(this article is part 2 of a series called “The Blessings of Babel”, the first part can be found here)

Often, dissident thinkers take a wrong-headed perspective towards societal decline. Ironically, critics of modernity adopt the very modern perspectives they ordinarily object to, conceptualizing an issue in terms of systems and systematic critique while ignoring the fundamental human quality that lies at the heart of the problem.

In a prognostic sense, these systematic perspectives are helpful, especially for describing an overarching decline and “seeing through illusions” of defunct political formulas. But they miss the forest for the trees and the spirit of the issue at hand. The technical birds-eye view can’t notice the living motivation behind the system itself, and so the critique is deconstructive instead of generative, describing the many ways that a system might die at the macro level but never the small ways that life can reestablish itself, the green shoots that might be growing at our feet and which might be helped by our attention.

Take, for instance, our original question of cultural literacy and the decline of the written word in the modern world. Looking at the problem macro-cosmically, the degeneration is impossible not to notice and (also) impossible to fix. The edifice that was the old world of arts and letters has been toppled, and it’s hard to understand how anything like it could be reconstructed. However, looking aside from the insolvable problem of fixing culture writ large, I still think there is hope for a rebirth of literacy at a smaller scale if we re-examine the issue of books in the context of human experience.

As McLuhan noticed, the way in which we consume media is essential. This is because the process of encountering a piece of knowledge has an informal quality that cannot be reduced to the base data that it contains. Just as the medium is part of the message, so too is the time and place where we experience it. There is no Protestant Reformation without the Gutenberg printing press and the Renaissance town square. There is no Socrates without the Athenian forum. And modern people’s media experience cannot be separated from the ways that they encounter that media. Likewise, to rediscover a more healthy literary culture, we have to begin where most people first encounter literature: the bookstore.

Certainly, in the age of the internet, even the concept of bookstores feels quaint. In a world with Amazon, most people don’t purchase books in physical locations, if they even purchase physical books. And the vast majority of modern reading occurs on the internet. In a way, the ubiquity of hypertext is unavoidable. Yet, when it comes to texts that are imbued with those sacred qualities that really last in our collective imagination, humanity always returns to the form of the book, which is probably why book aesthetics are built everywhere into the online experience.

When it comes to reading, humanity will never escape the physical book. And for those of us in the Millennial generation, physical books are inseparable from the brick-and-mortar bookstores where we first encountered them.

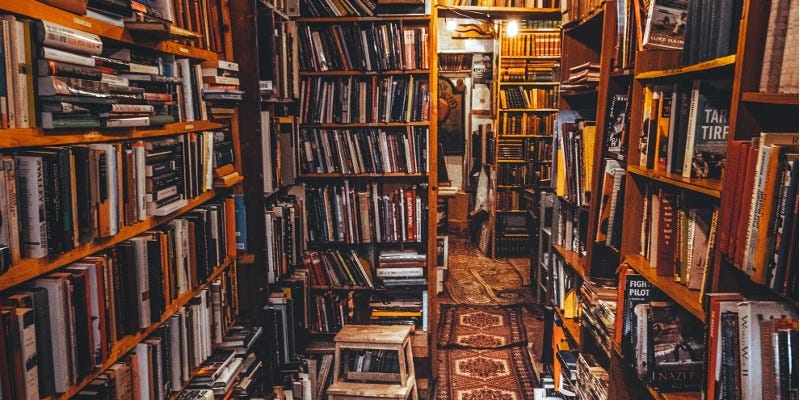

I will confess to having romanticized feelings towards bookstores, even though this is a quintessential “Kid Who Reads” type attitude. Still, there was something special about these places, at least as they used to exist. Bookstores, used bookstores in particular, contained a unique experience for any visitor who would enter. There, somewhere in between the hardwood floors, the creaking bookcases, and the smell of paper and book bindings settling into themselves, was a feeling of infinite possibility, a sense that there was meaning to be found within its walls and that through your searching within the pages that surrounded you, one was going to be acted upon by a more powerful spiritual force that might bestow on you eternal truth, if but you could make the right selection.

I imagine a similar sentiment was felt by previous generations surrounding libraries, a sentiment that made Western civilization adorn these buildings with heraldic statues. Still, for myself, child of the 20th century that I was, this feeling of transcendental logos always seemed to be located at the places where books were sold, for keeping.

Perhaps some of my romanticism is owed, in part, to my father, who founded his own bookstore as a retirement project in his later years. The shop only ran under his ownership for about a decade, but it provided me with a very memorable experience working as an assistant book-monger in the months between college and graduate school.

For my father, what made managing a bookstore interesting was the project of finding books that had been unjustly discarded and then putting them into the hands of people who could appreciate them. The general business worked in two stages: first, acquiring old books at cost, and second, shelving them inside the store and selling them to customers. My father always preferred the process of locating exceptional inventory among the detritus of book consignment sales, estate liquidations, and library surplus. Whereas I always preferred working the register, talking with the customers, and helping them find exactly the book that they were looking for.

