For those who are opening this letter in anticipation of the second part of my longer essay series, I am sorry to disappoint, but this is not it.

Instead, today, I want to address some recent criticism written by my friend Alexandru Constantin in response to one of my recent podcasts on modern culture and degeneration.

As someone who is otherwise starved for discourse, I find this kind of friendly correspondence refreshing. Moreover, given that the topic directly relates to the series of articles I am currently writing, Constantin’s criticism seemed like a good opportunity to explore a common criticism and, in the process, showcase a productive dialectic.

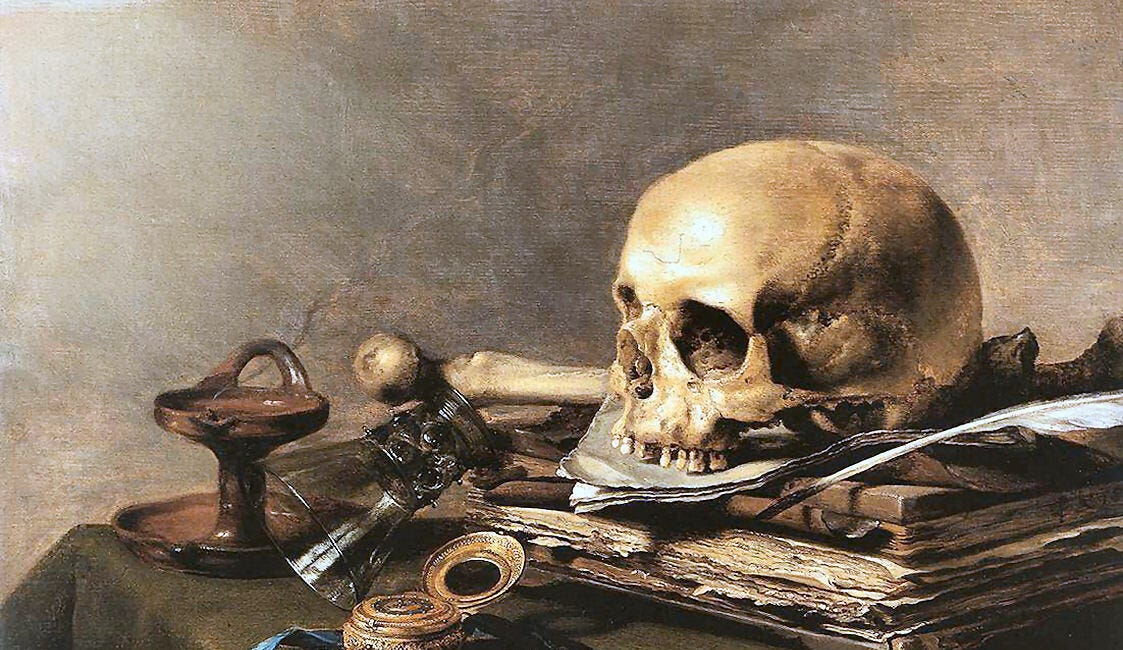

To break down our ongoing controversy for a new reader, on a recent podcast, I explored the phenomenon of mass cultural decline in the last half-century and conjectured that this observable degeneration was the direct result of our culture's separation from its core spiritual purpose. As such, what remains of culture after it has lost its teleological motivation is a series of iterations that increasingly discard meaning in favor of consumeristic "lifestyle" products, a.k.a. “slopification.”

As an extension of this thesis, I pointed to trends in recent pop culture, especially in the past 20 years, which I would argue have shown a decline in relevance and spirit even in situations where the technical quality has improved (see the recent work of Robert Eggers for an example).

But is this the only explanation for the phenomenon of cultural decline?

Alexandru Constantin thinks that I have missed the mark with my diagnosis and provides an apt (but anticipated) critique of my thesis in a recent essay, which made the case that the problem is not “slopification” but “infantilization.”

To summarize Constantin's critique as best I can, the author contends that my description of “slopification” is overstated. What is going on is not a general decline in the spiritual relevance of the culture but a kind of collective arrested development on the part of consumers and cultural critics like myself. When people like me look at the modern texts on offer and are struck by a feeling of dejection, what we are experiencing is not a genuine decline in these products sp’ spiritual relevance but rather a feeling of nostalgia and generational mismatch.

