Ghosts in the Shadow of the Mouse

You can't go home again, but you can never really leave it.

We cross the San Fernando Valley in the late afternoon, just as the sun begins to set over Los Angeles. It has been a six-hour ride with nothing much to see, and everyone is ready for a break. My wife wants to see the Hollywood sign, but we don’t have time to take a detour, so instead, we pull off the road to stretch our legs and take in the scenery between a gas station and a bodega, looking out on the city.

“This place is strange,” my wife says. “It feels like San Francisco but more so.”

L.A. does feel strange. And it’s not just the city. The land around us seems unsettling like an alien spiritual force is, somehow, indelibly baked into the earth and architecture.

I have often fancied that the Western part of North America has a strange “memory-less” quality. History happens here, to be sure, but it is never remembered. People come and go, but the landscape does not recall their passing. I notice this feeling most of all in Southern California. There is an unmistakable sense of desolation, even in one of the largest cities on the continent.

The feeling hangs in how the wind moves and doesn’t. Mornings in Los Angeles have an unusual brightness that carries over into the night as a strange glow, blurring the transition between the days. The seasons of the year never feel distinct, and the city never seems to have permanent places, just temporary scenes that are set up to serve a purpose and then, perhaps, torn down when not in use. In fact, the entire city feels like it might have just come into existence yesterday, risen out of the desert, and formed from sand, seawater, and media hype.

No one captured this LA feeling better than the late David Lynch, immortalized in his masterpiece Mulholland Drive, where Hollywood appears as a graveyard of amnesiacs and celluloid Ghosts, ruled over by malignant entities.

A lot of visitors say that Los Angeles feels fake. But the spirit here is real; it is just a deeply alienating spirit. And breathing in the air somewhere on North Mission Street, I am struck with a sense that this place could never really feel like home, no matter how long I stayed here.

Eventually, my wife gestures to my son, who is nodding off. It is still a long way to our hotel, and there is quite a bit of driving. LA is a strange place, but it is not our final destination. Instead, this Thanksgiving holiday, our final destination is Disneyland.

Disneyland is a difficult phenomenon to explain, even though, on the surface, it doesn't really need an explanation. After all, Disneyland is the world's most famous amusement park and an iconic part of 20th-century Americana, up there with brands like McDonald’s and Coca-Cola.

On paper, Disneyland doesn’t seem like it should be a big deal. The park is now almost 70 years old and the original Anaheim theme park looks like a relic in comparison to its more recent rivals. Truth be told, Disneyland mainly sells memorabilia and rides, and the rides aren’t even that good. But people love Disneyland and are willing to pay its very, very inflated price tag year after year.

The price tag is ordinarily much more than my family would be willing to pay. And I find it hard to forget that the main reason why my extended family is here at all is to avoid a more traditional celebration of Thanksgiving without my father, whose recent passing is still a fresh and painful memory. Many people tell me that avoiding the experience of loss rather than confronting it is a distinct stereotype of Americans generally, and Californians in particular. But it is hard for me to otherwise imagine celebrating Thanksgiving with my father so recently absent. The vacation (financed by older relatives) seems like a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to show my son the “Disney Experience,” which I remember when a trip here was much cheaper.

Disneyland is the high-water mark of L.A. unreality. It is a simulacrum of wholesome functionality that would make Catherine the Great’s ministers blush. The park has a bubble around it for blocks where none of the ordinary vagrancy or crime problems that infest the rest of the city seem to exist. Even the entrance gate and security check seem less sordid than most; even the people in line are nice, to the point where when I accidentally run over someone’s foot with a carriage, all I get is an understanding smile and eye-roll.

The entrance to the park does not disappoint. After we get through the ticket check and walk past the flower collage of Mickey Mouse, we arrive at “Mainstreet U.S.A,” which resembles a small European town square, a literal Potemkin village of shops that look like places people might actually live. From Mainstreet, we follow the road to the central pavilion built around an iconic statue of Mickey, hand-in-hand with Walt himself in front of the backdrop of the famous Disneyland castle. As artificial as I know it all is, the experience nevertheless seems magical, even on my third time around.

