In Christopher Nolan’s 2000 film Memento, a beleaguered investigator, Leonard Shelby, attempts to avenge the murder of his wife. As an added twist, Leonard suffers from a debilitating brain injury that makes it impossible for him to recall things that happened more than a few minutes in the past, forcing him to approach each new situation with no mental context and track his progress using notes, photographs, and even tattoos. Leonard's final permanent memory remains the death of his wife, a fact that keeps his motivation burning strong even while he is oblivious to the events he just experienced.

The protagonist’s condition alone would seem to make his mission impossible. However, when his partner, Teddy, questions whether a man with no functional memory is capable of pursuing a competent killer, Leonard repeats a notable piece of dialogue.

“Memory's not perfect. It's not even that good. Ask the police, eyewitness testimony is unreliable. The cops don't catch a killer by sitting around remembering stuff. They collect facts, make notes, draw conclusions. Facts, not memories.”

So, in other words, “Facts don’t care about your feelings”.

The sentiment sounds reasonable. But moments later Leonard assembles the facts and determines the guilt of his partner, who he executes without a second thought, coldly confident in his memoryless evidence-based decision-making. It’s brutal, but perhaps justified.

Perhaps not.

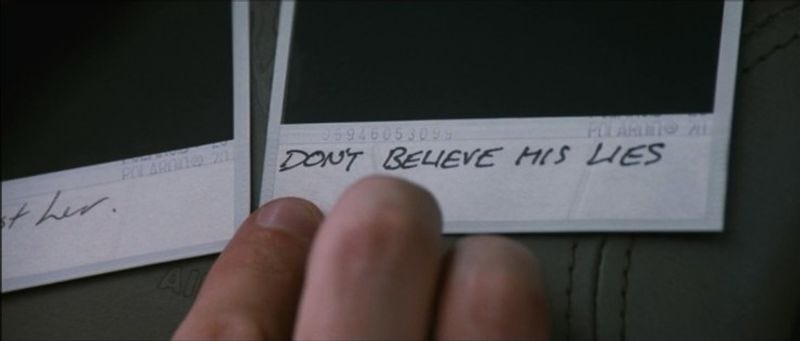

Nolan proceeds to show his audience, in reverse, the thoroughly circumstantial nature of Leonard’s “facts”, which all trace back to a single photograph of Teddy planted into his collection with a caption reading “Don’t believe his lies”.

Is “Don’t believe his lies” a fact? Not by any standard definition of the word. The phrase is just a moral opinion. Moreover, the photograph of Teddy containing the caption doesn’t even appear in the “evidence” Leonard uses to “prove” his guilt.

But it doesn’t need to. The captioned photograph is more powerful than evidence, it is Leonard’s context. It is the filter that draws his attention to every stray piece of evidence that demonstrates Teddy’s culpability and turns his eyes away from those facts that would exonerate the man, including Teddy’s quite reasonable arguments in his defense. But what are reasonable arguments coming from a guy who you suspect murdered your wife and who you know is trying to deceive you?

I am sure Nolan intended his plot twist to make some more general point about the fundamental subjectivity of human psychology. However, I always think back to Memento in the context of politics, especially when I hear about the importance of things like debate, evidence, facts, and statistics in determining the direction of a society.

For a while now, it has been clear that modern people need a better way of talking about ideas and their transmission, why some notions become normalized while others are consigned to taboo. Not that I have any novel theory, but the Enlightenment’s concept of ideas winning out through the force of reason, so popular in late modernity, is insane. The pretense continuously drives our society to failure points, prevents our leaders from internalizing necessary hard truths, and encourages elite condescension over perceived inferiors who they should be learning from.

Humans are not, as Leonard Shelby imagines, dispassionate arbiters of evidence and probability. Instead, human judgment exists inside a necessary narrative context that determines how facts are perceived and their place in a larger worldview which, in turn, determines what is fallacious and what is trustworthy.

Most people intuitively understand that narrative and moral perspective are essential to human thought. But this reality doesn’t integrate well with the modern paradigm that conceptualizes all decision-making as the simple combination of data and processing power. So, inevitably, our rulers are encouraged to categorize ordinary human behavior as the product of bad education and the values of the lower classes as a product of ignorance and bigotry, easily dismissed and held in contempt as the purview of slack-jawed yokels and paranoid conspiracy theorists.

