Lost Generations

A man without a people has no future

Sometimes, a provocative article is published, generating considerable controversy. Yet what is interesting is less its thesis and more the reasons for its success in its unique historical moment.

One such article was published last month in Compact magazine by the illustrirous Jacob Savage under the title “The Lost Generation,” detailing the extent of discrimination against white men since the emergence of hard DEI policies in 2014. Savage’s writing was unflinching; his journalism tight, and his claims well-supported by numerous citations and statistics. The man had done his homework and had his facts down cold. Moreover, Savage brought his facts to a point that cut deep into the modern managerial elite’s conception of itself and made quite an impression.

As Savage recounts, the problem for aspiring professional white men in the 21st century stemmed from a pincher movement between two trends that had developed over the last half-century. The first end of the pincher was the left’s growing institutional dominance, which, by the early 2000s, had resulted in a nearly uniform professional class ideologically obsessed with the specter of straight white male oppression. The second end of the pincher was the introduction of mass migration into the Western world, which radically expanded the non-white share of the nation’s population, exacerbating perceptions of minority “underrepresentation” and bolstering demands that policies be implemented to ensure that America’s leadership class reflected the nation’s new demographic reality.

Initially, when introduced in the early 1970s, such preferential policies (or “Affirmative Action”) were considered a minor corrective measure for a country that was almost 90 percent white. After all, it was just a matter of letting the non-white tenth participate in the prosperity that everyone else in the white middle class had attained easily. As proposed, “Affirmative Action” didn’t entail a substantial sacrifice for those in the mainstream, but rather a few setbacks that could be easily overcome through more old-fashioned hard work.

Fast forward to 2020, with a white population approaching 60 percent of the country, heading towards minority status, these preferential policies looked very different. Since the core institutions that dominated America had been created at a time when the country was overwhelmingly ethnically European, radical action was needed to reach racial parity. In fact, to properly represent the country’s new demographics, the preferences cutting against white-men had to be kicked into overdrive, and it wasn’t going to be the rich Boomers in senior leadership with their heads on the chopping block.

In fact, if you were a boomer in upper management, educated to be a good liberal, bringing ethnic diversity to your company was easy, even as the targeted quotas became increasingly steep. Seniority mattered, and they were never going to fire the experienced, older white men. Subsequently, the diversity targets were achieved primarily at the expense of young men, and the effects were evident across the population.

The diversity regime took its toll on young men’s opportunities everywhere. And the consequences were manifest: in college admissions and jobs never granted, in first promotions not offered, in gigs that were never available, and in submitted manuscripts that were left unread solely because the authors had the wrong skin color, gender identity, or ethnic background.

As it turned out, “Affirmative Action” was pure class and generational warfare. The older generations got all the benefits of majoritarian-white privilege in a white country on the way up, then took credit for abolishing their privilege, leaving young men with the bill, and scolding them when they complained about their ruined opportunities.

The word “Boomer” stings for a reason.

In his article, Jacob Savage laid out the logic that dispossessed an entire generation of Millennials and Zoomers, making it impossible to look away. His piece was brilliant, and a shoo-in for one of the most influential articles of 2025.

So then, why the questions over the article’s sudden popularity after its publication in December of 2025?

Well, mainly because most of Savage’s points were not remotely original.

In fact, the author’s case had been made many times before, and had seldom received such an animated response from the professional class. None of the arguments Jacob put forward were new, and many excellent writers had laid out similar indictments only a year or so earlier, often with much more pointed conclusions.

So why was everyone so interested in talking about the problem now?

In part, Savage’s success was a matter of luck and timing: his piece was released in 2025 at a low point in liberal self-confidence, and was received by an elite managerial class seeking permission to discuss the excesses of the woke era.

As such, Jacob Savage granted these elites the permission they sought in a package that avoided many pitfalls that had stifled previous whistleblowers. Prefacing his incontrovertible statistical case, Savage made a subtle cultural appeal through his personal story, offering an emotional narrative of frustration and undeserved exclusion in a way that many moderate liberals would understand. So many men’s lives had been sacrificed for the dream of diversity. And it wasn’t even clear what “diversity” had achieved for society broadly.

Here, Savage’s decision to publish in Compact magazine was almost too perfect, as, in 2025, the magazine had become a kind of midpoint between the elite and populous factions of the American political scene. When all important truths are outside the Overton window, but mainstream leaders want to appear relevant without sounding radical, ambiguous areas for discourse are needed. And Compact provided that combination of respectability and plausible deniability, allowing the professional classes to quietly own the consequences of their own mendacity. Savage had created the perfect policy permission piece concerning the reality of racial preferences.

However, as I read the article for the second time, Savage’s piece seemed to be implicitly advancing a different conversation, one that was less about policy and more about the failure of intergenerational dialogue. In the 21st century, a necessary conversation did not occur because power prevented it. Now, at last, the “worms” who had impeded productive discourse are being exposed; the rest of us find ourselves in the confusing aftermath, uncertain about what comes next.