“How do they keep this place so clean?” why wife asks, amazed.

She is right. There isn't a speck of garbage anywhere in the entire park, not a chip of paint, not a single patch of refuse or spilled concession. It’s immaculate, giving a visitor the feeling that the park was built yesterday and that nothing could go wrong.

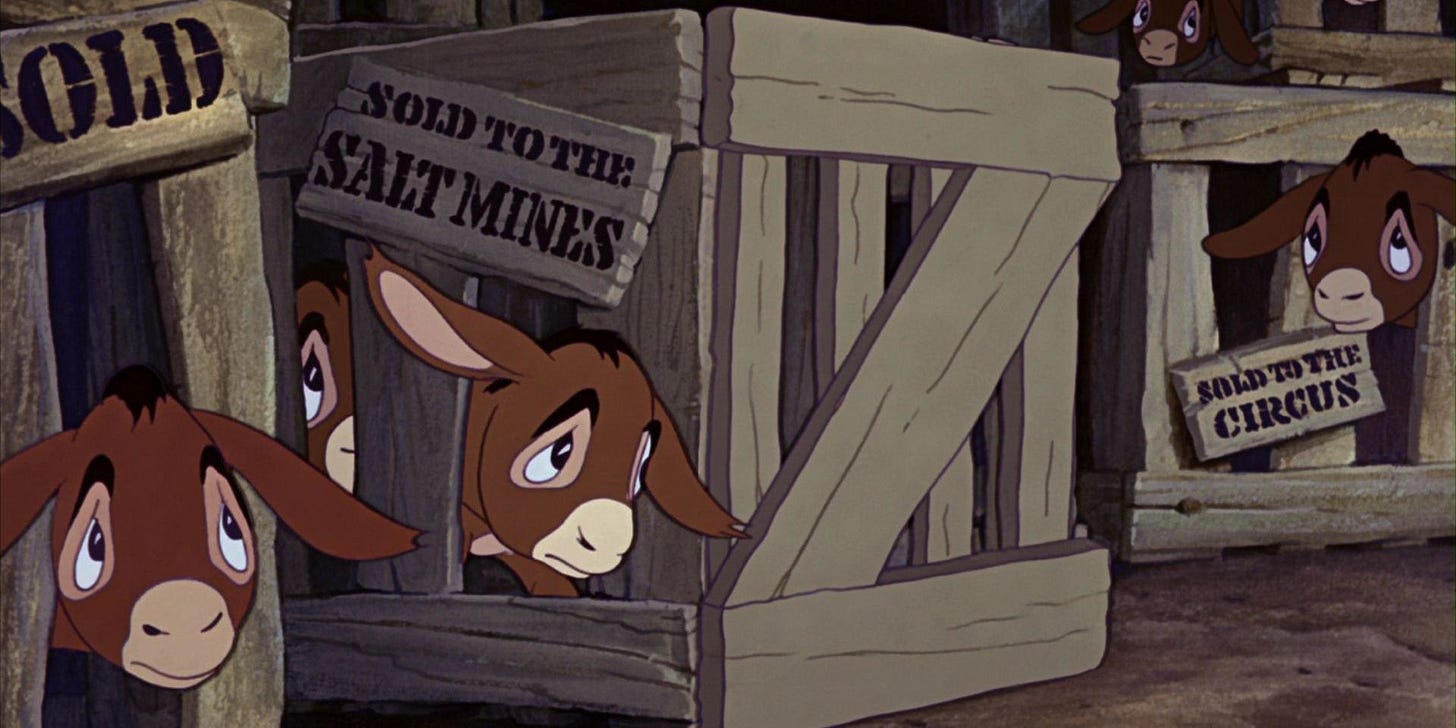

Well, some things go wrong because on the first ride my son and I get on, “Pinochio’s Daring Adventure”, breaks down halfway through. Having never seen the original 1940 film, my son is enjoying the sights and sounds until the car unceremoniously grinds to a halt right in the middle of the “Pleasure Island” portion of the story. The irony does lie a little thick in the air, first being stuck in an amusement park inside of an amusement park and then having to walk past halted-animatronic children being transformed into donkeys to reach the entrance.