It’s a ridiculous thought process to be sure. But it works well enough, at least enough to create an ideological lockstep managerial class impervious to questioning its prior assumptions.

As someone who was once part of this insulated class, people ask me how I “took the Red Pill”. Unfortunately, it’s not a very interesting story. However, what is an interesting story is how I ever “took the blue Pill” to begin with.

Despite being raised in a progressive community, I did not begin my young adult life (like so many of my cohort) as a leftist true believer. In fact, throughout my early intellectual development, I was very much dissatisfied with the center-left worldview pushed by my high school education, and not much more satisfied with the radical-left worldview provided as an alternative.

There just seemed to be something wrong about the moderate liberal perspective so foundational to where I was raised. And this feeling set me on a course throughout my late adolescence, reading heretical literature like Charles Murray and briefly experimenting with anti-progressive philosophies, all the while repeating the acceptable liberal opinions in public.

Not that I was “red-pilled” in any sense, my ideas weren’t even particularly nailed down. I just had a feeling of skepticism, a feeling that would peak during my first year at college, when one of my older friends began working on a made-for-TV documentary about the life of Amy Biehl.

Amy Biehl was a native of my own Northern California Bay Area, who in 1993 traveled to South Africa as an activist to promote racial reconciliation in the wake of Nelson Mandela’s ascension. However, Biehl’s activism was short-lived as she was subsequently ambushed by an anti-white mob and stoned to death by a group of angry Africans for the crime of being white. Her killers were soon after granted amnesty by South Africa’s newly devised Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

My friend’s documentary, like most other mainstream recountings of Biehl’s life, sought to portray the young woman as a martyr of a new racially reconciled nation. Despite her brutal murder, Amy Biehl was presented as a necessary sacrifice, and her killer’s amnesty as an essential symbol of the proper “turn the other cheek attitude” required to build a new post-racial society, free from sectarian strife.

Even as a college freshman, I found this messaging dissonant with the facts as I understood them. Biehl’s murder was just the kind of bigoted violence that was anathema to a successful post-racial society. Her killers, far from misguided revolutionaries, seemed transparently interested in cathartically murdering non-blacks, regardless of the political situation. And it wasn’t even clear how Amy Biehl’s murder, much less the extreme lenience shown to her killers, was going to stop interracial violence or crime generally, in South Africa.

And slowly it occurred to me that the story of Mandela creating a bold post-racial society from the shadow of Apartheid might not be entirely true.

A few hours on the pre-social-media internet were enough to confirm my suspicions, and it was not long before I found my way to a forum containing many South African whites lamenting the declines that their society had experienced since 1994. The facts, now de rigueur for most modern dissidents, were nothing less than scandalous in 2004: stories of rank corruption, sky-high crime, indiscriminate murder, racial targeting of Boer farmers, and an out-of-control racial preference system targeted at dispossessing the ethnic group that had built the country.

Mandela’s dream, in most of its ordinary experience, seemed nothing less than nightmarish. It was far from an ideological shift, but I was seeing facts that didn’t fit with the liberal progressive story about humanity’s future. South Africa was only one example, but I was pulling a thread that might unravel my entire liberal worldview if taken to its ultimate conclusion.

But I would not pull the thread very far.

Less than a year later, traveling abroad, I found myself talking to some faculty members at a local University, one of whom was a white South African woman. Eager to test my inconvenient facts with a native from the dark continent, I nonchalantly advanced some concerns that post-Apartheid South Africa might not be the post-racial utopia it was cracked up to be.

Unsurprisingly, my rather innocuous questions were immediately perceived as political and illegitimate. But rather than contest the facts about her country, my friend simply re-framed the matter, scoffing at what seemed to be a very serious political crisis in her home country.

“Of course, there has been a problem with crime and corruption.” She admitted. “But these issues are all being addressed by the government. The people who are constantly complaining and making this a political issue are just bitter old men, still upset that they lost in 1994. You know, like the Archie Bunker types in the United States.”

Archie Bunker? Yikes. I certainly didn’t want to be like him.

Maybe these stories about the decline of South Africa were just sensationalist Johannesburg crime-blotter headlines, exaggerated for an international audience and blown out of proportion by a bunch of bitter white men still unhappy that modern South Africa had left them behind. That seemed to be the unanimous perspective of the South Africans with jobs at elite universities, regardless of whether they could address my core factual concerns.