Worms in “The Conversation”

Perhaps to find out what comes next, we need to dig deeper into how we got here.

For everything else people are saying about anti-white discrimination after 2014, men my age or older will remember that this process began much earlier. There were stringent “Affirmative Action” policies throughout the 90s and 2000s that kept many talented people out of key positions, and these preferential systems were continuously expanded in ways that would otherwise have been unsettling to middle-class Americans who believed they were working within an individualist “meritocracy”. To persuade skeptics to accept these new circumstances, a particular form of organic presentation of the new policies was required to demonstrate that these changes resulted from consensus, compromise, and “democracy.”

Behold the ascendancy of the American “Conversation about Race” as an ubiquitous feature of political life from the late 1980s to the late 2010s.

Sure, no one wants to believe that we are creating a top-down system to exclude and dispossess a non-insignificant part of the population. However, if that conclusion is presented as the endpoint of a debate or the result of something “we all agreed to pursue,” then the top-down approach to robbing people doesn’t feel as exclusionary or disempowering. You see, your leaders aren’t taking anything from you; they are just trying to have a “Conversation”.

In fact, despite the long-term, predictable harms of unnecessary discrimination against white men, many people stood to benefit from these new policies and were ready to push for their broader implementation. Therefore, “The Conversation” was naturally driven by people already supremely bitter about their place in society who considered themselves the deserving beneficiaries of unfulfilled social justice. For that group, there was probably no better use of time than to step away from the tasks at hand and have a “conversation” about unearned privilege and how to make things more fair.

Looking back, “The Conversation” was a masterful piece of cultural control, a wonder to behold, and the setup should be familiar to anyone who has ever undergone diversity training or attended a political science course.

In “The Conversation”, the group leader (almost always an over-credentialed, over-educated, dim-witted woman) introduces some DEI proposition, usually involving a combination of unfounded historical claims, bad anthropology, and restorative justice at the expense of straight white men. In their presentation, these ideas are all introduced as open questions, things we are “working through in conversation”, where people are free to disagree, and criticism is welcome.

However, in reality, the “Conversation” is a staged read-through with pre-determined conclusions and pre-set winners and losers. The organizer isn’t asking questions dialectically, but rhetorically. She raises issues while already holding preset answers, not to address objections logically, but to frame objectors as otherwise bad people. These passive ad hominem are terrible form for any real discourse, but the purpose of “The Conversation” is almost never to convince people, but rather to sort participants politically into various categories of “clients”, “allies”, and “critics”, then dole out privileges according to the level of cooperation exhibited.

Predictably, within “The Conversation”, it is ideal to be a “client”. If one belongs to a group that plausibly can be portrayed as an oppressed minority, one cannot be the proper subject of criticism. However, for those not plausibly part of any oppressed group, there is a necessary decision that needs to be made about how to react to “The Conversation”, and there are only three real options. First, one can take the bait and try to critically engage with the issues, becoming a foolish “dissenter”. Second, one can abstain from any overt reaction and present oneself as a “stoic” bystander. Or, lastly, one can assent to one's own humiliation and endorse the vilification of one's group, becoming a “worm”, dishonestly parroting slogans, accepting the guilt, and trying to derive personal benefit from the situation, regardless of the ridiculous ideas being proposed.

But in any case, there was no way to actually win. In “The Conversation”, men could be dissenters, stoics, or worms, but each role was bound to play out to their detriment just in different ways and on different time horizons. Though it was interesting to observe how each strategy played out.

For instance, for many white men, the natural response to being invited to “The Conversation” is to attempt an actual conversation. Why not let your objections be known, show the opposition up with “facts and logic”?. Naturally, if you liked debate, shouldn't it be easy to be an outspoken dissenter against the prevailing diversity orthodoxy?

In theory, this might work. But the manager running “The Conversation” at your college or workplace was in possession of a trump card that could render all objections moot, a card that simply read:

“Stop Whining”

The accusation of “whining” is a brilliant rhetorical strategy because the word is otherwise impossible to consistently define.

After all, in conversation, people are supposed to voice objections. But while objections are good, whining is always bad. The bright line between them is almost purely intuitive, and the two sexes have radically different intuitions about what characterizes the difference.

In masculine discourse spaces, “whining” is an objective description of a way of voicing grievances that is non-conducive to procuring solutions. There are guys who moan about problems but never fix them or implement the advice other men give them. They just complain to get sympathy, and for men, sympathy doesn’t solve problems. As such, “whining” is a futile activity; it weakens allies, drains group resources, and ties people up in endless drama.

However, the word “whining” has an altogether different definition in female spaces. In female spaces, concerns are not evaluated for their solution-orientedness. In fact, most female discourse is not solution-oriented. Instead, objections are considered legitimate or illegitimate to the extent that the person making those objections is considered legitimate or illegitimate. In the typical female pattern of preferring people over things, the status of the objections corresponds to the status of the person who typically voices them.