I certainly wouldn't be the only person who felt the “Pleasure Island” scene from Pinocchio to be one of the most emotionally rattling scenes ever animated. Our hero, Pinocchio, the living puppet, is tempted away from his school by a Coachman who promises him a vacation in Pleasure Island. In this place, children live with no responsibilities and indulge in every urge, from consumption and indolence to alcohol and violence. At first, the puppet earnestly accepts the Coachman’s offer at face value, pursuing a life of hedonism with his friends until he discovers the dark truth that they are, one by one, being transformed into donkeys.

In one particularly horrifying scene, the film depicts the final fate of the boys who stayed too long in Pleasure Island, who are fully transformed into animals, stripped of their clothes by the coachman and his demonic henchman, and crated up to work in the Salt mines. As the henchmen proceed, one of the boys, still not fully de-humanized cries his name and pleads for his mother, only to be brutally chastised by the Coachman who throws him into the corner with the others and yells at the cowering creatures:

"You boys had your fun! Now it's time to pay for it!"

To this day, I can't enter an amusement park without thinking of Pinocchio’s Pleasure Island scene. Years later, I was surprised to find that though the Pleasure Island does appear in Carlo Collodi's original Adventures of Pinocchio, it felt distinctly less horrifying. Collodi's story of the living puppet was brutal but existed in a kind of surreal fairytale aesthetic that made the specific bad events happening feel detached. In typical form, Walt Disney emphasized the intensely personal quality of the tale and the horrific reality of a child being robbed of his innocence, and the scene is subsequently an immortal piece of cinema history.

Walt Disney’s vision of Pleasure Island is nothing short of harrowing, but it also contains a note of irony. The man who built America’s perfect theme park was also the man who gave most Americans their most traumatic childhood memories of such places.

Sure enough, Walt Disney did have a love-hate relationship with amusement parks, which, in his time, were little more than permanent carnivals. At once, the scene of early 20th-century theme parks was vital and exhilarating. It was a place where life seemed to burn strongest. But then there was the seedier side of the endeavor. There was the filth and rubbish that one could see once the bright lights dimmed. There were the strange low-life "carnies" who ran the productions, oftentimes supporting alcohol and drug habits on the side. But most of all, the problem with amusement parks was that ever-present feeling of indulgence, the puritanical fear that behind the festivities, more nefarious forces were lurking, ready to punish you for pursuing pleasure for its own sake in the “Devil’s Playground.”

However, Walt Disney would fix all of these problems in his own theme park.

"Disneyland" is as far away from Pleasure Island as humanly possible. Nothing about Disneyland is seedy. Its streets are pristine. Its employees (which it calls "cast members") are more like aspiring movie stars than blue-collar workers and wear oddly sincere smiles on their faces at all times. Even Disneyland’s rides have a strange wholesomeness to them.

When you pay the exorbitant price tag and experience the various amusements, you aren't "indulging your base desire for pleasure". You are “exploring" and "creating memories." Disneyland is not a "Devil's Playground”. The Prince of Darkness and his Coachman have been evicted from this land, defeated by America's most wholesome champion: Mickey Mouse.

Disneyland doesn't sell pleasure. It sells dreams. It sells inspiring tales about past heroism and aspirational visions of a future we all might hope for. The park is a still frame of the optimism of America circa 1955 as Disney imagined it. It is a testament to America’s Faustian spirit. Each one of its various sections tells that story.

Frontier Land and Adventure Land are tributes to the brave spirit of exploration that conquered America and the world, respectively. Fantasy Land was a tribute to the common heroic mythology that constituted the nation’s more ethnic heritage, showcasing Disney’s version of European fairy tales loomed over by the notably alpine “Matterhorn.” Last but not least, there is Tomorrow Land, Disney’s vision of the future, the dream of how American optimism was going to conquer the stars themselves. Perhaps it's looking somewhat dated now, but the rides weren't just simulations of spaceships. They were a story of the greatness waiting in store for all Americans when we might reach higher and go further than any human ever had.