After all, what was the alternative? Siding with the Archie Bunkers of the world, and sharing in their loser worldview?

That didn’t sound like a good option to me. So if the facts happened to point in the Archie-Bunker direction, well, so much worse for the facts. It was better to just turn away from this issue and use my time to contribute to more important concerns better suited to someone with higher prospects.

The thought process sounds stupid in hindsight. And it was stupid to be sure. But there was a deeply human logic to my decision to ignore the inconvenient facts and look once more to the approved progressive line.

I wasn’t a naturally credulous person. I didn’t even want to join the popular progressive clique where I lived. But something inside my young subconscious mind understood the imperative of obtaining status and the greater imperative of avoiding its opposite. I wanted to be a person of quality, a thinker who approached the world in a way both proportional and reasonable. And to be a reasonable person of quality, I knew that I needed to not be like Archie Bunker, even if I wasn’t a progressive.

Well, at least I wasn’t a progressive at first. But I had chosen a path, despite myself, that would inevitably make me an orthodox left-winger through much the same process that had turned me away from the worldview of Archie Bunker.

Through all the prestige media I consumed, from the Daily Show to Steven Colbert to the blogs I read in the Atlantic Monthly, a consistent vision of what counted as good and trustworthy was being given to me. As a naturally disagreeable person, I readily critiqued the political perspective of the content I consumed. I even contested a large number of their facts. Still, I accepted their frame, their attitude, and, most importantly, their aspirational narrative of the enlightened cosmopolitan struggling against, and defeating, the evil reactionary troglodyte, the negative image of the Archie Bunker types. And it was that negative vision, especially, that steered me slowly and consistently to the progressive conclusion on almost every issue.

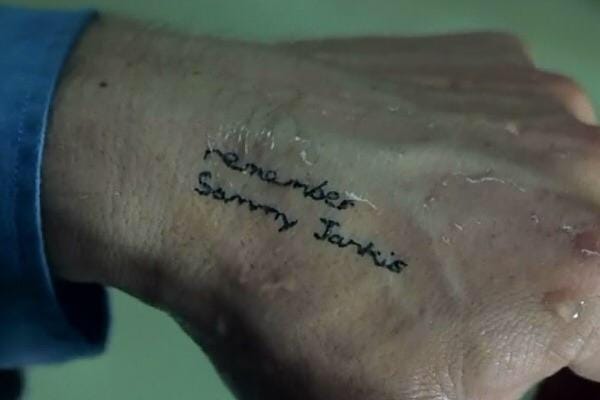

The cultural references weren’t always the same. But the vibes were. And they worked persistently in my subconscious, correcting my stray thoughts, and re-directing my speculation, always in the approved direction. Like Leonard Shelby seeing his tattoos in the mirror every day reminding him of his mission, I could almost hear the voice behind my eyes repeating the line.

“Remember Archie Bunker. Remember Archie Bunker”

But who was Archie Bunker?

Archie Bunker was a character from the 1970s television show All in the Family, intended by the show’s progressive producers to lampoon the conservatives who were dissatisfied with the negative societal transformations brought about by the 1960’s cultural revolution. I think I might have seen at most three episodes of the show, and, like most people who watched it, I found the character of Archie to be quite endearing. I also knew, from the outset, that Archie’s role in the show was calculated political propaganda, something that liberal California Boomers used to talk about like it was some kind of achievement.

And did it matter that, from the hindsight of 1999, Archie was in fact right about many of the consequences of progressive social change?

Not really.

Because until 2011 at least, Archie Bunker was living rent-free in my imagination as a cautionary tale, driving me to vote for policies I knew wouldn't work and publicly affirm idiotic ideas that I knew weren’t true. My memory of Archie Bunker was a one-way ticket to being a Reddit shit-lib, even before Reddit existed. And I couldn’t explain the reason why.

Ultimately, the reason was that I was thinking like a human being. I put my aesthetic moral ideals first and applied rationalization afterward. All humans operate like this. And despite our pretensions to be rational animals, reason is usually an afterthought. This is not to say that humans lack any logical agency, but it is a secondary motion, and mostly controlled by our aesthetic choices about the kind of people we want to be and the kind of world we want to inhabit.