The interesting thing about bookstores was that customers never walked in knowing exactly what they wanted. Instead, the decision concerning “what to buy?” was sought from the establishment itself. Not that the customers wanted to be told what to read directly, but there was an implicit understanding that the bookstore had a sort of guidance built into its form. The prospective buyer was taking a journey, browsing across an ocean of text with whatever time they had to spend. And, under these circumstances, the bookstore would direct them through its arrangement of books, its architecture, and the general ambiance of the store itself.

I speculate that it was just this feeling of spontaneous-yet-guided exploration that fascinated my father about bookstores. Even before he built his own, my father would make a point of visiting these establishments while our family was traveling, always making a point of locating the most unique and interesting books that the store had on offer and making at least one purchase out of courtesy to the owner.

The charm of used bookstores was their organic quality; no two were alike, and each seemed to represent a certain WAY of thinking. Some were organized boutique shops; others were piles of dusty tomes; some were large archival libraries, and others still were just holes in the wall where it seemed that the owner was trying to rid himself of the lesser half of his private book collection.

Touring through these establishments as an older child, I remember, at one point, asking my father a question common to many young boys:

“Dad, what’s the best bookstore?”

“That’s a matter of opinion.”

“But what’s the biggest bookstore?”

“That would be Powell’s.”

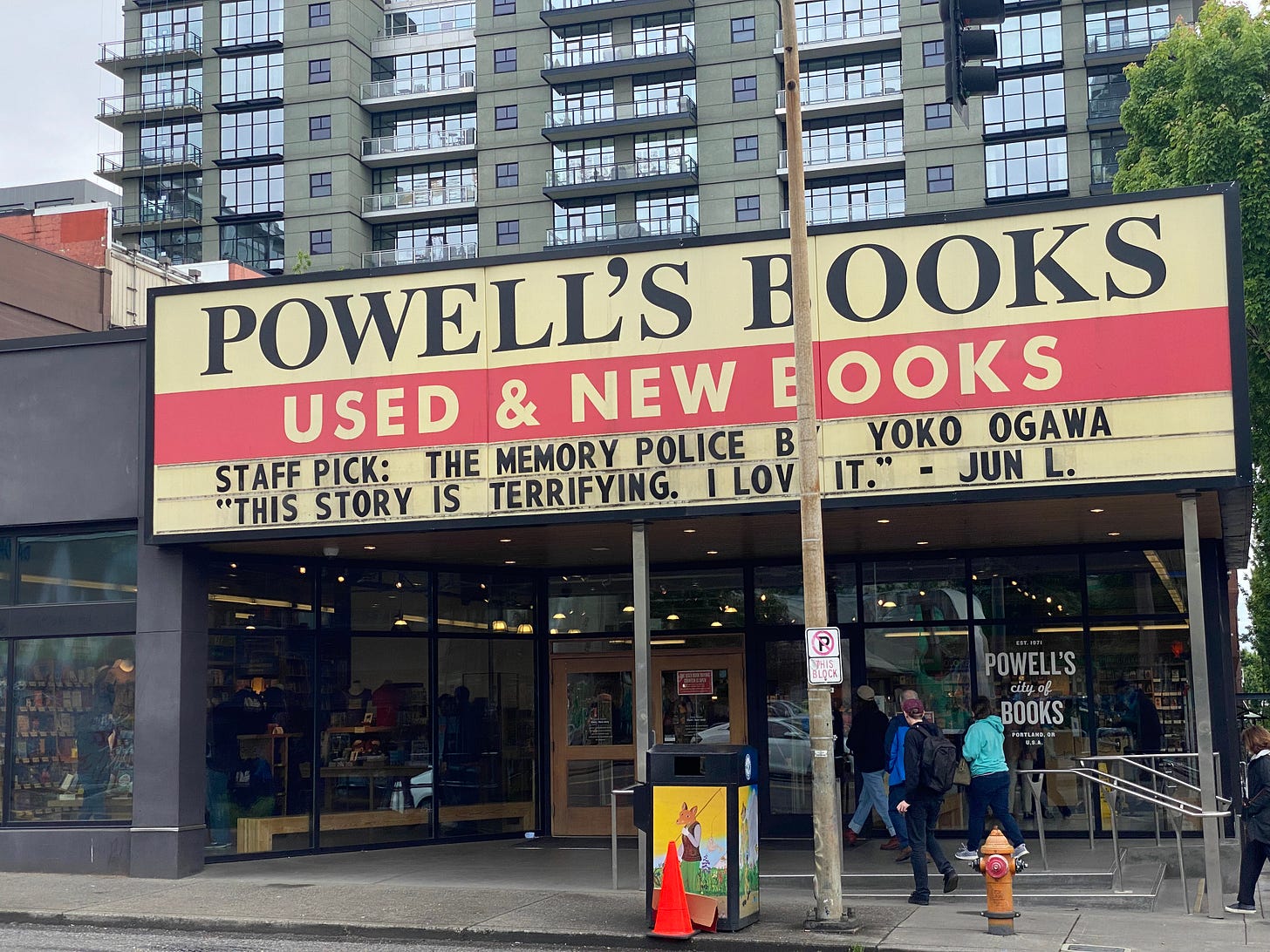

By Powell’s, my father meant Powell’s City of Books, the mega-bookstore at the heart of Portland, Oregon. Powell’s is a gargantuan establishment comprising four stories and 68,000 square feet, packed to the brim with every book imaginable for every different take on every different topic.