The problem is not that the Marvel Cinematic Universe is necessarily worse than Peter Jackson's Lord of the Rings or that Taylor Swift is necessarily worse than Nirvana or Soundgarden. The problem is that adults are trying to consume media otherwise designed for younger people and are predictably disappointed when it doesn’t provide the deep relevance they seek.

In fact, the types of media that internet critics usually focus on (be they action movies, music, literature, and games) are really just for children. They were never meant to express deep themes for adults. Moreover, the meaning that adults expect to find in these products is simply the result of nostalgia that was obtained in youth and cannot, therefore, be relived as an adult. We experience the sensation of cultural decline because we have “infantilized” ourselves. Therefore, it doesn't really make sense for an older person like me to criticize the quality of modern pop-icons, role-playing games, or the latest Star Wars movies because they are, in a fundamental way, "Not for me."

I imagine here that some of my readers will pick up on Constantin's phrase “not for (you)” because the term has become something of a cliche in the age of woke media, where any and all audience disapprobation against the latest progressive fiasco is portrayed as a category error and a sign that the critics themselves are overgrown man-children trying to bring overblown criticism to media designed for children or some other protected minority group. Under these circumstances, it might be a little too easy for readers to dismiss Constantin's thesis about the “infantilization” of modern consumers, even though I think there is a lot to be understood from his argument, at least in its steelman form.

Examined broadly, Constantin is correct in observing that much of our modern dissatisfaction is driven by “infantilization” on the part of consumers. Moreover, while the assertion that adults should not offer deep criticisms of pop culture is silly, there is the inescapable reality that many modern people look to pop culture to obtain a type of meaning that the medium is fundamentally incapable of providing.

I would agree with Constantin that “infantilization” is a real phenomenon. However, at the same time, it seems obvious (to me, at least) that this phenomenon of cultural immaturity is a second-order effect of our broader spiritual degeneration. Moreover, although infantilization might be confused with the more large-scale “slopification” of civilization, the two phenomena are clearly distinct when one examines things closely. The former is (almost) always the consequence of the latter.

Leaving aside some mistakes Constantin made in restating my original position (I am actually rather fond of Warhol, much less his modern imitators), I think we might be able to discern the difference between “infantilization” and “slopification” by looking at the author's own examples, which are divided into three general categories: nerdy board games, movies, and music.

First, on the question of nerdy board games, Constantin makes a strong case that these types of pastimes are, fundamentally, adolescent pursuits, and the fact that we are looking to them at all as adults is an indication that our own lives have become horribly “infantilized.” To illustrate, Constantin compares such forms of entertainment to his childhood teddy bear, which, though it contains much sentimental value, must be put away in the closet, at least until it can be bequeathed to a child of appropriate age. Any attempt to draw the same meaning out of the object as an adult is a foolish pursuit that might only result in frustration, melancholy, and extended arrested development.

Constantin’s example of nerd culture is compelling. And, while I have to resist making the pedantic point that wargaming and role-playing were developed as adult hobbies, it is indisputable that they have become part of the adolescent culture in the modern world. Many, if not most, hardcore fans of nerd culture have a deeply unhealthy relationship with their consumer fascinations, to the point that they are used as surrogate adult identities. However, looking beyond the cultural disaster of adults becoming fixated on distinctly juvenile entertainment, it's hard to notice that there is something much deeper going on in modern "nerd culture", especially if you talk to the people who dedicate the lion’s share of their free time to these pursuits.

As it turns out, a different picture emerges once one actually talks to the young men obsessed with these types of hobbies. Almost invariably, these guys are looking for things in their hobbies that they have every right to desire but which modern society no longer provides. These are things like a friendly but adversarial way to compete with other men, a connection to a heroic tradition, a story that they can really feel is their own, and a feeling of spirituality (although nerds rarely mention this part). You might think that nerd hobbies are juvenile, but they are a surrogate response to replace an entire world of masculine cultural energy that used to exist in the West but is absent in the modern world.

Sure, maybe that 28-year-old seems “infantilized” when he looks for a symbol of masculinity in a plastic GW Space Marine. But, to be fair, where else is he going to look for that kind of ideal? Books? Movies? Music?

