How Do you fix a Problem like Magic (the Gathering)?

A quick response to Charlemagne on the woes of MTG

I am behind on my more serious writing. Nevertheless, I couldn't help but respond to this excellent piece by Charlemagne from the OGC blog on how elite theory explains the misgovernance of the collectible card game Magic: the Gathering.

People have been telling me that I should post my long substack notes as essays to generate more regular content, so I am experimenting with just jotting down some random thoughts and publishing them on the main feed to see what happens.

As long-time readers probably know, board gaming is my main vice, particularly those "deep" board games that have extended "meta" environments where part of the game is either deck-building or army construction that players manage outside of the game itself. In such meta-environments, the resources available for any game change over time to create an evolving play experience for people who participate in the game over a long period. To me, games with extended “metas” are fascinating because they force people to think about playing on two different levels, mimicking the "tactical level" thinking versus "strategic level" thinking that goes on in real-world conflicts. The existence of an extended "meta" also allows players to excel at either part of the competition and to"talk shop" about the game with other players, which, to be honest, is a large part of the fun.

However, the problem with these meta-style games is that they inevitably become corrupted by the people who manage them. On the surface, there is an easy explanation for why this happens. The fact that there is a "meta" means that the game is the perfect target for the “consoomer” lifestyle where nerds invest their identity in the products they buy. This situation, in turn, allows the corporations who own the IP to milk the fans for all they are worth. The process inevitably ruins the balance of the game, making it more of an outcropping of nerd identity and “consoomer” culture. You can see this pretty readily with what has happened to Warhammer 40k from Games Workshop (GW), or Magic: the Gathering from Wizards of the Coast (WOTC), as described in Charlemagne's article. What once was MTG’s most popular and fun fan-made format, “Commander”, was recently ruined by WOTCs desire to print and sell more cards to an ever-growing fanbase.

After a company like WOTC kills its own product, a perennial question about meta-gaming always returns; why don't fans fix the problem? Why can't they just take their toys and go home? Why can't they change the rules to make the game less financially onerous? Why can't they print their own cards? Why can't they 3D-print their own miniatures? Why can't they just "fork" the game in the state where it was actually good and then continue on from there? Aren't they a community?

Well, the answer is quite simple, as Charlemagne points out.

The MTG and Warhammer “communities” can't do these things because the fans of these deep games are NOT actually a community. They are just consumers. They have no organization nor ability to rule themselves. As such, they inevitably their bleed power back to the corporation that wants to transform their beloved pastime into another consumer product.

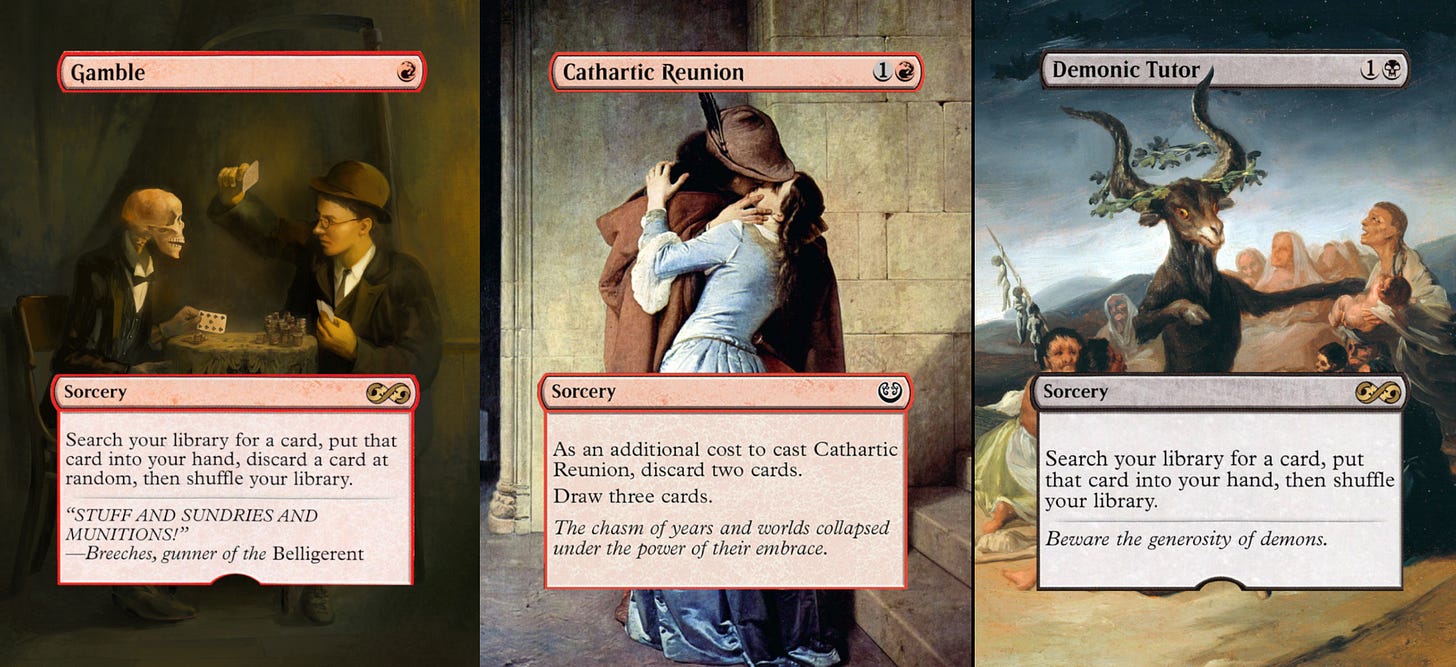

Case in point, I will take this opportunity to talk about an MTG commander deck that I made entirely out of proxies that I designed myself. As I am want to do, each of the cards used classic art that still reflected each of its original themes, creating a deck that was more visually unified and more thematically interesting than the boring fantasy art used by WOTC.