Throughout my early teen years, Powell’s became a minor obsession of mine, though I didn’t get an opportunity to see it until my junior year of high school when I was in town for a college tour. I remember seeing the massive building when walking downtown, feeling the hype build, and then being suddenly underwhelmed when I finally walked in the door. Powell’s was just books, tons and tons and tons of books, all organized, tagged, and laid out so that you could easily find any title, no hassle required. I wanted to love Powell’s, but somehow, the architecture of the building itself made it almost impossible to appreciate what was on offer. I left feeling that I had somehow missed the point and that I would need a return visit to really discover what made Powell’s City of Books such a special place.

Still, no matter how many times I visited Powell’s, living in Portland as an adult, the experience was never any less dissatisfying.

On the surface, I suppose, it’s fairly easy to understand what’s wrong with Powell’s. It’s just too big. There is no sense of selectivity. It’s just like walking through the Amazon catalog. But in a different way, I felt that there was something altogether more twisted about the way Powell’s was designed, the way that it took something like a used bookstore, a place with so much magic, and transformed it into a bland consumerist hipster project.

Powell’s City of Books is actually a fairly interesting building in its own right. Having been the product of generations of expansion from the Powell family, who owned the franchise and built its headquarters in Portland, Oregon, the store was slowly grown through a series of expansions and renovations that gave the establishment an irregular arrangement like some strange chimera pieced together from different animals. As such, even the process of buying a book at Powell’s felt disjointed, even though every one of my trips to the store followed the exact same pattern.

First, one would walk into the store at one of two entrances on either side of the building (each looking oddly identical) and gander at the newest recommendations and paraphernalia for the modern urban book-reader lifestyle. Then, provided a visitor could snap themselves out of their consumerist stupor, they would choose an area of Powell’s (coded by room color) that corresponded to their preferred genre and travel to it via elevator or stairway. However, instead of a standard section dedicated to a subject, the visitor would enter the colored room and find an entire genre-specific bookstore, so large that it would be impossible to get a understanding of the selection or locate anything interesting.

Powell’s makes it impossible to find what books might be like Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings just by looking at what other titles are located in its vicinity because inevitably, you are stuck looking at an entire shelf of books by Tolkien and about Tolkien across various editions. If you look for Tolkien, Tolkien is all you will find, and no happy accidents need occur. Therefore, a visitor can only find something interesting and new by taking random stabs at the collection, usually only locating a book that he already knew he wanted. In fact, one had a better chance of discovering an interesting book bag than a novel peiece of literature or non-fiction. And I imagine that very few people walk out of Powell’s with a book that couldn’t have been given to them by their Amazon recommendations page.

In my own experience visiting the store, I remember the books of Powell’s much less than I remember sitting in Powell’s in-store cafe talking about the books that I had just purchased. In fact, the cafe and the conversations there seemed to contain the essence of the bookstore’s spirit. Everyone walked in, thinking that they were there to discuss something different, but then always seemed to say the exact same things.

Here my friends and I were, sitting in the middle of the largest bookstore in the world, discussing ideas and stories. Yet, the novelty we were seeking was entirely fake. And everything was weighed down by an indestructible sense of Deja Vu. The ideas and stories discussed were always the same, as was the smug satisfaction of the Millennial “Did you read it?” type conversations that underlined our experience there.

We all wanted to pretend that we had already read the really important books that made us educated individuals, just like we all wanted to pretend that the books we had just bought would be similarly life-changing. But nothing would ever really change, and we would be back the next time to talk about the same set of popular safe-edgy ideas with the same pretentious attitudes, never being affected by any of the words written in Powell’s voluminous collections, even though it comprised the wisdom of the world.

Powell’s City of Books was like a funnel that took in the breath of all human knowledge, ground it into consumerist book slop, and then converted it into hipster babble. Powell’s City of Books was “Media Literacy” incarnate.

In fairness, I can’t say that I never purchased a book at Powell’s that deeply affected me. In fact, I can still remember the books that I originally purchased when visiting the store for the first time as a 17-year-old. The first was a selection of essays by Argentinian literary critic Jorge Luis Borges, which had been recommended to me by a friend from my high school math club. The second was a novel that was the source material for one of my favorite Sean Connery movies, Umberto Ecco’s The Name of the Rose. At the time, the selections seemed entirely disconnected. It wasn’t until later that I picked up an ironic common thread leading through each author’s thoughts and back into the setting where I had initially purchased the titles.