At this point, I am sure my readers are expecting hand-wringing about “human irrationality”, cautionary stories about “Elephants and riders”, and exhortations to be more reasonable despite our base instincts. But as my understanding of mankind and history has developed, I am not even sure that the human mind is wrong to work in the way that it does. There is no thought without moral judgment and a preexisting understanding of ‘oughtness”. Therefore aesthetic preferences are essential to the quality of real thought and provide it with that dimension of wisdom which separates it from base computation.

The conceptual separation of factual reason from moral judgment is yet another core mistake of the late Enlightenment. Just as freedom must answer the question “freedom for what?” in order to become liberty; facts must demonstrate that they are operating in the service of some greater aspiration in order to become human truths.

Truth can never be divorced from a teleological understanding of reality, an understanding that humans ultimately obtain from pre-rational sources like experience, history, and (most of all) stories organized around the struggle between good and evil, the symbolic war between angels and demons. It is through these moral narratives that we cultivate the basic beliefs that direct the process of our self-development. And it was just this role that the negative vision of Archie Bunker was playing in my subconscious mind, despite my better judgment.

And, truth be told, my subconscious mind wasn’t ultimately wrong about those reactionary hate-facts. Pulling the thread out of the progressive political narrative would have ultimately led me to the opinions of Archie Bunker. And Archie Bunker was indeed a loser.

However, behind this reality was a deeper question that I was not prepared to ask; namely, whether there was anything about the old world’s moral vision that was more beautiful and true than the modern worldview which had replaced it. The question was inconceivable to my younger self, not because it was too rational, but because it was too large. The inevitable answer involved a radical break from what had come before and I lacked the historical understanding to grasp what might lie outside the world I knew. I needed some new set of spiritual symbols for a true moral transformation to be possible, the basis for all human ideological change.

Such an understanding of human ideological change might benefit society in 2024 where most public political discourse has become mired in a profound spiritual malaise. Whether left or right, there is a near-universal feeling of desperation and a sense that nothing can change and that all political action is futile. With decline accelerating and discourse collapsing we understand that political action is required, but also have a sense that most effort taken in that direction will be counterproductive.

Naturally, the various sides of the political spectrum experience the problem differently. The left is finally beginning to understand, not just the impossibility of many of their goals, but the profound fakeness of their entire political project, the pretense of phony compassion covering up the reality of avaricious political self-interest. The right, on the other hand, is only now starting to understand how powerless it actually is, rendering its fascination with political realism a tantalizing riddle and casting its aspirations to build a new order as a LARPY pipe-dream.

And, speaking for many other right-wingers online, the current situation is particularly pointed. Society is now transparently declining, the mainstay of the professional-managerial class is intent on pouring gasoline on the fire, while the security apparatus of the West considers us its number-one enemy.

But despite it all, there are few satisfying outlets available to us. Total victory is not in sight. And so our options are either to subtly plant the seeds of change on a larger scale, or try to slowly build in parallel. Neither of these projects’ accomplishments are immediately apparent, nor do they offer the possibility to stop the disasters looming on our horizon.

The situation is not very satisfying, especially for those of us with children or otherwise invested in living real lives, outside theoretical politics. But given that the mood of political desperation is afflicting virtually everyone these days, couldn't there be some solution found in compromise where each side takes what they need to move forward, leaving their vanity at the door?

In theory yes. But the reality of these compromises rarely plays out very well, always falling into predictable modes of failure and feeding into the problems it was designed to fix.

One such compromise has become popular with many post-progressive thinkers, especially those more adjacent to mainstream culture, such as Anatoly Karlin, Richard Hanania, or James Lindsay. These moderate perspectives imagine a return to normalcy that might be procured by seeking concessions on several key policy issues and un-PC facts (usually crime and various racial politics), while, in exchange, accepting recent progressive “social advances” and offering denouncements of “far-right” extremists along with anyone else who might hold unpopular socially conservative opinions.

Many dissidents mock these compromises as “return to the 1990s”-style thinking. And indeed, there is a great deal of nostalgia in these plans since they rely on America operating as it did in the late 20th century even when the nation has a radically different demographic character. Still, the proposition is attractive on paper, and, like most good political compromises, everyone gets something they need.