Does the girl talking about her problems have high status? Are her problems considered high-status problems? Could we share in that high status by commiserating with her?

If the answer is “yes,” then the problem is significant and warrants consideration by everyone. If the answer is “no,” then the problem is just “whining”. No one cares about your low-status problems, and you are a bad person for imposing this emotional labor on everyone else in the group.

This formula makes sense socially but is recursive and highly unstable. The group follows status, and status is determined by who follows the group. The elephant stands on the turtle, and the turtle stands on the elephant. The snake eats its own tail. And small changes in the emotional equilibrium can cause radical political cascades of opinion within female circles.

Subsequently, the only way such a dynamic achieves a modicum of stability is when a preexisting concept of status and morality is imposed from the outside; hence, the tendency of female-oriented groups to advocate granting more power to those already in charge.

The female understanding of what constitutes legitimate objections is a bad formula for independent thought. But it is the perfect formula for enforcing political orthodoxy. In fact, when it’s clear which answer is “right,” and the conversation can’t lead to any other conclusion, how could dissent be anything other than “whining”?

In the meantime, anyone who knows better can witness the futile opposition flail. The dissident gathers the facts, makes his case, and presents his argument, typically only to be dismissed out of hand, with further attempts to refocus the critique met with the classic passive-aggressive counter-accusation.

“Why are you whining?”

“Why is my argument whining?”

“I don’t know. You just sound desperate and insecure. It’s just weird to hear someone complain about all this when everyone normally sees it as common sense. Only weird losers complain about things like Diversity and Affirmative action. Voicing your disagreement is a bad look. It sounds like whining.”

Checkmate, Chud.

The case is airtight, and its ad-hom circularity doesn’t bother a mostly female audience trained to see circular, self-justifying validation as the way conversations are supposed to work.

The discourse longhouse is in full effect.

Moreover, these status-based attacks cut deeper when the leader responsible for “educating” the group controls the microcosmic measures of success, such as grades and certifications. Sure, your reasonable arguments against slavery reparations sound compelling when juxtaposed against Maya’s hysterical ramblings, but things look different when the term papers come back, and her essay gets a top mark, while yours barely passes.

I know you don’t like these scary new ideas, Johnny. But perhaps you should have put in the work, gotten a hold of your own fragility, and learned to write a little better. Perhaps you should spend more time listening and less time whining? You wouldn’t want this poor performance on your permanent record, would you?

Here once more, the low status of dissenters becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. The opposition relents, the madness of the female crowd prevails, and ideological non-compliance becomes unsustainable. The futility of the dissent game is plainly on display, and only fools keep playing it. I was stupid enough to try out the role of public dissenter against DEI as a freshman in college. I wasn’t stupid enough to try it twice.

But with dissent off the table, what other options remain for the straight white man in the middle of “The Conversation”?

Perhaps he might follow that ancient wisdom, “if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em”?

After all, compliance is an option. Adults all have to make peace with some amount of social conformity. So if there was a respectable way to comply with the other contradictions of the modern world, certainly there must be a respectable way for a white man to comply with DEI.

But as it turns out, there wasn’t.

As all Millennial white men eventually learned, it was impossible to be on the right side of cultural progressivism because cultural progressivism required white men to be on the wrong side of it. No matter what you surrendered, the ideology would ask for more. No matter what concessions were made, they were never enough. No matter what line you drew, the DEI revolution would cross it.

Whether you went full communist or, like me, tried to find a place on the technocratic center left, it eventually became clear that progressivism had no use for white men, at least no use for white men who weren’t constantly apologizing.

In fact, modern progressivism didn’t even want to make white men into true believers of its cause. That should have been the telltale sign that modern progressivism was fake to its core. Living religions desperately want believing converts, the more fanatical the better. Conversely, dead and effeminate ideologies just want compliance and fear. They are too dependent on existing status systems to sustain genuine fervor, and forgiving enemies tends to confuse their narrative. As such, modern progressives never feel comfortable when strong white men join their ranks.

But the situation for leftism in the 21st century was worse. The ideology of DEI-progressivism needed white men as villains because their ongoing humiliation was part of their product. It was what their clients wanted. As such, the progressive egregore insisted on performative self-disparagement until the self-respect of any white male present was burned away, and all that remained was a groveling worm.