Once more, I don’t think you can tell the story of the “infantilization” of these types of men without describing how cultural decline (or “slopification”) cut off their avenues toward more mature media consumption. There has been a lot of cultural decline in the recent past, to the point where the arts and letters that once held the attention of bright young men are barely recognizable anymore.

From movies to television to books to music, the decline in the spiritual quality of our media is impossible to miss. Of course, I should admit that this decline is not uniform. There are exceptions, and some genres, like horror films, seem relatively untouched. Still, when you look at the types of kinds of media produced during the last two decades and compare them to the products of any equivalent length of time across the last two centuries, then the difference is unmistakable, especially when it comes to genres of media that might inspire young men towards embracing their adulthood.

Case in point, we might examine the genre of epic Science Fiction movies, as Constantin does in his exploration of Star Wars and its prequels. Perhaps unsurprisingly, I remember having a very similar experience to the author, first seeing The Phantom Menace in theaters, utterly detesting it, and then slowly coming to terms with the movie after seeing a young neighborhood kid falling in love with the prequels. Sure enough, there was an element of maturity that my 13-year-old self learned when I realized that the new Star Wars wasn’t “for me.” Moreover, further conversations with younger Millennials over the years have taught me that perhaps the prequels do indeed have their redeeming points. Still, despite whatever legitimate defense can be made of the prequel films, The Phantom Menace still represents the loss of something, and these younger guys don’t fully understand what was taken from them.

To account for my own age, as Constantin insists, I first saw the original Star Wars on VHS around the age of 7. Watching the film, I, like most children, was enthralled by the movie’s stunning special effects, action-adventure plot-line, and science fiction settings. However, it wasn’t these qualities that made Star Wars a transformative experience. After all, in the early 1990s, there was a new special effects action blockbuster almost every summer, and as children, we had no shortage of science fiction entertainment targeted at us, from Transformers to He-man to Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Still, for some reason, even as a child, I knew that Star Wars was special and the film had something to teach me.

Why did I think that?

Well, for one, Adults liked Star Wars. Many of my relatives and teachers had seen the original films in theaters and had very much enjoyed them. Moreover, every time that I re-watched the movies, it seemed to unlock something different. One review of The Empire Strikes Back triggered a conversation about pacifism and warrior virtue with my mother. Yet another viewing of the trilogy made me aware of the influence of Japanese cinema on George Lucas, leading me, in turn, to discover the films of Akira Kurosawa at a young age. And, just before the release of Episode One, I remember seeing an interview with Joseph Campbell that featured references to the original Star Wars, prompting me to pick up his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces, even though I don't remember learning much reading it.

Star Wars wasn't supposed to be kids' entertainment; at least, it didn't seem that way when I was a kid. Star Wars was supposed to be a portal to something more significant. Perhaps the young Dave Greene was being presumptuous walking into the theater in 1999 to watch A Phantom Menace and expecting something with philosophical substance, but was I so out of line for wanting a movie that could plausibly be enjoyed by people over the age of 12? My mother had enjoyed the originals in the theater when she was well over 25.

Indeed, Star Wars was for kids. But entertainment for kids isn't always just for kids. I know this much from my rather limited experience as a father. When I watch Snow White or Pinocchio or My Neighbor Totoro with my son, I understand that these movies are something special. The experience is qualitatively different than watching something like Paw Patrol or Vegi-tales. And while I thoroughly enjoyed taking my son to see The Mario Movie, just as I remember enjoying The Transformers Movie with my father 30 years earlier, these movies are both “slop.” They are low effort. They are standardized. They open no doors. They provide no keys. They have no meaning outside of the specific group of people they were meant to entertain.

By contrast, from Gilgamesh to The Odyssey to Lord of the Rings, stories of heroism always appeal to children, even though they are not designed exclusively for those children. And here, there is a crucial wisdom that 20th-century pop culture has obscured. The songs and stories that bring passion to youth are not supposed to silo the generations, separating father from son behind walls of mutual incomprehension. Quite the contrary, the fables and folkways that really matter are the ones that unify the generations and point both young people and old in the direction of common truths and hopes that transcend the force of time.