Progressives get an off-ramp from their own insanity, an excuse to reign in their crazy activists, and a chance to reclaim the mantle of being a policy-focused “reality-based” community. Furthermore, any reintegration of non-liberal parties into the mainstream power structure provides a pressure release valve for the leftist narrative as it allows good progressives to blame the consequences of their bad ideas on those heartless conservatives who didn’t let the egalitarian project go far enough.

On the other side of the equation, conservatives (and their new post-left allies) get a seat at the adult table, an opportunity to show everyone that their exposés on “liberal hypocrisy” actually matter, and a quantum of hope for their audience of middle-class families who don’t relish raising their children in an insane progressive dystopia. Additionally, the ascension of a moderate ruling coalition provides an opportunity for some (more culturally aligned) thought leaders as the ruling class is forced to admit, briefly, that they were correct on issues like crime and uncontrolled illegal immigration. The concessions seldom last, but this hardly matters to these heterodox thinkers as such acknowledgments are critical to their brand as true intellectuals and “Elite Human Capital”.

So, provided that a compromise based on exchanging policy moderation for cultural concessions is possible, what could be wrong with it?

The right-leaning parties get change on the ground, now, while the left’s victories are entirely abstract. Everyone wins, everyone except those socially conservative types like Archie Bunker. It’s the perfect compromise!

Well, it’s the perfect compromise if one wants to maintain the status quo. But it is the worst move imaginable if one wants society to learn from its mistakes rather than to repeat them. The exchange belies the fundamental modern misunderstanding of politics as an exchange of policy ideas rather than what it really is, a war of belief.

Many on the right talk a lot about the infamous “Neo-Con Cycle”, the process through which newfangled moderate forces in a right-wing coalition gradually take control of the movement and transform it into a carbon copy of yesteryear’s left-wing coalition. This is a pattern that has repeated throughout the last two centuries and has rendered the prospect of conservative politics almost entirely futile. What is the point of actually being right-wing if the most you ever aspire to be is the progressive party of two decades ago?

Nevertheless, few people understand how the “Neo-Con Cycle” works. In reality, it doesn’t really have anything to do with the specifics of neo-conservative ideology, its Trotskyist origins, its war-mongering, or its fascination with the free market. Instead, the “Neo-con cycle” has everything to do with cultural symbolism and how it drives politics inside the human mind.

Policy is transient. It exists only on paper. Facts, qua facts, are meaningless numbers, flashes on the screen forgotten as quickly as they are noticed. The only thing that persists and carries on throughout the generations is a belief in a story, a story expressed through culture and embodied in moral examples and all of those horrible spiritual things that don’t readily show up on spreadsheets.

This was the mistake of the original conservative movement. All throughout the 80s and 90s they won concession after concession both on issues and policy. Yet none of their victories were permanent, nobody ever seemed to learn anything. People thought the world had learned its lessons about socialism in the late 80s, political correctness in the early 90s, and crime and policing in the early 2000s. But these lessons never stuck in the public imagination. There was no place for them to stick, because all of the cultural symbolism produced during this period was pushing in the opposite direction, encouraging people in their progressive worldview even as its failures were dancing in front of their eyes.

Thus New Yorkers who lived through the”bad old days” before the late 90s could never remember the lesson of “broken windows policing”, even though they experienced its consequences every day of their lives. But they all remembered that gay men were charming yuppy professionals (even if they had never met one like that) because they saw it on Will and Grace.

Thus, even now, my former neighbors in Seattle can’t bring themselves to recollect that their neighborhood was taken over by insane leftists who shut down emergency services, robbed them, and murdered people on the street. Yet they howl with rage at the memory of a man in a buffalo costume taking an unscheduled tour through the capital building, thousands of miles away. They knew what they saw on television. They remembered the ever-present threat of right-wing extremism. They remembered Archie Bunker.

Here I will remind my reader that I am not talking about stupid or credulous people. This isn’t just how low-IQ plebeians behave. This is how all of us behave, those high-agentic “Elite Human Capital” types very much withstanding. We are all Leonard Shelby, the moral narrative we obtain from our culture is tattooed indelibly on our psyches, guiding our thought in every moment, the facts are trivia scribbled on scraps of paper, forgotten the second we aren’t directly looking at them.

My point here is not to take another dig at those “New Secular Right” types who dream of a socially-liberal return to sanity. Neither is it to denigrate all attempts at compromise, which I still believe will be an essential component of any political solution in the future. Rather, I am hoping we might think differently about ideology and politics, understanding what ultimately matters and what ultimately doesn’t, even if it requires some humility about how our own thought process works.

