Civilizational decline is anticlimactic. For all our contemporary fascination with collapse, degeneration’s lived experience is humiliatingly ordinary. It’s just a series of broken systems, ruined people, and things falling apart.

Anyone who can remember the “before-times” knows what has been lost. The feeling is not just nostalgia. We used to live in a more interesting world. Society once had more purpose, the world held more meaning, and culture was more relevant. The notion only stings harder when I consider that much of this decline is the consequence of my generation’s deliberate cultural vandalism.

It's probably “not a good look” to blame my own Millennial cohort for the sorry state of our modern culture, especially since I once participated in most of its bad habits. But then again, we should speak plainly and take stock of the many things that were destroyed in the last few decades.

At one point I thought it might be interesting to write a comprehensive list of things ruined by college-educated Millennial progressives. From movies to rock music to theater to foodie culture, this list wouldn’t be short. But somewhere at the top, I would probably list books and their transformation into what I have come to call “book slop.”

By “book slop,” I don't refer to the medium of knowledge and storytelling for most of human history, but rather the Millennial cult of social status organized around words printed on paper, bound in an illustrated cover, and expounded on endlessly. “book slop” does not impart useful knowledge or memorable human stories. “book slop” does not exist for spiritual edification. “book slop” does not contain challenging ideas. Instead, “book slop” exists to be consumed without consequence, to affirm one’s life without greater examination, and, most importantly, to show the world the kind of person you are.

“Book slop” is bought from novelty boutique bookstores, carried around in colorful tote bags with popular political slogans, and displayed prominently in coffee shops. “Book slop” is organized into color-coded bookcases ready to be photographed and discussed endlessly on social media to establish one’s superiority over the rest of the unwashed masses who didn't read it.

And in 2024 “book slop” has subsumed every inch of what was once the world of Arts and Letters in a planet-wide literary longhouse. Now, every collection of short stories is edited by the same urban AWFL type with a career modeled on Joyce Carol Oates, every bookstore is less about books than in selling accessories to the "book slop” lifestyle, and every conversation concerning the written word inevitably returns to substance-less popular novels or thinly veiled political diatribes masquerading as serious non-fiction.

Presently, “book slop” culture may have reached its execrable apex on America’s newest, most mindless, social media platform with the phenomenon of “BookTok”, or “book fans” as they organize themselves on the social media platform TikTok. And because it's the current year, “BookTok” just couldn’t be a proper online sensation unless it represented the absolute worst aspects of everything that came before it. Here, you will find the egotism of the Boomers, the soulless snark of the Millennials, and the mind-numbing brain-rot of the Zoomers come together like the powers of the Planeteers, summoning Captain BookTok to spread the bilge of post-literate literary culture far and wide.

On BookTok, novels are just accessories of “profilicity”; intellectual standards are in a constant race to the lowest common denominator. Meanwhile, the attitudes of pedantry have discarded the pretense of even being at all aspirational, replacing the more challenging fair of previous generations of book snobs with the trashiest fan-fic style fantasy and romance imaginable. And even reading that limited fare might be optional in the world of BookTok, where the very practice of reading is secondary to the task of reveling in the eternal glory of undifferentiated books. One of the most powerful mediums of human communication and Enlightenment reduced to another avenue of my own generation’s narcissism.

I should admit that this transformation was not simply the product of one generation. Yet we are very far from the time when the likes of Dickens and Tolstoy were recreational reading for the middle classes, even if it wasn’t actually that many decades ago. In the early 20th century, the world of the written word was serious. It was a ponderous place where books had a weight to them. Yet across the last 100 years, the phenomenon of mass literacy degraded from Leo Tolstoy to Boris Pasternak, from Norman Mailer to David Foster Wallace, from Michael Crichton to Stieg Larsson. The process was continuous, barely perceptible until we arrive at 2024 when a substantial portion of college-educated “readers” consider Stephanie Myer, a serious author and are unable to appreciate literature outside the purview of “Young Adult Fiction” (YA).

Many on the right blame the decline in the quality of literary culture on changes in gendered reading habits. Women read and write more, while men are increasingly absent from what was formerly considered a masculine art. Certainly, the phenomenon of cultural feminization is readily observable. There was a transition, very visible throughout my own life, where the older, more masculine literary culture was put away and replaced with another altogether more female-oriented perspective.