That's what masterpieces like Tolkien's The Hobbit and Lewis's The Chronicles of Narnia did. And that's what we thought Star Wars was going to do. It was going to be our own generation’s Lord of the Rings, a timeless song that we could take into adulthood as an inspiration and connection to something larger than ourselves. That was presumptuous, to be sure, but still enough reason to be disappointed when we discovered, slowly, that Star Wars was just another toy destined to be discarded after childhood and remembered in adulthood only for the purposes of futile nostalgia.

A text’s lack of intergenerational appeal is a symptom of its spiritual weakness, regardless of whether an adult decides to consume it. And, to the extent that adults and children are separated from a common set of experiences with media, our culture is impoverished.

I suppose this brings me around to Constantin's last example in popular music. Here, the author contests that there has been no real decline in the quality of music from the 1990s to the present day, focusing specifically on the genre of female singer-songwriters from Sheryl Crow and Madonna in the 1990s to Taylor Swift and Billie Elish in the current year.

On this point, I will plead a certain amount of ignorance. Not being a pop fan, I have no ability to evaluate Constantin’s claim. I appreciated Billie Elish’s Ocean Eyes, though I couldn’t tell you how it might match up in quality to something like Vanessa Carlson’s Thousand Miles. And while Madonna had a number of great earworms in her time, were they as sticky as Swift’s mega-sticky hit Shake It Off?

Really, I couldn’t say. Perhaps female singer-songwriters are one of those exceptional genres, like horror films, which are relatively unaffected by the cultural decline that we observe in almost all other types of media.

However, what I can say is that for the musical genres that I am familiar with, such as classic rock or shoe-gazer, it’s hard to find a modern equivalent

Who is this generation’s Nirvana?

This generation’s Sonic Youth?

This generation’s Cure or Joy Division?

Sure, I am old now, and old people don’t listen to new music. But my parents knew about Curt Cobain in the 1990s, even if they didn’t listen to him. And when I talk to younger guys and ask about their favorite rock bands, I usually get a list of older artists or puzzled shrugs.

Once more, it doesn’t feel like these younger kids have something new and different; they have just an absence, an absence that cuts deepest when it comes to those types of music that many men of my generation really felt meant something.

But perhaps even asking this question is a sign of my own “infantilization”. Perhaps I am wrong to be looking for a new Billy Corgan in 2024.

Was I misguided, thinking that something like Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness was trying to express a deep idea? Is even my current appreciation for this kind of music just an extension of my own arrested development, better consigned to the closet of old toys like my teddy bear from when I was a toddler?

We in the Millennial generation are the most pampered and immature cohort ever conceived. Maybe we are all trying to forestall the inevitable advent of real adulthood when we should ideally forgo all contemporary culture and dedicate our efforts to work, family, and the appreciation of ancient culture from centuries past.

I find Constantin’s perspective here provocative and challenging, but, for me, at least, it doesn't pass the smell test. It doesn’t match up with what I have seen in my own generation or those who have gone before us.

For instance, my parents certainly didn't have lives that were locked away from contemporary culture. Far from it. My liberal Boomer mother continued to enjoy many popular artists from her younger years, from Joni Mitchel to Fleetwood Mac, and complemented her music collection with a variety of new hits she discovered across the 80s and 90s. My father, on the other hand, while never being much of a non-classical music fan, still very much appreciated modern comedy and sitcoms. And both of my parents had no problem regularly finding movies that didn’t insult their intelligence, something almost unimaginable for my wife and me in the current year.

It was easy for people of my parent's generation to slide into an adult lifestyle because the mainstream culture was built for adults like them. Most radio and television shows spoke to their concerns. Wholesome family entertainment that reflected their values wasn’t rare. There were high-brow television programs that weren’t yet woke. And there was even a jazz and classical music scene that my parents frequented that wasn’t geriatric. And that’s not to mention my parents' true cultural passion: books.

In fact, books might be the best example of decline distinct from a medium that might be considered “infantilized” by nature. Books and literature were supposedly the cornerstone of all Western high culture, and their decline is undeniable at every level. Case in point, walk into any modern bookstore, and you will probably see something just like the scene that exists in the Barnes and Noble in my own metropolitan area: walls and walls of Chick Lit, Romance, Young Adult Fiction, and literal toys for teenagers with the “Literature” section consigned to a single shelf in the back of the store.

An Age of Illiteracy

Civilizational decline is anticlimactic. For all our contemporary fascination with collapse, degeneration’s lived experience is humiliatingly ordinary. It’s just a series of broken systems, ruined people, and things falling apart.