For those unfamiliar, Borges's essays, while quite varied, are highlighted by one particularly famous didactic short story, The Library of Babel. However, perhaps the term “short story” is a misnomer since Borges's story isn’t at all narrative; his writing simply describes the existence of an infinite library that contains not just every book ever written but every book that ever COULD be written. Stretching into eternity from bottom to top in layers like Dante’s description of purgatory, the infinite library is inhabited by an indefinite number of immortal monks who travel freely up and down the levels, browse its books, and try to determine what is “truth.”

Beyond the initial concept of the library, Borges's essay explores the challenges monks face trying to search for meaning inside a space with such an unbounded range of information and with such a minimal set of experiences.

Perhaps the goal of the monks might be to locate the ultimate guide to finding all other truths, a map of the library that would be a Rosetta stone for understanding their world. But how might one find the perfect map of an infinite library inside an infinite library? Moreover, how could one verify its contents? In this pattern, Borges's conjecture descends into infinite regress, an unsolvable conundrum that folds back in on itself

On my own reading, Borges's library seemed a direct callback to the proof of Kurt Godel’s famous Incompleteness theorem, which dispelled Russel and Whitehead’s project of indexing all possible mathematical axioms. However, I am not sure that Borges intended his work to be such an on-the-nose analogy and probably just wanted his essay to be a general thought experiment that made people think about the nature of information in a highly abstract and self-referential way.

On the other hand, authorial intent was much easier to read in The Name of the Rose, where Umberto Eco explored a surprisingly similar theme in his story of two Franciscan friar’s journey to an ancient library located inside a Benedictine Abbey.

Though the connection did not occur to me as a teenager, it’s hard to imagine how Eco didn’t intend his novel to be a realistic counter-note to Borges’s famous abstract essay. Like The Library of Babel, the Franciscan protagonists in The Name of the Rose find themselves as guests at a mysterious 14th-century Italian abbey containing an even more mysterious labyrinthine library. Among the protagonists’ motives for visiting the abbey is to locate one particular book from far antiquity, considered by many of the more conservative religious leaders to be unwholesome.

The heroes’ quest grows ever more perilous as it seems that every monk who finds and reads the forbidden tome mysteriously dies shortly afterward. Perhaps foul play is involved? Or maybe it is divine retribution indicating that the infamous book contains knowledge God does not want mankind to know?

I am not sure if I need to offer a spoiler alert for a 40-year-old novel, but the author ultimately locates the culpability for the murders in one austere, world-hating monk who has smeared the pages of the book with poison, therefore causing death to anyone curious enough to read it. The ultimate motivation of the deadly trap is to obscure the contents of the book, Aristotle’s long-lost treatise on humor, a work that the maniac believes will undermine the necessary separation between low bodily pleasure and the higher spiritual calling of intellect and holiness.

Ultimately, the author’s point came down to a very on-the-nose criticism of the Medieval separation of bodily and spiritual joy, an idea that Eco felt had poisoned much of Western thinking throughout antiquity and modernity.

When I read the book as a teenager, the author’s message seemed well made enough. And the plot, whether read on the page or seen on the screen, is still compelling suspense to this day. However, as my thoughts returned to the mysterious library and the deadly book at its center over the years, I began to feel that Eco’s conclusion seemed fundamentally anti-climactic.

Like a young Tolkien thinking that Shakespeare missed an opportunity in Macbeth when the forest did not literally come to assail the castle, I gradually began to feel that Eco had missed a much more important theme when he made the secret of the deadly book come down to cyanide-laced pages. Naturally, Eco wanted The Name of the Rose to be realistic. But wouldn’t it have been better if the actual wrath of God had killed the men who had polluted their minds with blasphemy? Better yet, what if the book’s contents were just so vile that they corroded the human mind, both spiritually and physically?

After all, the idea of a “death note” was a perennial concept in the medieval imagination, that horrible series of sounds or words that would drive a man to ruin if he were unlucky enough to experience them, just like Robert W. Chambers’s The King in Yellow.

In fact, of all iterations of the “death note” theme, The King in Yellow seemed like just the type of book that should be hidden in the recesses of a mysterious labyrinthine library, absolutely prohibited yet somehow essential to preserve.

Most commonly in modern fiction, this type of lethal “information hazard” is described in oblique technical terms as if the mind was being overwhelmed or hacked, the lethal data causing death because it killed the brain like a short-circuit or burst it like a balloon. The King in Yellow breaks from this form by describing its eponymous play like it was a mystical door to a greater reality, causing death not through some physical reaction but through exposure to a new perspective on the universe which, while true, was so horrifyingly perverse that it would cause death and insanity to anyone who experienced it.

Chambers executed this perception magnificently by having his fictional death note appear as a play in two acts, the eponymous King in Yellow. The first act, which might be read or witnessed without harm, describes a surreal dialogue between three masked characters (Cassilda, Camilla, and “The Stranger”) who are waiting for a “King in Yellow” coming from a city alluded to as “Carcosa”. The second act presumably describes the King’s arrival, although this can never be confirmed since whoever reads (or witnesses) that part of the play goes mad and soon thereafter meets their doom.