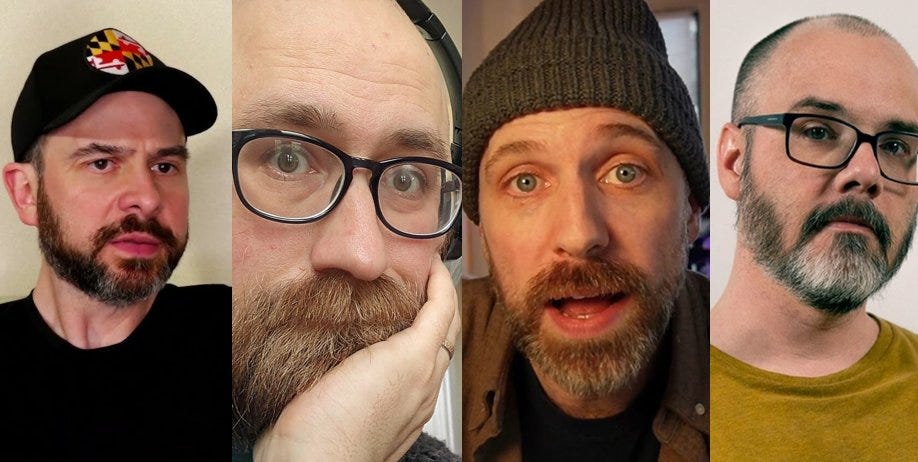

We older Millennials all recognize the men who followed this course to its conclusion. They all held themselves in the same defensive manner. They all spoke in the same way, like catty teenage girls. They even looked the same: balding, bespectacled, bent, and castrated. Such an image might be hard to summon for a reader who didn’t frequent progressive spaces in the 2010s, but, as fate would have it, the internet has furnished us with countless immortalized examples of this archetype in the white male luminaries of BreadTube, from Ian Danskin to Dan Olsen to Steve Shives and Michael Burns.

What more is there to say about these worms?

It’s certainly not hard to see why other men hate them. They are traitors. The worm begs for scraps and gibs to sustain their own sorry existences, which they have no right to hold under the logic of their own ideology. Progressives needed buy-in from some white men to advance their movement, and these were the men who were willing to comply for personal benefit.

At least I assumed they received some benefit from their self-debasement, but by the early 2010s, it was difficult to see what they gained from it. There wasn’t any professional payout for Millennials cooperating with the racial preference regime, the way there was for Boomers and some Gen-Xers. Women found them pathetic, despite their politics. Moreover, these progressive worms’ personal lives were almost always a chronicle of failure, weakness, and self-destruction.

Were these men always broken wrecks with no self-respect or backbone? Or had their ideology made them that way?

Neither would surprise me.

In fact, as far as I could tell, the only benefit that most of these worm-types seemed to get from their relationship with leftism was the opportunity to dunk on their non-progressive contemporaries, to finally be on the winning side of a conflict for once. Invariably, these leftist men had an obsession with seeing the chuds fail, piling on every anti-white recrimination and making sure that the nails that stood up got hammered down, dishing out the same disapproval against the “whiners” who otherwise deserved nothing and hadn’t worked hard enough to confront their privilege.

Oddly enough, in addressing the “whining” of straight males, progressive men echoed the typical Boomer bootstrap platitudes that they would have rejected in any other situation. Simply, mention any problem faced by whites or men, and soon, every worm in earshot would descend upon you, wielding catty slogans about how we all need to “put our big boy pants on, set our cheeks to the grindstone,” and make peace with our own proletarianization.

I imagine that the cognitive dissonance was part of the appeal. Inside “The Conversation,” the worms were playing a game where they always won, and all other men lost. It was an empowering dynamic. But the worm could find empowerment in no other places in the progressive world because, outside his essential rhetorical role in “The Conversation”, he existed as little more than a jester. No one respects traitors, much less weak traitors, and eventually the worms lost their allies' esteem and crashed out in their own ways. As anyone with any wisdom could see, the path of self-abasement held no future for the men who followed it.

But if white men were too smart to dissent and too wise to turn themselves into self-hating worms, what options remained inside “The Conversation”?

Eventually, almost everyone from my generation found their way to the only remaining answer: a stoic acceptance of the new DEI regime.

You couldn’t fight the ascendency of anti-white anti-male progressivism, and you couldn’t join it either. So all that remained was to grin and bear it, hoping for the best, silently trying to present a sense of apathetic invulnerability.

After all, we told ourselves, it would all come out in the wash: these policies were small, and eventually the quotas would be met, the systemic inequalities would be addressed, and America would return to its individualistic and meritocratic commitments. The probability that any of us would be directly disadvantaged by this ideology in the real world was small indeed.

We repeated this story to ourselves because we had to, even though we had no reason to believe it was anything other than a way to cope with our own ideological compromises.

Now, a decade or two later, the data is in, and it is apparent that the effect of these preferences was neither small nor temporary. Things did indeed go much, much too far, and we all paid the price for our cowardice. Moreover, what is worse, it was now impossible not to see that we had a hand in our own dispossession, just as much as the progressive worms we despised.

We thought we were being stoic, silent dissenters, standing above it all. However, we had to collaborate with the system spiritually, in how we understood our identities and in our failure to take collective responsibility for the fate of future generations. Our pusillanimity was evident everywhere, but perhaps no more obvious than in how we chose to discuss, or not discuss, the problems looming on the horizon.

Cover Your Ass, Mrs. Robertson

As everyone knows at this point, holding frame is the key to winning discourse, especially political discourse. You can win every rhetorical battle and lose the ideological war. It doesn’t matter how many times you defeat your opponents logically; if you concede their moral assumptions, you have already lost. The frame determines what counts as a valid question and the conversation’s ultimate goal. After that’s determined, almost nothing else matters.