Up until the late 20th century, reading books (and writing books) was seen as an eminently masculine endeavor. It involved creating a bold human space, exerting will upon the language and the page, and boldly advancing new ideas that could change the world, as seen in the heroic writer archetype from Homer to Ernest Hemingway.

Then, somewhere along the way, this understanding of literature faded away, and books were re-conceptualized as fundamentally an exercise of empathy and emotion, a feminine space dominated by new masters like Margaret Atwood and Barbara Kingsolver, who were able to center the sacred victim and bring their emotions to life. Subsequently, the culture of the modern novel definitively matches this new understanding of the purpose of literature.

However, the problems with modern books go deeper than gender. We are not witnessing a mere change of forms. We are not seeing a declining masculine energy eclipsed by a rising feminine one. There is no emerging female literary genius in the early 21st century. Women’s reading habits are worse than ever, and the writing on offer from female novelists is more shallow than it has been in the last two centuries. Instead, the world of literature has contracted across the board. The pond of human imagination has evaporated, shrinking down to a fraction of its former breadth, with the female specimen surviving the contraction only because it required less space to begin with.

In this case, the decline of literacy across generations follows the same pattern as all other cultural degeneration. First, the spiritual essence of the practice is undermined, and the teleological reason for its existence is minimized in favor of the circumstantial properties of its form. Then, as time goes on, the form itself crumbles, with every element of the original specimen replaced by simulacrum until it remains a hollowed husk, unable to provide its original meaning; its associated emotions remaining only as half-forgotten cultural nostalgia.

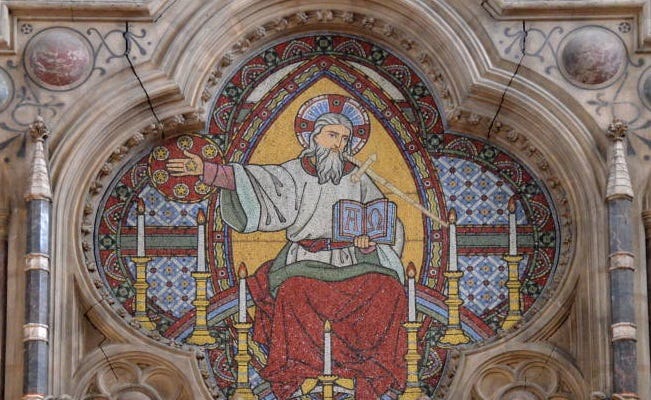

The spiritual teleology of the book is Truth, Spiritual Truth; the kind of truth that humbles egos and brings empires low; the kind of words that, if written or spoken at the right time, make the pillars of civilization shake and the mighty fall from their towers. The book was important because it could contain words that were greater than the people who read it or even the civilization that produced it. The Word was with God, and the Word was God, and with the discovery of the True Word, the world we knew might end, or a new one might begin.

But modern people aren't supposed to believe in the spiritual power of the Word. In modernity, media is simply a tool. Books are simply information. And mere information can’t be greater than the use a person has for it at any given moment. Nevertheless, something deep within our post-Christian souls still wants books to contain magic beyond their utilitarian existence, and so our culture seeks to repeat the form of the holy book without actual belief in any transcendental holiness, and our understanding of literature as spiritually meaningful persists as a dead cultural form.

I remember encountering this dead cultural form as a precocious boy who preferred to spend his recess time at the school library. Of course, I liked books, some books at least, the ones about dinosaurs or furry forest animals fighting in medieval battles. But as genuine as my enjoyment of these stories was, and as much as my fascination with books allowed me to “tap” into a larger world, a substantial part of my identity as a young reader was most certainly affected. After all, this wasn't the 19th century, and books weren't the only way to experience other times and places. We had television, movies, and even video games, and any honest kid, despite how much they loved books, would have to admit that those other mediums were much more exciting and amenable to our short attention spans.

Truth be told, much of my early childhood fascination with books was inculcated in me by adults. As Millennials, we were endlessly fed a strange propaganda of the written word, we were told that books were important and wonderful, even though it was never clear what specific information they contained that couldn’t be communicated in a movie or an audio recording. Furthermore, there was a certain prestige in being that young child who decided to invest themselves in reading large books, being the infamous “kid who reads.”