The imagery of The King in Yellow pointed directly to something almost cosmic in its magnitude: the limits of man’s knowledge, both physically and teleologically. Mankind’s mind was designed to move in a certain way and in certain directions, not embrace all of existence. Furthermore, there were some dark paths that could only be followed so far before a thinker embraced his own doom. There was a line of no return that could not be crossed, and that line lay between the King in Yellow’s first act and its second.

For my younger self, this concept of a “death note” seemed fanciful but strangely plausible. After all, information did change people, many times for the worse. Wouldn’t it seem almost logical for there to be an end-point for this badness, an absolute worst book imaginable. A book that possessed a perversity not measured in the trueness of the information but in terms of its qualitative impact on the human psyche?

In fact, the prospect seemed even more interesting when I superimposed the notion on Borge’s Library of Babel and the monks searching for truth in an infinite sea of information. Certainly, the goal of the monks was to find the truth, the perfect map of the library, discarding all counterfeits. However, wasn’t there the dark possibility of another unstated danger, the “info hazard” or the death note that might also exist inside the library? Just as a monk might discover the perfect map of the library and its various approximations, they might also find The King in Yellow or some similar book that would corrupt or destroy them.

And the consequences of absorbing such bad information would not simply be limited to death or madness. In fact, it might be a much more prosaic form of corruption. For instance, Borges assumed his monks were all perfect seekers of truth, concerned with little else than finding good, factual books in the infinite library. But could a monk’s disposition towards truth be modified by information found inside the library? Could a monk be convinced to pursue falseness rather than truth, or lie to his brothers, or horde information and spread falsehood to everyone else? And if the bad books were circulated inside the community of monks generally, the harm caused might be incalculable such that the entire collective mission to find truth might be capsized. Borges’ infinite library was more perilous than the author initially imagined.

At some point, later in my college years, I remember becoming fascinated with the process of human discernment of information. Altogether, I had come to understand that the educational experience itself was something of an artificial conveyor belt of sorts that exposed you to some types of information and not others. On the surface, college educators claimed to be just exposing students to “facts”, but this was obviously not the case once one scratched the surface. The education was decisively and intentionally pointed toward some ideas and away from others.

Was the direction of our education designed to save us from moral corruption? Or had it been formed from our teacher’s own corruption in turn? Could the knowledge we were receiving actually be harmful? Might the values we were learning direct our generation into an existential dead end?

The question was vexing, not least because, being somewhat knowledgeable about older thought at the time, it was apparent that modern educators were trying to steer their students directly toward a set of behaviors that previous generations of educators had attempted to guard against. The old world’s “syllabus of errors” was the new order’s recommended reading list, and if there were any genuine “info hazards,” we had been set right on a collision course.

But how could we figure out if modern education was bad? And what would it even mean to be corrupted by a world view? Wasn’t it all just information?

I supposed, perhaps, that a point of view could be corrupting if it encouraged selfishness and pride while discouraging heroism and courage, if it made people both weaker and less spiritually generative. I also supposed that a worldview might be corrupting if it slowly drove its adherents mad, as in Chamber’s fictional play. And there did seem to be many people in my generation going mad along some ideological line or the other.

Still, while the psychologically corrosive properties of the modern progressive worldview were on my horizon, what struck me more immediately was this different way of thinking about ideas.

Initially, as a very modern person, I was encouraged to think about information in binary, as either true or false, which, if one were allowed to think in shades of gray, could be conceptualized as a single-dimension problem contained in the question: “How true or how false is this information?”.

However, once we expanded the description of data to include the question of corruption and enlightenment, a new dimension was unlocked. Now, for each piece of knowledge, a thinker might ask both “Is this true?” and “Is this uplifting?” with the interaction between the two standards of value creating an implicit coordinate system with four quadrants separating the different forms of human knowledge.

When first speculating on this subject, I drew an illustration in my notebook to represent the conflict, which I reproduce here digitally in higher resolution.

For those without access to images, the chart outlines the space of human knowledge framed along two axes, the first axis being “Truth vs. Falseness” and the second axis being “Uplifting vs. Corrupting.” Subsequently, the plane is split into four quadrants, described as follows:

Quadrant One: This is the world of uplifting truths and enlightening wisdom. It is knowledge in the way that knowledge is supposed to work. It is accurate information that, when realized, makes one stronger, more just, more holy, and to want what is good. This is the truth that sets us free. This quadrant is represented imagistically by the Angelic Messenger.

Quadrant Two: This is the space of uplifting falsehoods, the things that aren’t true and maybe outright deceptive but that nevertheless lead a seeker in good directions and towards happy accidents. These are the white lies, the good-hearted jokes, the moral fantasies, and the myths and fables that contain within them something more profound, even if every word is not factual. This quadrant is represented imagistically by the (holy) fool.

Quadrant Three: This is the area of the denigrating falsehoods. The black lies which deceive cruelly and lead to ruination. The vicious fictions that bring people low and the chaos that burns all meaning to the ground. There is nothing good to be found in this quadrant. It is represented imagistically by the great deceiver.