After all, what is the point in talking about an issue? Are we trying to understand a system? Fix its problems? Or otherwise just smooth things over and decide who gets to take the blame?

Alternatively, in a technical context, I have noticed two broad types of analysis during my time as an engineer. The first type of analysis is intended to actually get at the truth and reveal what’s actually going on, a mode that I colloquially call “Getting To the Bottom of Things!” (GTBOT). The second type of analysis is a performative political practice designed to avoid blame, often referred to as “Cover Your Ass” (CYA). At a superficial level, CYA and GTBOT analyses operate in the same way. However, once you see the difference between GTBOT and CYA, you can’t stop noticing.

When an Engineer is trying to “Get to the Bottom of Things,” they are invested in the system's outcomes and take ownership of its ultimate results, POSIWID. They find problems to prevent disasters. They do what’s necessary to ensure the product has a high-quality outcome. They want to fix errors even if they are someone else’s fault.

By contrast, when doing CYA, you are performing analysis for almost entirely negative political reasons. To point things out so that people know that the product’s failures are not your fault, so that when the thing breaks, you can come back with the receipts in hand and tell all the bigwigs, “I told you so!” and get congratulated for being smart.

Perhaps my favorite example of CYA analysis is the oft-cited 2011 film Margin Call, which depicts 24 hours inside a New York Hedge fund after the leadership is made aware of a critical flaw in its risk model and decides to pursue a fire sale of its assets, which capsizes the market. Everyone naturally recalls the famous scene in which the junior analyst explains the dire situation to the CEO, and the ultimate decision to take drastic action is made. However, another interesting moment occurs later among the senior managers as they try to decide who will take the blame for the mistake that cost the firm trillions.

Naturally, people look to Sarah Robertson, the reptilian senior risk manager played by Demi Moore, who has spent the first half of the film terminating the careers of her junior analysts just before one of them discovered the error that spelled doom for the firm’s business model. When approached by senior leadership about her role in the disaster, Robertson offers her own meticulous preprepared CYA:

“Of course, you are well aware I filtered several warnings to you and Cohen over a year ago on this (problem)?”

Of course, you see, she didn’t make a mistake. She filtered warnings to people. But what are filtered warnings?

By “Filtered warnings”, Sarah Robertson means that she sent a handful of emails to her superiors alluding to the problem and framing it as “a possible concern for the future”. None of her warnings framed the issue in the stark way that would trigger an emergency board meeting and set off a drastic response. None of these e-mail messages “voicing concerns” would prompt the firm to abandon its business model. In fact, Robertson’s warnings would likely be accompanied by other messages that endorsed the status quo and presented a rosy picture of the firm’s financial stability. Sarah Robertson wanted to object, but not to rock the boat because the stability of the boat was beneficial to her career. The analysis she performed over the firm’s risk model wasn’t designed to get to the bottom of things; it was designed to be CYA, the “I told you so” documents that allow her to appear blameless when everything else went up in flames.

Really, it’s hard not to think back to Sarah Robertson’s CYA when I look back on the decades of moderate criticism and commentary on racial preferences and DEI, criticism that I consumed and even participated in, first as a moderate progressive and later as a moderate conservative.

Our understanding of the situation was always passive. We knew that the system had a problem with how it addressed fairness and diversity, but we only felt comfortable voicing those concerns if they were padded and measured and didn’t risk overturning the comfortable status quo. We knew there was a larger problem, but we didn’t want to really get to the bottom of it; we just wanted to call it out so it might be said later that we didn’t approve of the bad things that had been done.

Now, following Savage’s article, the mainstream can finally acknowledge the real damage of preferential policies, and the moderates emerge with their milquetoast CYA analysis of DEI, pretending as if they had been heroically fighting against this inequity the entire time.

Whether it was moderate progressive worms like Matt Yglesias and Noah Smith who spent their entire careers shilling for the political party that made DEI a core part of its agenda, or the moderate conservatives like Megan McArdle and Conor Friedersdorf who had offered caged criticism of preferences without ever digging deeper into its systematic implications, the story was the same. It was the story of the honest, reasonable objector, long suspecting DEI might have some negative consequences, only now discovering, to their horror, that decades upon decades of overt discrimination against white men actually caused substantial harm.

As Captain Renault might put it:

“I am shocked. Shocked that anti-white discrimination is going on in this country!”

Nevertheless, despite their phony routine, I got the sense that the moderate conservative crowd felt genuinely flabbergasted at the situation.

Why was nobody celebrating these reasonable conservatives for being brave critics of racial preferences all these years?

Why did nobody believe them when they said they never could have known things had gotten so bad?

Why was no one even giving them credit for all the polite warnings that they had filtered to the American public over the years?