Even the park's most mocked ride, It's a Small World After All, is just Walt Disney’s own hope for multi-cultural world peace. People laugh because it’s just a bunch of dancing animatronic dolls, but it’s still more inspiring than anything you see from our modern globalist leaders working towards the same vision.

Disneyland isn't just a good time. It’s Utopian. It’s religious. It shows people things that they SHOULD want. Disneyland doesn’t have tourists; it has pilgrims. Pilgrims who have come here to worship that last scrap of Americana that people still believe in. And maybe by believing and wanting these things badly enough, people can collectively become one with the American spirit as Walt Disney imagined it. That might sound like a cult, but it's the happiest cult on earth.

And it’s hard not to be happy at Disneyland. After our family tries out a few more very enjoyable rides, from Pirates of the Caribbean to Jungle Cruise to The Underwater Adventure, we return to the central plaza to take a break under the statue of Walt and Mickey hand-in-hand.

It might be my own pop-culture-addled Millennial brain, but looking at the statue of Walt and Mickey, I can’t help but think back to the video game Bioshock where a similar bronze statue of an American industrialist, Andrew Ryan, stands astride the entrance to his Utopia bearing the words "NO GODS OR KINGS. ONLY MAN".

Like Walt Disney, Bioshock’s Andrew Ryan also built a city where his ideal version of America could be experienced indefinitely, this one at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean. Still, Ryan’s dream of a society of heroic individuals was undone by its very realization. The technology that was supposed to uplift his followers into a genetic master race instead transformed them into spiritual slaves, preying on the weak in the name of petty vanity. Ryan’s vision of a brave new Prometheus was devoured by its dark parody: the egotistical “Splicers” who remained little more than heroin addicts with superhuman powers.

Do all utopias end up being devoured by their own dark doppelgangers?

Disneyland seems to be suffering from just such a fate, slowly being consumed by its perverse simulacrum. Even with the meticulously managed park design and rides, one can see the vision of Walt Disney fall under the shadow of the mouse. The hopes that the dreams were meant to inspire are forgotten within the mist of the dream itself.

Everything looks just as it was built yesterday, but it’s not the same park that I remember from the 1990s.

Of course, there are the small things. In 2024, the markers of DEI values and trans pride are everywhere. The propaganda is probably less prominent than even a year ago, but it is still a reminder of how deeply the symbol of American wholesomeness participated in its very own version of “Pleasure Island”, with children robbed of their innocence and mutilated in its wake.

Still, gender-cult aside, a more notable thing about Disneyland in 2024 is how the tourists themselves have changed. About half of the visitors are the people you would ordinarily expect: the families, the school groups, and the adults celebrating a special occasion. But then there are the infamous “Disney adults” who have defined their lives around Disney products and spend a significant portion of their income on visiting the theme park periodically.

You’d think it would be impossible to notice these people in a crowd of hundreds, but something indescribable stands out about them. In some sense, these were the people Disneyland actually created, not aspirational heroes but consumers. They are the people who define themselves not by the essence of the dream that Disney wanted people to believe in but in the form of the products themselves and nostalgic limerence. Somehow, you can never really escape Pleasure Island, and these people stick out as clearly as if they were wearing donkey ears.

But no one can really escape the Baudrillarian trap of Disneyland, even if they are experiencing its attractions as an ordinary parent and not a Disney adult. People no longer see the “dreams” as references to the real world or the original folk tales. Instead, each attraction is an allusion to a Disney IP and consumer product. The Underwater Adventure is now a reference to Finding Nemo, while “Jungle Cruise” and “Pirates of the Caribbean” are major film franchises. We aren’t exploring Walt’s romantic vision of the world and its future, but just fixtures of our own nostalgia.

I find Disneyland’s nostalgia overpowering. And walking about the park, I find myself dwelling on my father’s absence more than ever before. The feeling of loss even gets to the point where I find myself questioning how organic my experience with my son really is.