Quadrant Four: This is perhaps the most puzzling quadrant, the region of corrupting truths. The types of information that, while true, lead someone in a bad direction morally, perhaps ultimately to their own ruination. This is the space of info-hazards and death notes, the location of The King in Yellow. It is represented imagistically by the Sphinx in honor of the monster that destroyed King Oedipus with the truth, even after he had defeated her riddle.

After drawing out this diagram, I found it very hard not to think about the question of knowledge differently. Certainly, the distinction, as expressed along the main diagonal, was more or less what I expected. This was the perspective on knowledge that I had been raised to understand: truth is goodness, falsehood is evil, and by always preferring the former, we could be assured of our own righteous intentions, as all people from academic families implicitly believe.

However, things were more complicated across the alternative diagonal where a necessary trade-off was occurring: the sphinx offering corrupting truth versus the fool providing uplifting myths. Like all trade-offs between two very different things, it seemed, at first, that the distinction might be dependent on the circumstances, with a preference for truth being better in some situations and a preference for moral uplift being better in others. Yet the more I thought about it, the more the difference between the two quadrants became stark and unmistakable.

The fool, even though he was deceived, could never cause harm; his falsehoods always would lead to virtuous outcomes, and his lies were always noble. And though he taught things that were not true, his teaching would only ever result in the love of truth itself. So, under these circumstances, could the moral jester not but be holy in some way? Could he not be just some angel otherwise forced to disguise his nature in the name of something greater?

Meanwhile, the Sphinx, though she spoke only facts, was the cruelest demon of the pit. She led men to the truth, but only those poisonous truths and asymmetries that wrecked their minds and twisted their souls. However, unlike her other demonic counterparts, the Sphinx’s work would be almost impossible to detect since her words conformed to reality as it was seen. And there wasn’t even any consolation to the truth she provided because the corruption that accompanied such knowledge would inevitably degrade any virtuous pursuit that it was intended to support, including the pursuit of truth itself.

To be brought to perdition and led there, every step of the way, by knowledge that is “true” would be the most horrific fate imaginable, and the sphinx brought this horrible fate upon men with the countenance of a smiling face and unfeeling eyes.

This spiritual corruption is the ultimate risk in all endeavors of the mind. No matter what an intellectual might say about his unrestricted exploration of knowledge, there always looms the danger that he might be seduced into a perspective that ruins his own curiosity and love of truth. This was the true “info-hazard”, the intellectual version of The King in Yellow, the poison pill for civilization itself. because once you pass a certain threshold and become convinced at a spiritual level that life has no meaning and that truth can be bent to the purposes of one’s ego, it is difficult, in fact almost impossible, to find your way back towards sanity and health.

In this light, I could never look at traditional regimes of censorship in the same way again, and the smug George-Carlin libertarian perspective on “free inquiry” never hit with the same weight. Certainly, if true spiritual corruption is possible, then all efforts in education and literature should be directed against this peril, as many in the old world had directed their efforts against heresy. Since any one misstep might lead to the ruination of the world and the shattering of the civilizational order, society had to be vigilant and adamant to not feed spiritual poison to new generations.

And didn’t the modern progressive world also agree with this concern on some level?

Liberal educators certainly had their own understanding of info-hazards. But for the modern progressive, the concept of corrupting ideas was only ever political. You didn’t want to read bad books because you might become a “Republican” or an “Ayn Rand fanatic” or, in the worst case scenario, a “Nahtzee”. But might not exposure to bad ideas also just make a person evil or lazy or self-destructive? Shouldn’t progressive education, if it was truly conformed to the interests of humanity, point its students in the direction of an ordinary moral life?

And if there was any cohort who ever needed direction to an ordinary moral life, it was the Millennial progressives. Not a Republican, objectivist, or “Natzhee” among them, all adherants to some variation of leftist ideology, and all being taught the correct opinions, they were, nevertheless, being devoured by their lifestyles and ideology. Almost all of my friends were suffering from some form of poor mental-health and were on anti-depressants; most couldn’t form stable relationships, and even among those who had “made it,” there was a strange listlessness in everything that they did.

Furthermore, it seemed that whatever worldview these young progressives had absorbed from college made it almost impossible for them to explore any new ideas outside their pre-defined leftist understanding of the universe. Any ideas from outside this 20th-century progressive perspective were regarded with extreme suspicion, and the more grounded an idea seemed on paper, the less willing liberal Millennials were to entertain it in the slightest.

I remember my time talking about ideas in Powell’s City of Books. Every one of us there seemed radically intellectually incomplete, yet we were also supremely uninterested in the possibility contained in the books that surrounded us. We had found ourselves in the closest approximation of Borges’s infinite library. A world of possibility lay before us. Yet, there wasn’t any hope that we might find a book that could give us the guidance we so desperately needed. There wasn’t even the fear that we might stumble upon a truly terrible book and become spiritually corrupted by its contents.

Shouldn’t we be in a state of awe at the prospect of new knowledge, for better or for worse? Could we not understand that the books here might lead to enlightenment and a radically different life? Or, alternatively, might we not at least fear that some piece of information might damage our perspectives on the world? Wasn’t there a chance that any one of us might inadvertently encounter an information hazard and become spiritually corrupted?