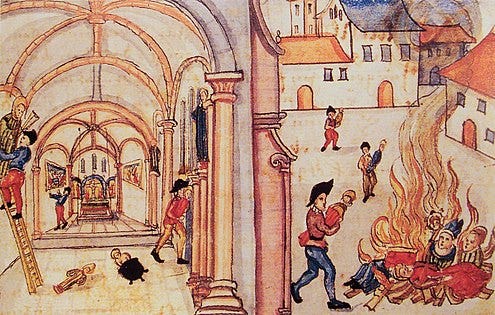

If long-term change is essential, which I believe it is, then it must begin with a change in the stories that we tell about ourselves, which means, in turn, discrediting the story of the 20th century starting with the idols and boogeymen that form its outline. We must fundamentally disrespect the symbols of the old order in order to break from it properly, otherwise, its gravitational pull will inevitably draw us back into the same tired orbit. A narrative sea-change is the only thing that actually lasts.

And such large-scale narrative shifts aren’t consigned to half-forgotten history books. In fact, one such shift seemed to be happening earlier this month when revisionist historian Darryl Cooper appeared on Tucker Carlson. As expected, Carlson and Cooper covered many topics, but the bomb didn’t drop until Cooper described Winston Churchill as the “real villain of World War 2” and the mainstay of online conservatives collectively lost their mind.

Superficially at least, it was very difficult to explain the unhinged reaction coming from ordinary normie-conservatives. Winston Churchill had always been a controversial figure. He was an undeniable war hawk for much of his career, and was famously responsible for the bloody fiasco at Gallipoli during the First World war. And that’s not to mention his questionable management of British colonial possessions. More to the point, as an undergrad, I distinctly remember a huge activist furor over Churchill’s possible role in killing millions in the great Bengali famine, with very little outrage heard from the college Republicans.

So why the outrage now? Why was every conservative pundit acting like attacks against Winston Churchill were the ultimate blasphemy, much worse, it would seem, than attacks against God Himself

The issue is not with Winston Churchill, the man. The issue is with Winston Churchill, the story. Conservatives need the story of Churchill to make their worldview make sense, more than they even need God. They need that image of that elder conservative statesman, the representative of the old world, who still stood up to fight the real right-wing bad-guys. They need that great representative of the British Empire who “took one for the team” and helped the forces of anti-imperialism conqueror the planet for the greater cause of “our democracy”. Churchill was the original beautiful loser, the original “good” conservative, the image that every patriotic center-rightist tries to emulate just as they also, paradoxically, try to avoid resembling the image of Archie Bunker.

And, if any conservative did entertain the notion that the “Great British Bulldog” might not be the century’s greatest hero, he would quickly find the narrative of the post-war consensus collapsing around him. Founding myths need to have heroes and villains. So if Churchill and Roosevelt weren’t the good guys then who was? Stalin? And if there weren’t any good guys, how could the great mustache-man himself, Adolf Hitler, be the bad guy?

Or maybe our concept of the entire 20th century is ridiculous. Maybe our notion of World War 2 as the “good war” is a mythologization of a great human tragedy, a war like any other with some heroism, more villainy, and no clear “good” or “bad” side. Maybe the Second World War wasn’t that different from the first, maybe it wasn’t the great crusade of legend where the forces of light defeated literal Satan and brought the world liberty, equality, and diversity.

Maybe we still live in history.

I, for one, think that living in history would do modern people some good. Even if it doesn’t align us with some deeper truth, it might dial back that 20th-century liberal hubris responsible for so many modern problems. At least it would make our elites less irritating. Maybe it would even solve the problem of stuck culture.

But such a reversion is a tall order, and it will take more than a few revisionist podcasts to accomplish the change. And modern people are distinctly lacking the ability to imagine anything different than the world which they have always known.

Ironically, to break from the narrative cage of the 20th century, modern people would need to have some alternative spiritual structures to show them the way. And in the early 21st century this spiritual sub-structures simply does not exist. All of our narrative touchstones are entirely captured by the post-war propaganda machine, from Indiana Jones (World War 2 in history), to Star Wars (World War 2 in space), to Marvel Movies (World War 2 in spandex). We have replaced our folk memory with the mono-myth of the 20th century, and each repeats the same stifling ideological message ad infinitum.