For decades, they had been critics of Affirmative Action and racial preferences, but their criticism always began and ended in the same place. The writing was always extemporaneous and detached, highlighting the problem while, at the same time, almost explaining away its more troubling implications.

The point of any article by Megan McArdle or Conor Friedersdorf was not to expose the status quo’s more fundamental systematic problems but to model disagreement in an optically acceptable way. The issue was always complex and nuanced, requiring the subtlety of deep expertise. The problem was something to consider, but not a proper target of outrage or concerted political action.

The conclusion of the analysis for this set was consistently a reserved, critical, and bemused attitude towards the system, leaving a reader, like myself, to think wistfully: “There are serious issues with the way things are, and I am glad serious people are noticing so that the experts in charge make sure things don’t go too far.” But it was just this kind of comfortable CYA analysis that ensured things would go too far, that there would never be a meaningful response, all criticism would be theoretical, and the problem would continue to erode society. It wasn’t my job as a conservative to upset the status quo. In fact, wasn’t I benefiting from it?

Strangely enough, at the time, this kind of divested, moderate criticism felt “adult,” even heroic. But looking back, it’s hard not to see the practice as just a slightly more dignified way of being a DEI worm. The system used our own skepticism and reasonable dissent to give its policies of radical dispossession an aura of legitimacy.

But then, what were we supposed to do about the situation at the time?

In fact, what are any of us supposed to do about the situation now?

Because of all the hand-wringing and recriminations that occurred in December 2025, I can guarantee you what will not happen in 2026.

There is not going to be any spiritual self-examination by the elites driving these institutional trends, at least not beyond what was already undertaken in the week following the publication of Savage’s permission piece. No one in government (outside of a few far-right corners of the Trump administration) is reconsidering the Civil Rights paradigm writ large, much less pushing to restore the lost opportunities robbed from a generation of men.

Moreover, while it now seems fashionable to talk about the exclusion of straight white men from professional life during the “woke decade” in the past tense, this language is used only to obscure the fact that the racial spoils system responsible for the previous dispossession is still very much in place.

The guaranteed sinecures for women and POC still exist, and the implicit quota systems for academic and professional advancement are operating as usual. Moreover, though the wheels of this system may have slowed somewhat in the wake of the second Trump administration, no one in power is under any illusions that once the Democrats regain control, this same engine of exclusion will ramp up once more.

Also, among the things that certainly will not be happening, I wouldn’t count on some violent revolutionary uprising by young dispossessed white men occurring in the near future. Yes, such an uprising would be historically precedented. Yes, such an uprising might even be, in some sense, justified. But it is just not possible in modern circumstances. The demographic of young men is too small. The status quo is too entrenched. And everything about our contemporary society is designed to stop just such an uprising of middle-class people. The dispossessed generation lacks a self-concept or sense of collective organization. And those who pursue political power or retribution without organization are simply digging their own grave.

That’s not to say there is no hope. But hope must be found on the other side of a different conversation. If Jacob Savage’s article exposed a generational theft, then any solution would have to begin with a generational dialogue. But such an intergenerational conversation seems less possible than ever.

Artax, Zoomers, and our Generation

Personally, I feel a certain moral weight in my role as an older Millennial. If there is anyone who needs to do something with the problems of the Great Dispossession, it is my own cohort. The Boomers are too old, already retiring, and unable to understand or even care about the problems young people face. Generation X seems destined to be passed over, while those younger generations native to the online woke world seem to be too scarred by their experiences to help themselves.

We, older Millennials, remember the time before and are still somewhat bitter about unfulfilled promises. We are not yet certain how this situation became so bad, nor what to do next. And we are not innocent.

We benefited from those unsustainable false luxuries for a few years before the opportunities evaporated and the gates closed on our future. Subsequently, we spent a substantial portion of our youth coping with the situation, defending the system, and covering our wounded egos rather than trying to find an escape hatch from our misfortunes.

Certainly, something has to change. We owe the younger men who bore the brunt of the exclusion something more than a shrug and a half-hearted “I told you so,” like Sarah Robertson and her “filtered warnings”.

It has been almost 10 years since I discarded my faith in the liberal world order. Moreover, although many Zoomers have found their way to the same post-liberal perspectives out of necessity, I still find it almost impossible to communicate with them in that deeper way that I feel is necessary. There has been a semantic collapse, and our ability to transmit signals across generations through cultural tropes has been nearly destroyed.

For instance, in the wake of Jacob Savage's article (as well as numerous other permission pieces exposing the mainstream’s persistent mendacity), it is clear to most well-meaning people that there remains only one solution: building in parallel. Reform is not coming. The institutions that exist are already staffed by our enemies, who have no incentive to change. There is no groundwork for a populist revolution. Moreover, the possibility of top-down regime change remains entirely beyond our control. The only way out is through; accordingly, the only solution is to build what we need apart from the surrounding corruption, creating new things where necessary, and to accomplish this, young and older men need to work together.

Is it time to “Tribe up,” as many young guys say online?

