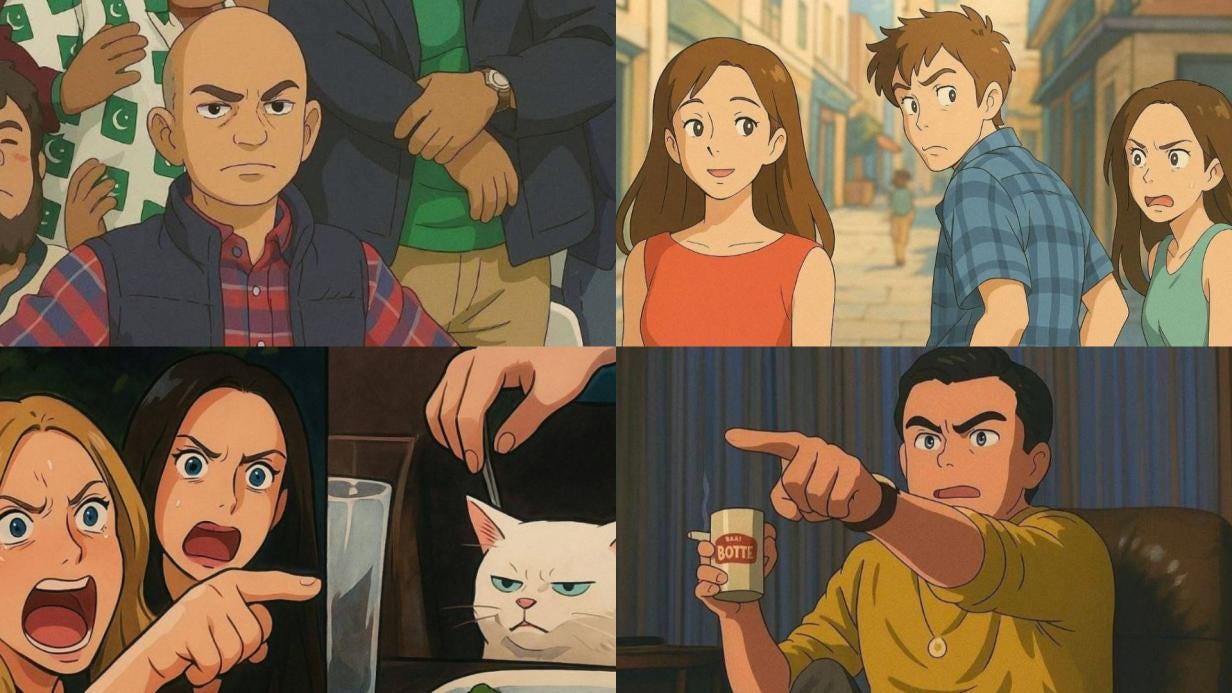

Case in point, recently I can tell a number of people were quite troubled by the advent of certain high-quality A.I. image filters, specifically the filter that converts any image into it a cartoon in the syle of Studio Ghibli, like Kiki’s Delivery Service or My Neighbor, Totoro.

Perhaps the Ghiblification of images is just innocent fun. After all, who doesn’t want a Ghiblified photo of their kids? But people immediately noticed the danger. Given the extreme cultural importance that modern (mostly Millennial) people place on the work of Studio Ghibli and Hayao Miyazaki, the association of this style would inevitably be cheapened, especially as the use of the filter bled down from personal photographs to the less wholesome side of the internet.

When every image appears within the semantic form of innocence, then nothing reads as genuinely innocent. When every spicy meme is cloaked in aesthetic meaning, then nothing can be identified as meaningful based on its appearance. It seemed, at once, that perhaps all profundity and originality might be robbed from human art by endless LLM duplicates, the semantics of human purpose buried under a sea of simulacra.

And now many people are worried that AI may be the end of human meaning in art. But it’s only the end of meaning for people with an impoverished understanding of meaning.

Case in point, I remember early on in the LLM explosion of 2022, the “A.I.-maximalist” crowd posed a rather dishonest riddle to skeptics:

“Can you give some objective intelligence problem, with formally defined rules, that human intelligence can solve but that the L.L.M. cannot?”

The question doesn’t have any good answers. But it’s also a trick question. By definition, the formal logical rules of the problem make its solution replicable by deep learning algorithms. That’s what they do.

Still, my own favorite answer to the trick question, “What can’t A.I. do?”, is simply “poetry.”

Ask trick questions, get trick answers.

My answer is a trick because writing poetry is one of the easiest challenges for Artificial Intelligence. Even before the age of deep learning, computers could generate verse with rhyme and meter. And, despite what people might say otherwise, those old-school poetry generators did create some banger poetic expressions.

But still, computers can’t write poetry, even if computers can perfectly imitate poetry, technically. This is because technical imitation is not what poetry is.