This is one of the true paradoxes of modernity, that in order to radically change their own politics, a people needs to studiously conserve their historical folkways. They need a set of symbols and stories that are larger and deeper than the narrative produced by the present ruling class, and a lens through which they can judge its flaws. Those spiritual traditions, the very things that the modern world claims to liberate us from, are the necessary thing to escape its grasp. And people with no understanding of their past will have no control over their future.

The situation creates a kind of “chicken-and-egg” problem. Insofar as the lack of living folkways prevents the dismantling of modern state propaganda, the existence of modern state propaganda makes the development of new folkways nearly impossible. Nevertheless, I see a necessary first step in actively accelerating the collapse of the progressive narratives that under-gird contemporary nations. They are declining anyway in the acid bath of modern skepticism, but there is a chance that this decline will provide a critical absence that human nature, abhorring a vacuum, will inevitably have to fill.

Thus, one of the main roles a dissident must play in the modern world is that of the iconoclast, clearing away the false gods of the progressive vision so that new life might have space to grow, a necessary beginning to the rediscovery of sincere spirituality. After all, isn’t that why trolling liberal pieties with “meme magic” feels oddly more authentic than trying to recreate new media properties that recapture the spirit of the 1990s?

Here I will offer a note of sympathy for the conservative reader who immediately grows skeptical at such a proposal. Shouldn’t someone who is aware of history be more cautious when trying to dismantle the sacred symbols of older orders, even older orders which have become corrupt? Everyone thinks they understand the process of radical societal change, yet few do. And while it’s easy to imagine tearing down the modern liberal order to install a Charlemagne, one might just as easily install a Tamerlane. One should stick to the devil they know. It could always be worse.

But I am not so sure there could be anything worse than a false god, much less a false god everyone knows is false but still expects to be worshiped.

Certainly, being in part the product of humans, all belief systems have flaws. They all lapse into falsehoods. They all have corrupt priests. But at some point a faith goes from having corruption to being a corruption, from containing some falsehoods to being a false thing in itself. There is a line that a worldview can cross, a point of no return beyond which a faith can no longer be tolerated. And the religion of progressive modernity has crossed that line many times over.

There were warning signs everywhere, but for me, the damning moment for the modern ideology came when I discovered that its contemporary priest caste did not care about the truth of its ideas, just their utility in maintaining an order that benefited them. All true believers want genuine converts, fellow devotees who can share in the glory of the thing they love. But at some point in my lifetime liberals stopped looking to convince people of their ideals and just became interested in cornering the avenues of power. Yet they still force us doubters to voice the platitudes of a god that they don’t care about.

Such a vain perversion of faith is an unworthy object of worship for any free human with dignity. And the impious cult of progress deserves to be swiftly cast into the dustbin of history with whatever force and vigor our species still might muster.

But maybe I am being rash. Maybe I am letting my anger get the better of me. Perhaps the conservatives are right and the wiser course is always to seek refuge in the humility of compromise.

But, to be honest, I don’t know if I can. Not anymore.

I have noticed too much. I have seen the reality that persists behind those pretty lies about “equality and freedom”. I know what the ultimate price will be. So now, when I encounter any part of the progressive story, from its promises of eternal affluence, to its attempts to create human well-being via material comfort, to its pleas for stability by means of a false compromise, an epitaph appears behind it all. It is a simple message my mind has written indelibly on my subconscious. It reads:

“don’t believe their lies”

This is an _outstanding_ essay. I could restack every paragraph.

I agree that Archie has become a gremlin. However, I'm old enough to have watched the show as a child with my parents every week. I remember Archie before Norman Lear told everyone they were supposed to despise him. My dad at the time was a Democrat, but he loved Archie. Part of that is due to Meathead, who was presented as an enthusiastic idiot. The contrast gave Archie the aura of a cynical yet wiser man. And Edith, a saint, loved him, so he had to be okay.

How did that Archie become the icon of a conservative troll? I don't know. Your argument that our stories are more important than our policies seems strong. How are our stories built, though? There's an alternate future with an Archie story that's different, possibly. Or, every story is a result of truth. In that case, Archie could never be anything but a rightwing monster.

I think your argument has another layer to it. It's been thought-provoking. Thanks.