Oh, to be the kid who reads! It was truly the apex mode of early-life Millennial narcissism. And it felt so real, so grounded, so true. We were the children who wanted to spend our time in a more contemplative way. We were reaching into a larger world beyond the boundaries of what we might find on the playground. Better yet, our decision to spend time reading was an indication that we had promise, open-mindedness, and maybe even a role to play in greatness. We were so much better than all those kids who used their time to play stickball or join sports teams. They were probably just bullies anyway!

It wasn’t until much later in life that I began to realize just how artificial this identity was. Being the "kid who reads" was not remotely uncommon. Furthermore, these romantic notions about reading I had as a child were largely received from the outside. We got these notions first from Hollywood, which gave us heroic archetypes of the bookish child, like Lisa Simpson and Bastian from The Neverending Story. And these images were reinforced by a certain cohort of progressive-minded Boomers convinced that these books would inevitably lead us in the direction of their preferred worldview. What was initially portrayed as an unbounded journey of exploration into all past human thought was actually more of a curated tour with established on-ramps, exits, and no-go-zones.

Certainly, I do not wish to cast aspersions on the generations who came before me. The adults in charge of our education, progressive or otherwise, were sincerely giving us the best that they knew. They had been raised with a certain belief in the magic of reading that had been carried over from the old Christian world. And even though they didn’t themselves believe that God might be reaching out to guide our thoughts through the medium of the words we were reading, they nevertheless believed in some higher good that was, in some vague way, locked in the pages of the books written in the distant past. Our teachers wanted to lead us to a greater good, even if that understanding was marred by their political ideology.

However, despite their sincerity, the heritage that the Boomers bequeathed to their children was fundamentally incomplete. It was a headless cult of discovery where the moral center was absent and replaced by a non-specific goodness that the readers would have to discover for themselves. Reading was an altar to an unknown god. And, in typical human fashion, we Millennials took the next logical step and replaced that unknown god with our own egos. It was a divine narcissism that began originally with our dedication to the sacred book.

Perhaps then, it is no surprise that this attitude followed my generation to college, where the key to winning any argument was being perceived as the one who had read the right things. Even before social media started properly, everyone wanted to be the smart guy who laid the truth down hard, everyone wanted to be Matt Damon from that famous scene in Good Will Hunting. As such, the point of any discussion concerning books was less to explore their ideas than to demonstrate that you were the person who had consumed more books, the thinker who was “better read.”

Did it matter what the books actually said? Not really.

The point was the list that you could prattle off to demonstrate that you were up to snuff and that your interlocutor still needed to do work in order to “get on your level”. The goal was to be the person who won the “have you read it” game, the endless checklists of identical books you could claim needed to be read to be “educated” and in the know. Almost all Millennial progressives played this game and enjoyed it even though we knew it was petty. In fact, we would mock ourselves for doing so when we thought no one else was watching.

There was only a limited understanding that books might contain unique perspectives or meanings because books existed as mere instantiations of our class egotism, designed to reflect our cohort’s native liberal sensibilities in a maximally flattering way. Of course, books all had the same point of view underneath it all. How could they not?

If a book conveyed valuable information, it would inevitably complement the reigning modern worldview and the academic experts who were its arbiters. Otherwise, if a text opposed that consensus, it was probably defective, a product of an ignorant, unenlightened time, and needed a critical reinterpretation to be properly useful. This perspective formed the perfect Catch-22 in support of the intellectual status quo. Any number of books could be fed into one’s mind, but no new perspective could ever be gleaned.

That’s the strange thing about a worldview organized around narcissism; it never reaches for anything higher than itself because it can’t acknowledge anything higher than itself. Instead, narcissistic cultures tend towards conformity and a central set of opinions that optimally validate the group. As such, modern education isn’t about understanding and curiosity. Modern education is about having the right opinion about things. It’s about being able to use the right language, which allows one to be perceived as part of the right-thinking group. In fact, as a modern intellectual, one isn’t a thinker; one is a repeater, a co-conspirator in the giant project to maintain the illusion that modern intellectuals are intrepid individuals who have mastered the world, even if they never have to deal with any distasteful or challenging ideas.