But paradoxically, a necessary step to “Tribing Up” (working collectively) involves cultivating many of the disciplined and moralistic habits most young people consider “Boomer”.

If you want a robust community, then you can only have it if you grind hard, build economic resources, commit to sacrifice, take one for the team, and start pulling on those bootstraps. Ironically, to escape the trap of modernity, young men need to embrace many of the old-fashioned platitudes that the mainstream cynically fed them as cover for stealing their inheritance. I guess it should come as no surprise that traditional wisdom generally works, but many of the Zoomer set are still having none of this old-fashioned advice.

Indeed, the young face a kind of paradoxical dilemma. Give in to Millennial do-gooderism and risk becoming the next iteration of naive wage slaves grinding their lives away to fuel the dying gasp of the Boomer Truth Regime, or follow the post-ironic realist despair of the Zoomer era and fall victim to the worst bad habits of the new underclasses, becoming a dependent client of a system that wants your destruction.

Really, it shouldn’t be any surprise that we are all talking past each other.

The Millennial right is trying to speak in the mode of disabused realism. The Zoomer right is looking for catharsis, which might render their regrettable situation emotionally meaningful. It’s a strange performative dance between two cohorts standing perilously on the same sinking ship.

In these circumstances, I find it hard not to think back to one classic scene, etched into the Xillennial imagination and now immortalized in memes: Artax's death in The Neverending Story.

As the scene unfolds within the film's broader plot, Atreyu and his horse, Artax, are tasked with saving their world, Fantasia, from imminent destruction by a mysterious, unstoppable force known as “The Nothing”. Trying to find a solution to the mysterious entity that consumes everything in its path, Atreyu and Artax search high and low throughout the land for an answer. After exploring every ordinary answer, the pair find themselves seeking the world’s most mysterious oracle, lost in the treacherous Swamps of Sadness, where all who despair sink endlessly into its waters. In these dark circumstances, Atreyu’s companion starts descending to his doom.

Watching Artax slowly sink into the Swamps of Sadness while the hero futilely implores him to keep hope is harrowing, especially for younger audiences. But I think the scene is also somewhat misunderstood. From the audience’s point of view, Artax’s death comes early in the plot, at the end of the first act. Arteyu’s adventures to this point have primarily occurred through exposition, and this is the first challenge the audience directly experiences. However, from Atreyu and Artax’s point of view, the Swamps of Saddness aren’t the beginning of the story but the end. The pair have already explored all corners of the world they know; there are no people left in Fantasia that can stop the nothing. The Swamps are a last-ditch effort, a “Hail Mary” pass to find some hope. And Artax, though he cannot physically speak, would be right to point out that there is no apparent reason to expect this time to be different. Everything has been tried, all solutions have been explored, nothing has worked, and from a rational, materialist point of view, there is no future.

Now that all worldly hope has departed, the only lifeline that remains is to find an unworldly sense of purpose. A hero must have a sense of ownership in his mission that endures even in the absence of the possibility of success. It doesn’t matter if the battle seems futile; he must fight on because of who he is and the other people who rely on him. In the despair of the Swamps of Saddness, Atreyu remembers this purpose and prevails. Artax forgets and is devoured by despondency.

Perhaps a too-cute life lesson from an ‘80s movie? But also a metaphor for what it feels like to speak across the generational divide in the post-discourse world of 2026.

At this point, it’s no secret that discourse, as we have known it, is dead. In fact, highlighting this reality every other week has become a recurring joke on this blog. In some sense, the observation is boring enough; we all agree that the internet has changed, and no one is making meaningful arguments to people in other communities. Likewise, most political arguments have been reduced to crude slop entertainment, less about persuading people of new ideas and more about validating them in their preconceptions.

Everyone acknowledges the problem, but no one ever seems to change their behavior. Somehow, people still think it means something to win the internet optics contest as if having the winning brand meant anything in an online world with no center other than the hyperparameters set into the algorithm during the last business cycle.

Even arguments, well-made arguments, aren’t nearly as relevant as we all pretend they are. For arguments to make a difference, we would all need to share a common society and culture that imposed meaningful moral consequences beyond raw power. Without that in place, the idea of “winning” some conversation is meaningless. You can expose government corruption, but there is no existing elite class to ensure that action is taken to prevent future abuses. You can detect subversion, but without real leaders that you trust, there is no opportunity to replace the bad actors with good men. People don’t have a natural ability to rally together and help themselves; no one has ever taught them how to act effectively.

Furthermore, simply decrying the situation, embracing cynicism, and chiding the normies for their slop consumption does nothing to fix the problem. Lecturing downtrodden people doesn’t cure them of their soul sickness; it just makes them more depressed and bitter. And chiding non-elite people for not having elite behaviors is not good leadership; it’s just more CYA, calling out the problem, framing it as someone else’s fault, and decrying the sorry state of things while those who look to you for leadership sink further into the swamp.