When my father and I visited “Tom Sawyer’s Island,” “The Old West Shooting Range,” or “The Matterhorn” in the 1990s, they contained a sense of novelty. These weren’t just rides but doors that opened into a larger world. “Tom Sawyer’s Island” was actually a window into the world of Mark Twain. The shooting range was a chance to experience the Wild West stories that my father enjoyed reading about as a child in Austria. The Matterhorn might seem like just a ride, but much more so, it was an opportunity to hear stories about the real Matterhorn in Switzerland that many men had died trying to climb.

In contrast, my own trip to Disney with my son feels much more like an effort to chase my own childhood memories and visit the same rides that I had enjoyed. I want to make sure that I am giving my son the experience that my father gave me. It is a sincere expression but also a desire that couldn’t really be fulfilled. The quest to scratch the itch of nostalgia is futile. Isn’t that why it hurts so much?

A man cannot step in the same river twice, for it is not the same river, and he is not the same man.

But the experience at Disneyland is not bad at all. The park is fun, and the joys with my son and the rest of the extended family are real enough. Everyone has a good time and wants to come back while I try not to think about the price. Still, it doesn’t feel like I found what I was looking for.

Was I looking for a real dream about the future?

But there aren’t any more real dreams in Disneyland; there are just shadows and memories.

I have found my thoughts returning to Disneyland and Southern California once again in the early days of 2025, as fire rages through the Los Angeles hills, where my latest journey there began. The hills seemed sinister enough when they were beautifully illuminated by the setting sun. To see them now in flames feels outright infernal. California residents are in shock, but this disaster has been coming for a long time.

The Golden State’s crumbling infrastructure was a widely known problem, as was its declining ability to continue safe forest management and fight wildfires. Much less discussed was the total corruption of the Californian political class and its subsequently insane policies that left the broader questions of water management, crime, and vagrancy unaddressed while nevertheless draining billions from the budget to pay for flashy progressive boondoggles.

Inevitably, the Californian ruling class presented the fires as an unpredictable and unavoidable act of God, just part and parcel of living in a waterless desert where humans were never meant to be. But the cataclysm couldn’t have been more predictable. The disaster had been foreseen by every clear-eyed thinker familiar with the state. Moreover, all elements of California’s dysfunction seemed to have a hand in its origin, meeting together like a perfect storm prophesized by every news item in recent California history and quite a few of its films.

One film about California I can’t help but think back to in the wake of the recent fires is Roman Polanski’s 1971 masterpiece, Chinatown. Strangely enough, all the roots of California’s modern crisis seem to lurk in the background of this film’s strangely paced plot: the fights over water usage, government dysfunction, and a politically (and sexually) corrupted ruling class. It’s never clear what the connection is between these themes, save from what can be gleaned from the movie’s cryptic dialogue.

For instance, what is the link between my native state’s inability to manage water and the incredible perversity of its ruling oligarchy?

I was never able to put the pieces together, but I am pretty sure that it has something to do with this famous exchange in Polanski’s classic film:

Jake Gittes: How much are you worth?

Noah Cross: I have no idea. How much do you want?

Jake: I just wanna know what you're worth. More than 10 million?

Noah: Oh my, yes!

Jake: Why are you doing it? How much better can you eat? What could you buy that you can't already afford?

Noah: The future, Mr. Gittes! The future.

The emphasis on “the future” by Mr. Cross here is supremely ironic insofar as his primary desire is the custody of a child produced by his incestuous relationship with his own daughter. The future that Noah Cross imagines is not the cultivation of a better world that will exist after his passing but rather the pillaging and monopolization of other people’s lives just so he can live out a tyrannical aristocratic fantasy while his homeland and real family fall into ruin.

It is a simulacrum of monarchy rather than a real one. It is the desire to create a place where meaning isn’t earned but is bought, and the function of love and even truth is transferred over to an automatic process of industry.

And isn’t that desire for building artificial human connection the thread that links every scion of the Golden State?