And then a dark thought occurred to me. Perhaps we already had.

My generation couldn’t desire spiritual truth, much less fear spiritual corruption, because it had already been corrupted. It was following the cruel and inevitable logic of the Sphinx, moving from meaningless fact to meaningless fact, until the desire to discover ultimate goodness drained away entirely, and nothing but chaos and madness remained left behind.

And it wasn’t just my progressive friends who had been corrupted; it was all of society; the corruption was even present in my own understanding of truth, goodness, and beauty, which, even if my desire for spirituality remained, had to be viewed through a dark glass and justified by numbers and meaningless performative apologetic arguments.

What was the nature of this modern info-hazard? What was the threshold that we had crossed? The modern disease has a thousand names: “Godlessness”, “egoism”, “materialism”, “spiritual pride”, and “Chaos”.

But regardless of the name of the malady, it had thoroughly penetrated our modern collective consciousness. We had crossed a line and were now in free fall.The cancer had already set in. The tumor had metastasized. Modernity was complete. If the path were followed to its conclusion, it would lead only to ruination.

To find any way back to sanity would require something heroic and historical, and even with such a herculean exertion, only God could save our civilization and our souls.

In Decline of the West, Spengler talks about a point in civilization, the winter stage, when the people who inhabit a society start walking away from the cultural and scientific fruits that were produced during its golden age. For the longest time, even before reading Spengler, I found this prognosis puzzling. Spengler’s sentiment seemed both deterministic and irrational. Certainly, decline couldn’t be inevitable.

Why couldn’t the fall of civilization just be “stepped over” as Hari Seldon attempted in Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series? Moreover, at what stage could people knowingly walk away from knowledge and technique? At what moment would you decide that you know too much and need to go backward? At what point could you discard the knowledge that your ancestors had labored to learn and preserve?

These were difficult questions to answer inside the progressive understanding of history, but they became easy enough to grasp if one stepped outside of it. People might rightly walk away from civilization or try to forget knowledge if they felt that the civilization or knowledge in question was poisonous.

Spengler describes the process of civilizational collapse as fundamentally organic. While not mindless entirely, there is a kind of grim determinism to his process, like the changing of the seasons or the lifecycle of a moth. Human agency and decision-making do not really play a role in the pattern of Spengler’s broad historical form.

Still, I find myself wondering, increasingly in these later years, if collective agency doesn’t play a critical part in the natural dying process of culture. Perhaps the people who walked away from the past glories of the older civilization were cutting their losses, separating themselves from something that was dragging them down. They were trying to spit out a poison pill that had been swallowed centuries back and that was now drowning their humanity and spirit. The only way to break from this insidious pattern was an act of cultural purging, walking away from much of what had come before them.

There is a point in time when humanity seeks forgetfulness as an asset. There is a period of history where parts of the past must become radically indecipherable because to stare constantly into the face of its mistakes is paralyzing. The bonds must be broken; the structures must be shattered like a potter’s vessel; and whatever new life and order that is to be found must be found by moving outwards and away from whatever harm had been wrought by the errors of the old world.

This insight might be just what the late Greeks grasped when they described the paradise of Elysium lying just beyond the river Lethe, the eternal spring of forgetfulness, where the blessed spirits had to leave behind the memories of their past lives to achieve bliss. Without a deeper concept of salvation, how could it be otherwise? How could souls, with all of their sins, obtain true happiness with their past memories still echoing in their beings? Would they not be like the dead as Homer described them, slaves to the last moments of their lives, repeating the patterns they had known in life endlessly, like a computer program caught in an interminable loop?

Certainly, even as a Christian who does believe in a more wholistic form of redemption, I can sympathize.