The purpose of any discourse in our post-discourse age is less to make an argument than to provide insight that points the way forward and inspires a sense of agency in an otherwise demoralized generation of young people. Certainly, there is a space for objective analysis and getting to the bottom of things, but any such analysis must eventually return to the imperative of purpose that allows people to find a reason to keep going, even if the objective facts in front of their eyes look bleak.

This is the only way to demonstrate leadership, and this is what we older Millennials need to provide to the younger men now looking to us for guidance.

What does providing this type of guidance look like?

Certainly, it begins with cultivating a deeper relationship with spirituality and transcendental purpose. But also in a more temporal sense, it means developing a common collective identity and becoming comfortable using language that expresses that implicit collective consciousness.

It might seem like a LARP to discuss something like collective consciousness in such an atomized age, but collective consciousness isn’t magic; it’s just what humans develop when they understand a common mission and shared future, and then work to support one another in their efforts.

Might something like this be brewing in 2026?

In terms of the recent revelations exposed by Jacob Savage, finding a sense of group identity feels like an imperative for white men. There is no future as an individual among a sea of enemies pursuing their collective group interests. Unite and survive, or die divided.

This is perhaps why, in my own way, I have had a marked change in how I understand nationalism and feelings of racial solidarity over the last decade. From the outset, I have been skeptical of such crude forms of nationalism as the approach often ignores the deeper problems of modernity. But then again, maybe this growing sense of solidarity, emerging in the wake of such overt discrimination against young white men, might be the beginning of something deeper that will allow us to overcome this age of total atomization.

As the ancients knew, a people without a polis has no future, and there is vitality to that sense of group loyalty, what Ibn Khaldun called “Asabiyyah”. Solidarity is not just petty tribalism, race against race, family against family, brother against brother. Solidarity is the seed of human nobility in its most organic form, loving kin as the first step towards a greater spiritual consciousness across the great chain of being.

The modern political right talks a lot about this kind of collective consciousness, but seems very far away from cultivating it. As I finish this essay, in the wake of recent months that have contained assassinations, political upheavals, and scandals that should have shaken any reasonable person to their core, the modern right cannot seem to find anything better to do than to infight over petty differences. In crisis, once more, CYA thinking takes over, and people practice politics by finding scapegoats, placing blame on their rivals, and trying to harness the chimp energy of the masses while simultaneously appearing above it all.

This is our contemporary understanding of political discourse, but it is the opposite of leadership and ownership over a communal spirit.

People, in possession of a true collective spirit, do not shatter under setbacks but rather pull together. They embody a sense of antifragility, a phalanx that fights as one, exhibiting greater unity as more pressure is applied. The group does not focus on blame, but on action. Disagreement is real, but divisions are ordered. Doubt is present, but solidarity is maintained. And all the while, people look towards a common future, a future to be shared collectively with one another and for their children.

Such a unified feeling is a spiritual quality. But also a natural one, as Kipling wrote, it is literally a law.

Now this is the Law of the Jungle — as old and as true as the sky;

And the Wolf that shall keep it may prosper, but the Wolf that shall break it must die.

As the creeper that girdles the tree-trunk the Law runneth forward and back —

For the strength of the Pack is the Wolf, and the strength of the Wolf is the Pack.

Many say that developing such an instinct in this state of liquid modernity is impossible. But I think it is possible. In fact, not just possible but essential.

And there are many challenges.

Developing this kind of organic collective consciousness involves solving many of the core riddles of modernity, finding a healthier relationship with technology, and rediscovering the folkways that once unified individuals across lines of gender and age. There will be many failures. However, without falling into uncharacteristic optimism, I think that we men of the early 21st century, hoodwinked and dispossessed though we are, are still equal to this task.

It is the mission that history has assigned to us. It is our generation's ultimate destiny.

![The Stages of Life (1835). Museum der Bildenden Künste, Leipzig. The Stages of Life is a meditation on the artist's mortality, depicting five ships at various distances. The foreground similarly shows five figures at different stages of life.[95] The Stages of Life (1835). Museum der Bildenden Künste, Leipzig. The Stages of Life is a meditation on the artist's mortality, depicting five ships at various distances. The foreground similarly shows five figures at different stages of life.[95]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!nsrh!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F7cccfb31-d31e-440e-9331-5a0c2323dd15_1280x994.jpeg)

Old Gen Y here.

Only made it in my career (university prof) because of a single repentant boomer gave me a chance.

Now trying my best to support younger men in my community. We must do better than the boomers.

The Boomers and older Gen Xers running Hollywood writing rooms in Savage's piece won't be there forever. Meanwhile, Netflix is buying Warners and the movie business may not support the local cinema. Change is around the corner and who knows what it looks like. It's not a solution for the dispossessed white man seeking career advancement and satisfaction today or tomorrow, but the system that ignored them is unsustainable.

I see a similar dysfunctional business model in the Magisterium playing out. The Boomer cardinals (and Francis during his pontificate) have certain goals for the Church that will be washed away when the younger, more trad priests take their place in the hierarchy. It's a matter of time.