It is just this attitude that has caused so much modern academic writing to become little more than extended bibliographies prefacing extended conclusions, the actual arguments disappearing in between the bookends like a thinly sliced cold-cut sandwiched between two giant baguettes. In the current year, writing is not designed to actually contain thought, much less commend an idea or analysis, but to be an optimal node in the neural network of the expert consensus. Modern academic publications are simply machines to transform a list of citations into an academic impact score, increasing one's clout in the group with the minimal amount of thought possible, the fundamental impoverishment of the intellectual endeavor.

Given the conditions of modernity, I suppose that it was always going to end up this way. Still, it never ceases to amaze me how quickly the process of decline accelerated during my own generation. Something was different about the Millennials. There was a quality that my generation picked up somewhere in our education that seemed to make them relate to culture differently, a quality best described as “Media Literacy.”

In 2024, I probably don’t need to explain “Media Literacy” to many readers. But its emergence as a ubiquitous trope online is still interesting to revisit. Suffice it to say, in the early decades of the 21st century, just as progressive orthodoxy solidified its grip on the mainstream, a great insecurity overtook leftists. The progressive narrative was dominant, mainstream Hollywood creators were producing content exclusively designed to bolster their worldview, the mainstream press was in lockstep with their cultural agenda. But there was a cost to this dominance. Progressive thinkers had been left incapable of discourse, out of ideas, and locked within a coalition that was too large and brittle for its own good, and tied to a future vision that was in the process of crumbling.

More to the point, modern progressives didn’t really know what to do with the cultural artifacts they had inherited from eras less dominated by left-wing ideology. Previously, older generations of progressives, who had looser grips on their worldview, would have engaged with the works as they were and built the challenges into the substance of their politics. However, the 21st-century leftist worldview is too fragile. The second the ideology admits to the existence of a legitimate alternative, it shatters to dust, collapsing under the weight of its own inability to sustain criticism.

Enter the internet phenomenon of “Media Literacy”, the ultimate solution to all problematic media. As it is used, “Media Literacy” conceptualizes non-aligned texts, especially older texts, as essentially didactic in nature. The point of experiencing any media content in a “literate” way is to discover the ideological message or the counter-ideological heresy, validating the former and denouncing the latter. As found in the famous words of the scholar, “Everything is racist, everything is sexist, and you have to point it all out!”. The experience of art, therefore, becomes a straightforward academic exercise. As such, not arriving at the progressive answer means not completing the assignment as given. It’s a personal failure.

What, you didn’t understand the secret queer theme in Hamlet? Yikes, my dude. That’s not a good look. Are you even literate in media? It sounds like you have some homework to do.

This last year of 2024, the most prominent example of “Media Literacy” discourse surrounded Isaac Young’s critique of Paul Verhoeven’s 1997 science fiction epic Starship Troopers, a pastiche of Robert Heinlein’s 1959 novel of the same name. While seemingly a rather innocuous thread about a movie released almost three decades ago, Young unwittingly kicked off a deeper conversation about the nature of satire inside entertainment media, specifically concerning the true meaning of the movie adaptation of Starship Troopers.

As it would seem objectively, Robert Heinlein intended the mid-20th century novel to be a rebuttal of America’s growing pacifist sentiment. And, at many points in Starship Troopers, various characters offer up extemporaneous monologues concerning the nature of war very much reflecting the author’s political opinions.

Certainly, Heinlein himself possessed rather opaque political attitudes, falling neither on the right nor the left side of the political spectrum. Nevertheless, Starship Troopers very much embodied the author’s frustration with the progressives of his time, and as American culture gradually shifted leftward over the years, the novel’s right-wing perspective became more noticeable to readers.

In response to this legacy, Paul Verhoeven created his 1997 film as a progressive answer to the original, reactionary science fiction classic, lampooning Heinlein’s vision of a militaristic interstellar empire inside a schlocky crowd-pleasing action movie that broke up the violent plot with humorous over-the-top parody scenes. The director’s political opinions could not be more on-the-nose, as everything about his depiction of the Terran Federation is a direct callback to early 20th-century military governments, supporting Verhoeven’s perception that Heinlein’s original book was “fascist” even though he had never read it.