Moreover, unlike pop music or sci-fi movies, I am confident that my expectation for intellectually engaging books written within my lifetime is reasonable and not a projection born from childhood nostalgia. Bookstores weren’t always just toy stores selling slop to teenagers or adults with teenage reading habits, even though I half expect my progressive friends to tell me, any day now, that it has always been this way and that bookstores writ large aren’t actually “for me.”

Here, I can anticipate some pushback from Constantin. Naturally, the author might say that what I am describing as “slopification” is just the result of the “infantilization” of the consumers themselves. But here, it’s intuitively obvious to me that the causation goes in the opposite direction.

The story of decline in the 21st century was not (by-in-large) the story of a generation called by their civilization to embrace the heights of human achievement who then shrank from that duty because they didn’t want to put away their teddy bears (like Sebastian Flyte in Brideshead Revisited). Instead, the story of the 21st century is that of a civilization that could no longer understand its own aspirations, subsequently could not produce meaningful culture, and then marketed what remained as dumb entertainment to hide the otherwise obvious decline in its spiritual quality.

Talking to friends my own age, I have noticed that we share a common perception of the late 1990s and early 2000s. In that brief window, somewhere between when the last embers of grunge rock died and when the “The End of History” was lost in the flames of September 11th, America (and the West in general) faced a civilizational decision that it ultimately shirked.

To this point in history, the civilization that emerged after the Second World War followed a certain logic. Traditional morality was, in part, adopted from the old world to form the strictures that could hold society together. Meanwhile, elites encouraged a slow liberalization that gradually dismantled these old traditions and moral regulations, allowing an indefinite number of exceptions into the system without risking large-scale societal disruption.

Thus, the combination of a slow-rolling liberalizing reform paired with a steadily growing economy allowed most Western countries to experience the best of both tradition and revolution. There was a feeling that things would forever become more liberated while, at the same time, people would be connected to a common society with a common moral foundation. This was the comfortable American whiggishness of the late 20th century, that things always got better and freer without requiring any real sacrifice. The assumption was everywhere in the media of the 80s and 90s, and even though it didn’t really make any sense, we nevertheless believed in it anyway.

Nevertheless, starting around the turn of the Millennium, it was apparent to many thoughtful people that the pattern of the 20th century just couldn’t go on as it had and that something needed to radically change. There needed to be a modification to Western culture, not a modification in the liberating individualistic direction of the previous hundred years, but a modification in a more religious and folkish direction. The West had reached a natural limit; it could not continue to progress in the way it had without being inauthentic, and a new way needed to be forged.

But that new way was not forged, and so, instead, everyone returned to their usual patterns. Millennials discovered New Atheism, intersectionality, and Barack Obama. We did our best to make our spiritual identity secular and political, all the while LARPing as civil rights activists from six decades earlier.

Perhaps this choice to embrace a counterfeit version of 20th-century progressivism was an act of self-infantilization. But it was a choice made because all the other alternative paths to maturity and authenticity seemed impossible.

Modernity was a machine that only moved in one direction. The second it went against the grain, the system would break and backfire on the people driving it. To try to think of a new way or a new life that was different from the pattern of the 20th century, we needed a broader spiritual understanding of the universe that our generation just didn’t have. We needed an expanded knowledge of poetry and religion that would require deep searching to obtain.

Rediscovering such a spiritual imagination is essential for the future of human civilization. However, this project is much deeper and much slower than an entire society can accomplish over an entire century. It cannot be confused with the more ordinary project of growing up and putting away childish things, as challenging as we Millennials might find that more basic task.

This is a major theme of my writing, that our civilization is disconnected from its roots and can only make increasingly faded copies of things that once had real spiritual and emotional resonance. My project as an educator is to encourage a return to the well, with the Bible and myth as the foundation of a new renaissance. It’s what happened before and it can happen again.

As a 20 year old zoomer all the books I read are at least 10+ years old, all the video games I play are at least 15+ years old, I don't think I've even seen a movie made in the past 5 years, and I could not care less about contemporary music. While I am admittedly not the best representative for the typical zoomer It still is the case that young people like me are not that interested in art coming out today. Every zoomers favorite x is not of their generation.