It is a story that Hollywood is certainly fond of retelling when it looks at its own history, from Chinatown, to There Will Be Blood, to Citizen Cane whose real world inspiration, William Randolph Hearst, gave California its only European-style castle but without a European-style Aristocracy to rule it.

Everyone comes to this state to produce that same thing: a simulated Utopia, a celluloid love, a Mechanical Monarchy that will solve everyone’s problems, isolate the passion of humanity, and iterate endlessly into the future while never having to acknowledge the humanity of the people that it serves, nor the sacredness of land which they occupy.

But the artificial dream never works, because the men who create it always walk into the same trap. They begin to believe their own lies. They get high on their own supply. They fall in love with their own simulation and forget what keeps it all in motion.

Wouldn’t it have been better had the leaders of California taken ownership over the state’s real land and people rather than being absorbed into their beautiful fantasies?

I think back to the statue of Walt Disney and Mickey Mouse sitting in the central plaza of Disneyland. It looks like a King leading his heir. Walt was a man with a real vision, and in a different age, Disney might have been a king, showing the people of California his ideals, not through entertainment, but in the actual lives of their communities. Instead, the state welcomed him as a brilliant innovator, but California didn’t need another innovator; it needed a father figure.

This strange contradiction seems relevant more than ever today, as I hear many right-leaning Californians talk about what comes after the fire. Certainly, while the catastrophe is tragic, its timing is somewhat fortuitous. The fire will no doubt shake the California leadership class to its core, and with the rest of the country taking a turn back to sanity, might this not be the ideal time for reform? Could this be the ideal time to build back better and finally get a reasonable approach to governing that could return the state to its glory day?

But for me these hopes are all still very surface level. Because the core problems of the state are well beyond simple reform.

California doesn’t need different government policies. It doesn’t even need a different ruling class, though that would be nice. California needs a new spiritual understanding of itself as a place, and as a home for people. California needs to believe that it is a land where good things last and deep things might flourish in the long term, given the time they need to thrive organically. California needs to be the place for real life to grow and not a graveyard housing aging megalomaniacs and the ghosts of their artificial dreams.

In other words, California is confronting the real riddle of modernity. We all know what we have lost in terms of sincerity in terms of organic connection to place. But we can’t see the way back, at least not by means that have been offered to us.

Regardless of political persuasion, every Millennial has struggled unsuccessfully with this problem of belonging and discovering an authentic human life and home. Beyond our declining generational wealth and stifling political situation, we all looked at our lives and found just this thing missing. The real problem was not just that we were poorer and afforded less status than previous generations, but that we had no place in history, no place to call home and that we would be soon forgotten by all those who came after us, a penultimate note of futility in a system locked into perpetual decline.

Yet every lifeline that we tried to grasp seemed to fall through. We tried to find the “new sincerity” talked about by those like David Foster Wallace, but then saw it descend in to snark and online profilicity. We tried to get change through politics and unleashed more vindictive bitterness than realistic change. We restored to finding that lost contentedness online, only to see that ambition bleed into ephemeral false dreams and seductions that kept us all satiated and simulated, all the while we were losing our humanity part by part.

We all want to escape from the trap of Pleasure Island. We all want to go home. Even if we don’t exactly know what a “home” means in the modern world. At least we know what it isn’t.

For some time, I have been thinking about what it means for a people to own a land such that they are truly of that place and that place is characterized by their presence. As modern society reaches the limits of de-territorialized individualism, so many modern problems come down to what it means to have a deep identity and a connection to the earth. Still, producing that connection is challenging.

When you look at the issue anthropologically, the task at hand looks clear enough. Peoplehood (and subsequently nationhood) is based on an experience of a covenant where a collective of people bind themselves to a place and a set of spiritual practices in service to a shared concept of Divinity. It’s the same pattern that plays over again in history and what people sometimes call “ethnogenesis.” But given how separated we are from real spiritual leadership and collective organization, it isn’t even very clear how such an event could exist in the modern world, even though it seems like it must happen again for there to be any future worth believing in.