Perhaps the director’s unfamiliarity with the source material is the reason that his film’s satire never lands. In fact, as Isaac Young outlines, Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers works better as a right-wing celebration of the very militaristic values that the film’s auteur intended to parody. After all, the necessary components are there from Heinlein’s source material. The Terran Federation is locked in what seems to be an existential battle with aliens, requiring extreme measures that a civilian-led government would be most likely incapable of making. And even if some of the leadership is a bit authoritarian, it’s hard to see what a better alternative might be.

Moreover, despite Verhoeven’s satirical approach, the basic logic of his plot compliments Heinlein’s original perspective. The protagonists are all heroic good-looking twenty-somethings whose dashing actions look righteous even when they are accomplished in Hugo-Boss-style uniforms. Meanwhile, the villains are grotesque insects with zero empathy or humanity.

Altogether, Young’s critique was a well-made subversive interpretation of the text, certainly better supported than half of the subversive literary criticism I read in college. But for a solid month, Isaac Young’s observations melted the brain of almost every online leftist as they circled the original thread like a swarm of angry hornets, all buzzing the same monotonous refrain of “MEDIA LITERACY!”

What followed was not a conversation, much less a debate over differing media interpretations. There were no arguments. There was no discourse or conversation with different parties comparing alternative interpretations and pointing out how certain facts fell outside the other’s narrative. Instead, Young’s detractors simply took to explaining again and again that Verhoeven’s film was a parody intended to satire right-wing ideas. To interpret Starship Troopers in any other way was to lack “Media Literacy,” and that somehow meant you were a bad person.

Really, the progressive response was laughable on its face.

Did these online leftists not see Young’s acknowledgment of the director’s intent at the beginning of his analysis? Did they not understand that his interpretation was desgined to be subversive? Did these college-educated progressives never hear about “Death of the author”? Had they not read countless essays reading intersectionality or queer themes into pre-modern texts? Did they never laugh when watching Mystery Science Theater 3000 or watch Reefer Madness when they were high? Did they really believe that a text’s original intent provided such a straight-jacket for a reader that any attempt to break from its strictures violated the code of media literacy? Come to think of it, did Verhoeven violate the code of “Media Literacy” when he attempted to subvert Heinlein’s original theme without even reading his novel?

None of these questions mattered because “Media Literacy” meant that one singular, brain-dead progressive interpretation was authoritative, and nothing more needed to be said on the matter. For these leftists, the assignment wasn’t to subvert a progressive text, it certainly wasn’t to think deeply about the ideas in question. The assignment was to shoe-horn the media into a preexisting media narrative. And that’s what the online Millennials did. That’s what they always do because that is how they were educated.

Often, when witnessing the latest explosion of ideological nonsense online, people are too quick to dismiss the phenomenon, overlooking its deeper origins. The same is true with the “Media Literacy” meme, which actually originated in the academy as an endpoint of serious thought in the late 20th century. Starting with prominent post-war thinkers like Marshall McLuhan, who described how ideology was embedded in mimetic ecosystems, the field of “Media Studies” was further developed by luminaries like Paolo Freire and John Burger into a pedagogical framework that was subsequently taught to the Millennial generation in their formative college years. What began, at first, as an alternative way to politically interpret culture gradually became the primary way of educating young thinkers in the humanities, with “Media Literacy” almost entirely replacing the remnants of the classical approach to liberal arts.

The naturally left-wing origins of its adherents aside, I imagine that a large reason why the “Media Literacy” perspectives dominated the academy was due to the way the approach framed itself as a kind of technique similar to those found in STEM fields. Inside the framework of “Media Literacy”, professors were not indoctrinating their students with ideology, but rather giving them a set of skills that could help them “see through” the reactionary media ecosystem that would otherwise have hijacked their minds. Supposedly, students with “Media Literacy: were a step ahead of their classmates, able to maturely consume content from different perspectives, see through the propaganda, and better process challenging and different points of view.

Perhaps predictably, like most academic fads, the perspective of “Media Literacy” accomplished the exact opposite of its supposed purpose. The perspective produced a generation of thinkers supremely incapable of questioning their own preconceptions, locked into their own ideological way of viewing the world, and simultaneously convinced that everyone else was brainwashed and in need of a good re-education in “Media Literacy.” Thus, the archetype of the narrow-minded Millennial book-slop consumer was born, and the age of post-literacy began in earnest.