So what was the reaction to my 100 percent proxy deck?

Strangely enough, a surprising number of people didn’t like it. Even though proxies were allowed, a lot of players felt like making an entirely proxy deck was “cheating” the MTG meta. I was not participating in the same system they were, because I didn’t actually buy the cards.

It’s things like this that made me realize that a large part of the appeal of these meta games is the financial abuse itself. Like some battered wives, many MTG fans enjoy the fact that WOTC grapes their wallets, because their willing submission to the abuse shows that they really love the game. In the classic toxic archetype of "sadist meets masochist", the nerd “consoomer” of MTG wants to be a whore for WOTC because the abuse is what makes them feel like they are part of a "community", even though that feeling is an illusion based on a consumer product.

Still, might there be other ways around the problem of meta-board gaming?

For a while, I thought that the core issue was perverse financial incentives and that the solution to this mentality was simply to treat the meta-games like board games, print everything in abundance, give all players access to everything (for a small subscription fee) and then let people self-sort between “consoomers” and people who are actually interested in playing a game.

Enter one of my favorite games of all time: Android Netrunner, a “living card game” that followed just this de-financialized approach to deep board gaming. It was a better game than MTG, being MTG-creator Richard Garfield's second attempt to design a product that fixed the problems of his original smash success. And surprisingly, it sold very well. Still, the incentives of power consolidation eventually came for Netrunner in 2018.

The problem with Netrunner was that it didn’t have any power player in its corner. It sold well, people liked it. But the game never was a cash cow for the company that produced it or the FLGs that hosted it. So when WOTC pulled the plug on the project (probably to avoid competition with its other products) no one anted up to save Netrunner. Maybe it was inevitable. Power always consolidates.

Or does it? Because Android Netrunner actually survived being discontinued by the company that owned it. For once, the game “community” actually came through and acted like a real community, they took ownership of the game, designed their own cards, and governed a new independent game meta.

But this transition also marked my declining interest in playing Netrunner. Why is that?

You see, while Netrunner’s community might have saved the game from WOTC, they could not save Netrunner from the consequences of elite theory.

In order to be a community, Netrunner fans needed an organizing principle beyond finances, and inevitably they reverted back to progressive social justice and the game became insufferably woke.

It’s not that I had a problem playing as a computer hacker character who also was a disabled trans-furry. I could overlook aesthetics for a good game, and (for once) weird, progressive identity politics weren’t actually at odds with the setting, in fact, they made the cyberpunk world seem more dystopian. Nevertheless, what really killed it for me was the identity of the fans, who now saw being progressive as a core part of the game. Ironically enough, the necessary gate-keeping was being done, but I was on the outside of that gate and the game didn’t seem “for me” anymore.

Under these circumstances, I found myself turning to smaller deep board games, mostly products like MTG: Pauper and GW’s Blood Bowl or Mordheim, games widely played and still owned by the big companies but with small enough player bases not to be ruined by their own fans and the corporations who owned them. It works well enough to get some time once a month or so to “escape it all”, but it’s not ideal since I know that the moment one of these games gets super popular (as with Warhammer 40k or MTG: Commander) it will inevitably be ruined.

Such is the nature of life.

However, I suppose that the example of Netrunner does provide hope for fixing these meta-games inside a pre-existing ideological community. This is something that I think my fellow right-wingers need to consider as our organization efforts ramp up. It would be nice to have spaces where we just had fun.

Of course, board gaming is something of a meaningless pastime, which I often describe as a “vice”. But I do think these pastimes play a valuable role for men, especially young men, who need access to competitive environments that allow them to win, lose, and feel a certain amount of camaraderie that they might otherwise miss from not playing sports at a competitive level.

And isn’t there a certain educational aspect to these “deep board games”? They teach you tactical-level thinking when you play them, strategic-level thinking when you are preparing to play them, and political-level thinking when they are inevitably ruined by the people who own them.

Games teach people valuable lessons. And, in some sense, I am still learning.

We had a playgroup that used all proxies because real cards are prohibitively expensive. We encouraged creativity and as a marker we printed out a proxy deck of the top deck at the time: Tendrils of Agony, a deck that could infamously win on turn 0 or turn 1. We told everyone, "If you just want to win, here you go. Play out a hand, see if you can combo out to kill 4 players or so with 80 damage, then pat yourself on the back and the rest of us will continue the game without you but you can declare yourself the winner".

We had a tiny robust evolving meta as players one-upped each other with ridiculous board states and obscure situations and decks that surgically cut out the knees from other decks which had to diversify to compensate. It was great fun though in the end we settled for doing roleplaying over mtg - it gave all the fun and only the gm had to put in great labor over it.

At least the problem statement has been cleared up a bit:

- You need Elites to organize your hobby lest it dies or never even comes to be.

- You need those same Elites to resist the siren call of meta-gaming the meta to the detriment of a higher calling/meta. (Thus creating a consoomer class)

- You need those Elites to be your Elites.

I think that perhaps if you could design the hobby from the ground up with that in mind, wherein you teach your players those facts via the game mechanics, maybe it could just work?