A nation always begins with a set of men who have the inclination to build etched into their being, the movers, the shakers, what Carlyle might call “great men.” Still, it requires more than greatness. The fathers of new nations cannot hold their vanity as the end of their ambition. They cannot be chiefly concerned with erecting idols dedicated to their pleasure, muses, or personal fascination. Rather, there must be a sacrifice, an ego death on the part of the founders themselves, to sublimate their wills to the land and the collective and to pass its wealth down to posterity. Always, there must exist a desire to pour forth one’s own blood for an unseen future, to sublimate one’s will to a higher power, and to commit one’s bones to the earth with the hope and conviction that something greater will be brought forward.

I find this understanding challenging, having no great pretensions to be such a mover and shaker myself. Still, it seems that I have to start somewhere, following the forms of those who have gone before me, returning to the land that defined my childhood, and seeing what can be done with what is left over.

California is no longer the place that I remember growing up. It’s more chaotic, more short-sighted, more corporate, and more soulless. By the time I had my own family, the state was a place that was so concerned about ‘the future”; it seemed not to care about its actual children and the land that would be left over when the current fads passed away.

California was not a hard place to leave. And by the time I left it, I truly hated what it had become. Yet, I don’t know if someone can ever really leave the place that formed them. And I suppose that’s as good a definition of “home” as any.

Home is the place that you can’t leave behind.

The spirit of the age screams: “Let the dead bury the dead”. But I don’t think the Golden State is dead quite yet. Where there is hope, there is life. And hope was always the hallmark of California.

Hope for the future was what drew my earliest Californian ancestors across the plains to settle in the late 19th century. Then, once more, hope drew the rest of my mother’s family to the state in the mid-20th century when the economic prospects in the West looked more promising.

And my father’s story was much the same. Growing up in Europe, he dreamed of the promises of California, and his early life comprised one long journey west away from the confining bonds of the old world to the liberation of the new, from eastern Europe to Austria, from Austria to Quebec, from Quebec to the Midwest, and finally to California.

My father loved California. And, during the last decades of the 20th century, the place seemed to embody something of his philosophy as a lifelong classical liberal and dreamer about human potential. It is strange to find myself now, thinking in the exact opposite direction, looking back to the same land as being a source of the very rootedness that my father was trying to escape coming here.

But it is just a different age.

In the last year of his life, my father spoke passionately about the prospect of buying land in the country for the family to hold collectively and to pass down to his grandchildren. Perhaps his fixation with land ownership was just fanciful. But for whatever reason, this new perspective seemed profound. It was as if my father had realized in his later years that the age of liberty was setting, and a new time was on the horizon. The season for exploration and expansion had passed; now is a season for digging deep and planting roots.

I feel this change too, even more now, witnessing the state’s recent disasters and haunted by the creeping anxiety that I won’t be able to give my son the same comforting world that my parents gave to me. Things feel more hostile in this new world, and things might get worse yet. And I have become similarly convinced that we need to look for different types of wealth for our children that might help them in the future.

Perhaps we might leave them a more grounded human life or connections to real people and places not built on fantasy and illusion. Perhaps we might bequeath them a land with a history that they are connected to, and the more solid identity that goes along with that. Perhaps we might leave them a better capacity to think and act collectively.

New beginnings have to start somewhere. Memories must be built. A sense of a community needs to be forged, not by abstract philosophical arguments, but by people dedicating their lives to a future world they will never see. And that future world cannot be kept waiting. The yoke of the new life must be taken up today, even by men like myself, who are still deeply scarred by modernity. The foundations of a different place must be physically built into the earth itself, even if it is in a land that never could remember anything.

Never been to California, but I always get a sense from others that it’s deepest problems come from the fact that it was a land where restless runners got stuck in; Once you can no longer go any further west, sooner or later, whatever was chasing you catches up.

And whatever existed before can’t stand your curse quietly neither.

This essay is especially poignant I& one considers California’s role as a bellwether state. As we run out of physical frontiers to exploit, and ruling classes squander their latitude to manipulate currencies and financial systems, it becomes important to think of ways to preserve value and build a future for those important to us.