I mention the academic origins of “Media Literacy” because I think it’s important to understand modern illiteracy as an intellectual response to the emergence of mass media. Unlike many “classical liberals” or conservatives, I think Marshall McLuhan was more or less on the money when he described humans as developing their ideas inside a media ecology. As I always like to mention, Humans are not fact-processing machines; we exist within a social and cultural context that forms our ideas. Moreover, pedagogy and education can not exist in some isolated objective vacuum but rather depend on a concept of rightness and wrongness that must be indoctrinated into the mind of a believer at a pre-rational level, thus making completely neutral education an impossibility.

In the wake of 20th-century mass media, the assumptions of the late Enlightenment were failing. As such, I find it hard to blame the John Bergers and Paulo Freires of the world for trying to create an ideological response to these circumstances. The problems with their approach to media only started to develop due to their worldview’s conflicts with reality and their inability to honestly admit that they were in the business of indoctrination. Perhaps if these thinkers had internalized the understanding that humans don’t discard ideology but just trade one ideology for another, they would have had enough self-awareness to understand the flaws in their pedagogy.

It’s hard to say.

Either way, these thinkers’ successors in our modern academic class have committed themselves to a fundamentally false understanding of the world that has never had to answer for its own inaccuracies. Moreover, every time this ideology runs up against the facts on the ground, it inevitably reconciles its contradictions by re-framing what is morally important. And this process of “retconning” the errors of leftism out of history is almost always accomplished by contracting the scope of human aspirations and memory.

If the economic policies the left promotes make you poorer than your parents, just ask yourself why you wanted to be like them in the first place. Shouldn’t you be more focused on your relationships and the people around you?

If the social policies the left enacts destroy family bonds, ask yourself if your family was really an element of patriarchy. Shouldn’t you have higher spiritual callings than the people and society who raised you?

If the worldview the left advocates blasphemes God, scoffs at spiritual edification, and destroys meaning, just ask yourself if it's not better to be a hedonistic bugman who only cares about himself. Isn’t that what freedom actually means?

At each iteration of this process, the scope of human aspirations is narrowed in order to allow the ideology to justify its total control over the media ecosystem. It's a pretty neat trick, politically, as long as you don’t mind the inevitable degeneration.

But spiritual degeneration is what our society signed up for, and spiritual degeneration is what we got. The American mind eventually began to close into the confines of an ideological straight jacket incapable of processing anything more nuanced than a Saturday morning cartoon. Everything existing outside its preferred frame was whitewashed away as illegible, discarding outright the deep human messages that people really needed to hear.

This is the ultimate source of “the meaning crisis”, at least as it pertains to books and media. The stories of a Tolstoy, a Dickens, or a Dostoevsky can’t be perceived by modern people (much less appreciated by them) not because they are too old but because they are too large. They can’t fit into a modern mind. The ever-shrinking maw of the liberal imagination cannot open its jaws wide enough to take them in. And so these types of communication must be ignored, discarded like the mystifying runes of an ancient civilization. Even if these texts could be discerned, they wouldn’t mean anything in the context of the society we have been trained to occupy. Thus, as Spengler foresaw, our civilization enters its Winter Stage as its previous spiritual cornerstones become illegible to its children, the deep meaning that they contained falling by the wayside.

I genuinely had no understanding of the tsunami that was about to crash upon my account when I wrote that thread. The most peculiar thing I remember about that experience was that they take every admission of ignorance--even if it's only perceived--as a means to attack. I sent a tweet saying something along the lines of, "the only argument they are throwing at me is that I don't understand the difference between a parody and a satire"

I researched that for the thread so I was read up on my arguments. They were just throwing that accusation at me, but that didn't stop the masses leaping to the conclusion that I must've been an idiot. I got a million replies saying, "He doesn't understand the difference between a parody and a satire, lmao"

As if there had been a million English professors lurking on Twitter for that exact moment.

It vexes me as a teacher when I hear people say things like, “boys can’t sit still for long and read.” Who do you think used to write everything!?