Poetry is the embodiment of a personal experience as it attempts to connect with another personal experience through the medium of words. Poetry is a communion that allows us to share with others their struggles and joys, as well as their experiences of life and death. To be poetic, the verse as written must symbolize a connection with a person, with God, or with a collective. Perhaps all three. John Donne wasn’t lying about the tolling of the bell.

The act of writing poetry is that of establishing a specifically personal connection that expresses the numinous. Poetry is the communication of a message between two souls, even if those souls are living or dead, collective, or divine in nature. The fact that such a message can be faked does not diminish the importance of the authentic communication, just as a counterfeit currency cannot diminish the value of the authentic issue. The imitation of the genuine production only destroys value to the extent that the parties themselves are deceived. And the counterfeits have no ability to produce such value independent of the original.

To be a poem, a true poem, the verse in question must link the reader into the great chain of being, leading from the beginning of time and the first word spoken, through the present, and on into the end of history, and the last verse recited. We encounter this lineage in our own time, through the words we use and their symbolic meaning that our ancestors bequeathed to us. Then, based on our experience and struggles, we try to take the next step, grasping for the movement of divinity in our own time, our Zeitgeist, falling short and missing the mark, or getting closer, stumbling forward to follow humanity’s ultimate destiny within history.

This is the ultimate role of the poet or troubador, the person who embodies the human spirit and its juxtaposition against history and nature. This is the human inclination to song and beauty, the way that we discover new sacred things that need to be rescued from the profanity of modern times, the discipline that we lost in liquid modernity.

Moreover, the practice of poetry is a collective practice. It belongs to everyone within a society. Certainly, very few people can write passable verse, and even fewer can hold a mirror to the face of a time and place to glimpse Truth, as all poetry should. But that’s hardly the only point in practicing poetry.

Really, the more important aspect of having a poetic culture is simply living in poetry and being the type of person who can receive poetic wisdom. To that end, every person within the greater collective has a role to play. To live romantically and build that sense of beauty into the language itself, to create a language that underlines the communal understanding of the sacred, just the opposite of “Millennial snot”.

Many people think such a rediscovery of enchantment is impossible, but I think you can see such a pattern of enchantment in fragments, even in the highly degraded modern world. Young people already look to pop culture for meaning. They seek purpose in their movies and music. From rock to hip hop, young people know that lyrics aren’t just lyrics, and they all choose “anthems” that characterize their own poetic interpretation of the universe. And isn’t the same union of meaning and symbolism happening within meme culture online, even if the results are degenerate and crass?

My hope for restoration is simply this observation: that humanity’s path towards essential meaning is guided by the form of language. And, while it might be a cliche, it is true that words structure thought. If the use of profanity can profane our thoughts, severing us from spiritual communion with our ancestors, then certainly rediscovering and using sacred language can restore our understanding of meaning and Logos. Those who attempt to reforge these human bonds through the language they use are occupying the role of poets, even if they write no verse and recite no lyrics.

I know that some people might find this vision of a linguistic and literary renaissance somewhat neat in the face of the modern crisis. And indeed, the archetypes of restoration that I have selected, both in the scholar and the poet, are based largely on my own experiences. What matters is less the form of the rebirth and more its essence, to look at the great volume of cultural work that we encounter in our own time and see it as an opportunity to commune with a spiritual Truth and to make it part of ourselves at a personal level.

Our age is characterized by fear. We are afraid because we feel, at some level, that we are unequal to the tasks this age requires of us. The old comfortable world of late modernity is coming to an end. Something else will fill its place. Now, the younger generations sit at the crux of these developments, trying to prepare for a series of decisions that their education never equipped them to handle. We must sort through the remnants of the old world, locate what we feel is truly good, and use it in combination with our experience to build something better for the future.

The task that greets people living inside the post-modern condition is enough to strike anyone with a sense of vertigo. But in all of the fear, I hope that more people recognize the great opportunity that lies before us.

In this moment, we have the chance to read the words that vivified the old world, discover within them their implicit beauty, and find ways of expressing that beauty which makes the numinous legible and the profane indiscernible. We might have many names for this process, but in all our efforts here, we are discovering a new language to replace the old one that was lost. And whatever path we take, there will be a new link forged in the chain that connects the Alpha and the Omega.

Does that mean leaving some things behind?

Almost certainly.

But what really matters will last. Because even as we separate and reform inside the chaos of this new age, the Word made flesh will stand unchanged and unmoved, and in its light we shall have meaning, even if we lack the language to express it, in so many words.

Your take on censorship and “Millennial Snot” reminded me how, even as a right-wing type, I used to consider any talk of restricting language as archaic or tyrannical. But now I see the spiritual impoverishment around us, especially with how profanity and irony have choked out our capacity for reverence. I love how you link it to Tolkien’s Elvish vs. the Black Speech—once we let the “Black Speech” style dominate our daily talk, we lose the vocabulary of transcendence. Living for cheap laughs ends up strangling the ability to express awe or depth.

This is brilliant! I feel spiritually uplifted after reading it.