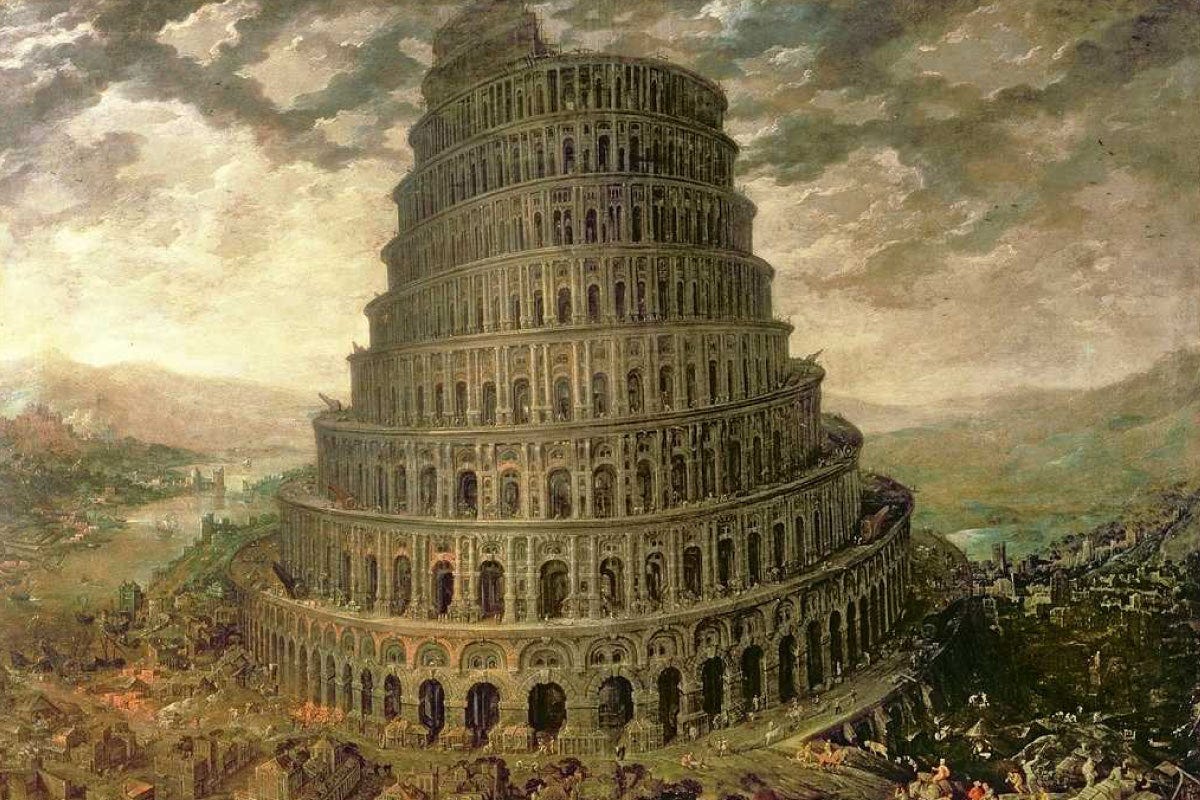

And perhaps human collectives also find themselves in similar predicaments. Certainly, just such an example remains in the book of Genesis when God crushes the tower to heaven not with bolts of lightning but with incoherence, the separation of tongues, and the breakdown of literacy and communication. Here, Divinity directly crushes pride and terminates its memetic poison by striking at the head of the serpent.

The first pretense of human civilization was to contain infinity through technique, a direct antecedent of our modern Faustian desire to contain all knowledge of the universe and, by doing so, chain heaven and its infinite horizons to mankind’s aspirations. But, as always, the finite and organic cannot contain the infinite, and man’s pretension invites his own self-destruction. To be saved, man must be humbled, pushed through the eye of the needle, and returned to the ground from which he was formed.

The language of iniquity must be lost to the people because the separation of the people from their past is a necessary first step to their redemption. And even if there were an opportunity to forgo this tribulation and cling to the comforts of ancient knowledge and technique, wise people would not take it. The only way out is through, and the way through involves letting go of what we once thought we knew.

These are the blessings of Babel. That forgetfulness can, at times, be necessary. That illiteracy of a certain variety might be a boon. Because unless we can be like children, blithely pursuing the good without the weight of pride, the ambition towards knowledge itself will crush the portal to the divine, drown out the voice of God, and leave mankind isolated in a sea of Chaos, devoid of meaning.

This without a doubt belongs in the hall of fame. I don't think I can add anything to it with my comments, but I'll attempt it anyway.

A sense of dread rose in me as I read. Is the poison pill long gone, down our gullet and into the bloodstream? I certainly feel that way when I think about whether there is a way out of our predicament using our own faculties. We are along for the ride down without agency and we are the only ones with our eyes open. Knowing often feels like an additional burden and nothing more. It only helps if one gets the urge to grasp onto simple, humble faith in the God who invites us to die in faith and be reborn, physically and spiritually.

I certainly think that there are things that break something within us if we knew about them. That's how I feel when I get a glimpse of the Grooming Scandal in my feed, or descriptions of the most heinous shit in the dark web. They repel one away with a gut-wrenching sensation, but there is still a sick curiosity that coaxes one to look in. Porn can break something within a young mind so fundamentally that a person might struggle with real intimacy for the rest of their lives. In hindsight I wish I would have had someone to warn and protect me in my youth from the internet specifically. There is a portal to hell in every pocket.

There is a right way to learn about the evils of the world that inoculates one to its influence, and a wrong way that plunges one in entirely. Evil, after all, thrives in ignorance, and can rob a good person of hope if one is overexposed.

These thoughts are the ones I could put into somewhat coherent words. I had many more that refused to coalesce, and that's the mark of a great piece of writing!

From Book Tok to the Tower of Babel. What a journey! And there’s more! Bring it!

I definitely can relate with having professors who seemed to shun certain material and pushed what amounted to pretentious bloviation. The overall effect, beyond making us “critical thinkers” or whatever, was to make reading boring by dehumanizing and emptying the content.

I think that might be why the mega bookstore never really got to you. It served a lifestyle and was mainly impersonal in its function. Reading was secondary. More important was being part of the book scene with your fellow hipsters.

I guess I could think of worse things in this world. But this seems to be the opposite cultural result of what the bookstore people were probably hoping for.